This CIA mole made MILLIONS of DOLLARS spying for the Soviets

In late 1986, it became apparent to anyone in Langley that the CIA was on the verge of a catastrophe. For years preceding the fateful moment, the Soviet KGB had been suspiciously successful in identifying, arresting and executing double agents recruited by the agency in the USSR. The uncomfortable truth was that the CIA had a mole within its ranks. When it became apparent, the manhunt for one of the most destructive and highest paid spies in American history began.

Deadly trap

In 1985, Oleg Gordievsky, acting head of the KGB cell in London, received a panicked telegram from Moscow. He was ordered to return to the Soviet capital. Being a double agent working for MI6, Gordievsky had his reasons to disobey. However, he decided to take the risk of returning to Moscow, where he was later drugged and interrogated.

Double agent Oleg Gordievsky.

Double agent Oleg Gordievsky.

This was a time when the CIA was losing assets to the KGB, one by one. High profile figures in Soviet security agencies and scientific institutions were handpicked by the KGB counterintelligence with terrifying ease. Death awaited those who were caught spying for the U.S.

By 1990, the CIA virtually stopped recruiting new double agents in the USSR, because the list of its acting agents was vanishing like sand through fingers. Unless the leak was identified, the CIA had no means to protect its assets in the USSR.

The mole hunt

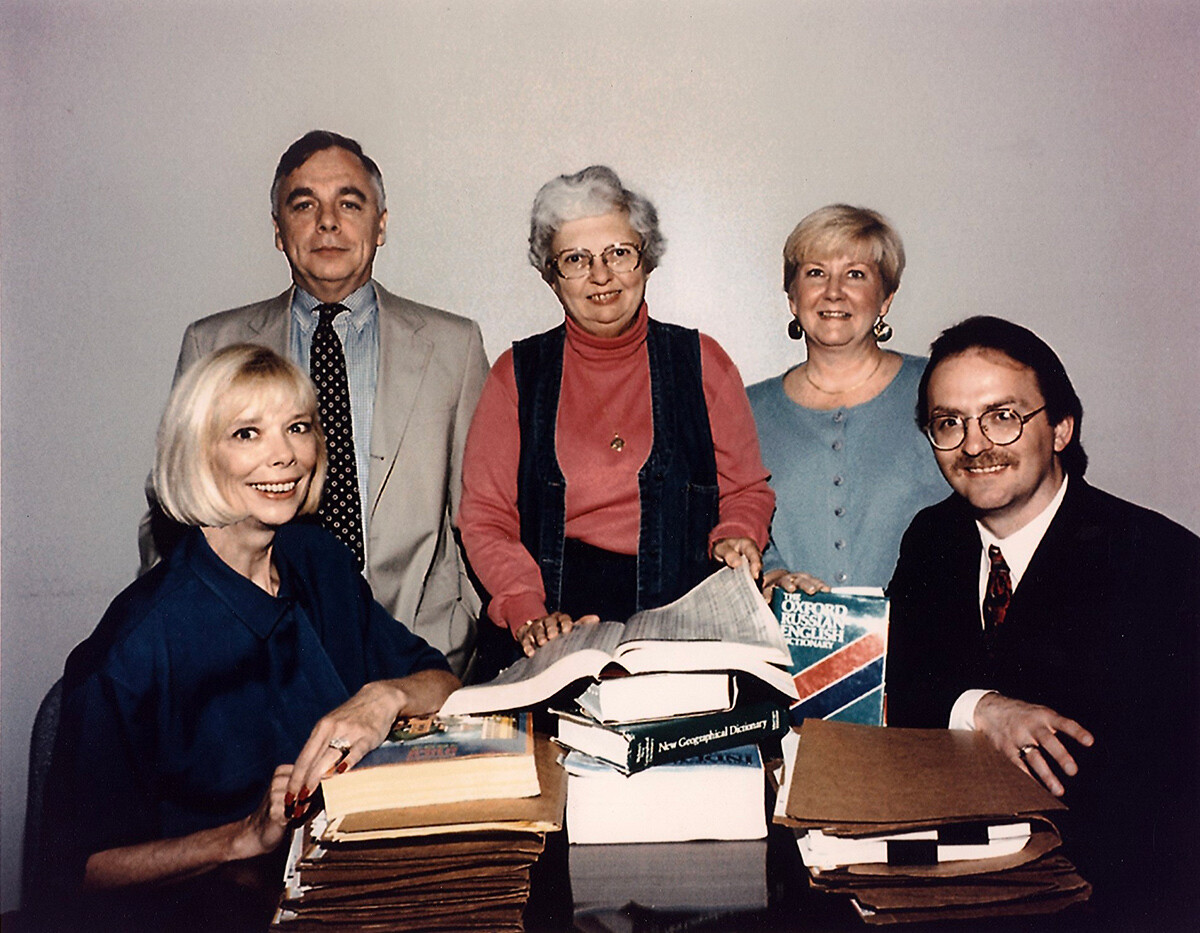

Desperate to find the culprit, the CIA assembled a mole hunt team consisting of veteran CIA employees. Consisting of three gray haired women and two men, the team looked nothing like the spy hunters portrayed in movies, but it had all the means and expertise to uncover the origin of the deadly leaks that plagued the agency.

The CIA male hunt team. From left to right: Sandy Grimes, Paul Redmond, Jeanne Vertefeuille, Diana Worthen, Dan Payne.

The CIA male hunt team. From left to right: Sandy Grimes, Paul Redmond, Jeanne Vertefeuille, Diana Worthen, Dan Payne.

Although it was possible that the KGB had obtained access to the CIA documents or communications through bugs, the mole theory made the most sense.

In the course of their investigation, the mole hunt team was diverted from the right course multiple times. At first, the KGB ran a misinformation operation, which led the team to believe the mole was stationed at Warrenton Training Center, a classified CIA communications facility in Virginia. The mole hunters investigated over 90 people stationed at the facility, without definitive results.

The team came by the next red herring, when a source volunteered information that the KGB had penetrated the CIA with a mole who was born in the USSR. None of these was true, allowing the evasive mole to operate unpunished.

Soon, the mole hunt team comprised a list of all people who had access to the information that had been revealed to the Soviets. “We knew which people had the best access. So, we were able to weed down the list by the level of access the person had in addition to other considerations,” said member of the team Jeanne Vertefeuille.

Eventually, the list was reduced to 28 people. If there was a mole in the CIA, he or she was on the list.

The team began making the suspects take polygraph tests. One of the examined employees was CIA officer employed in the CIA’s Soviet/East Europe Division Aldrich Ames. He successfully passed the polygraph test twice.

A devastating divorce

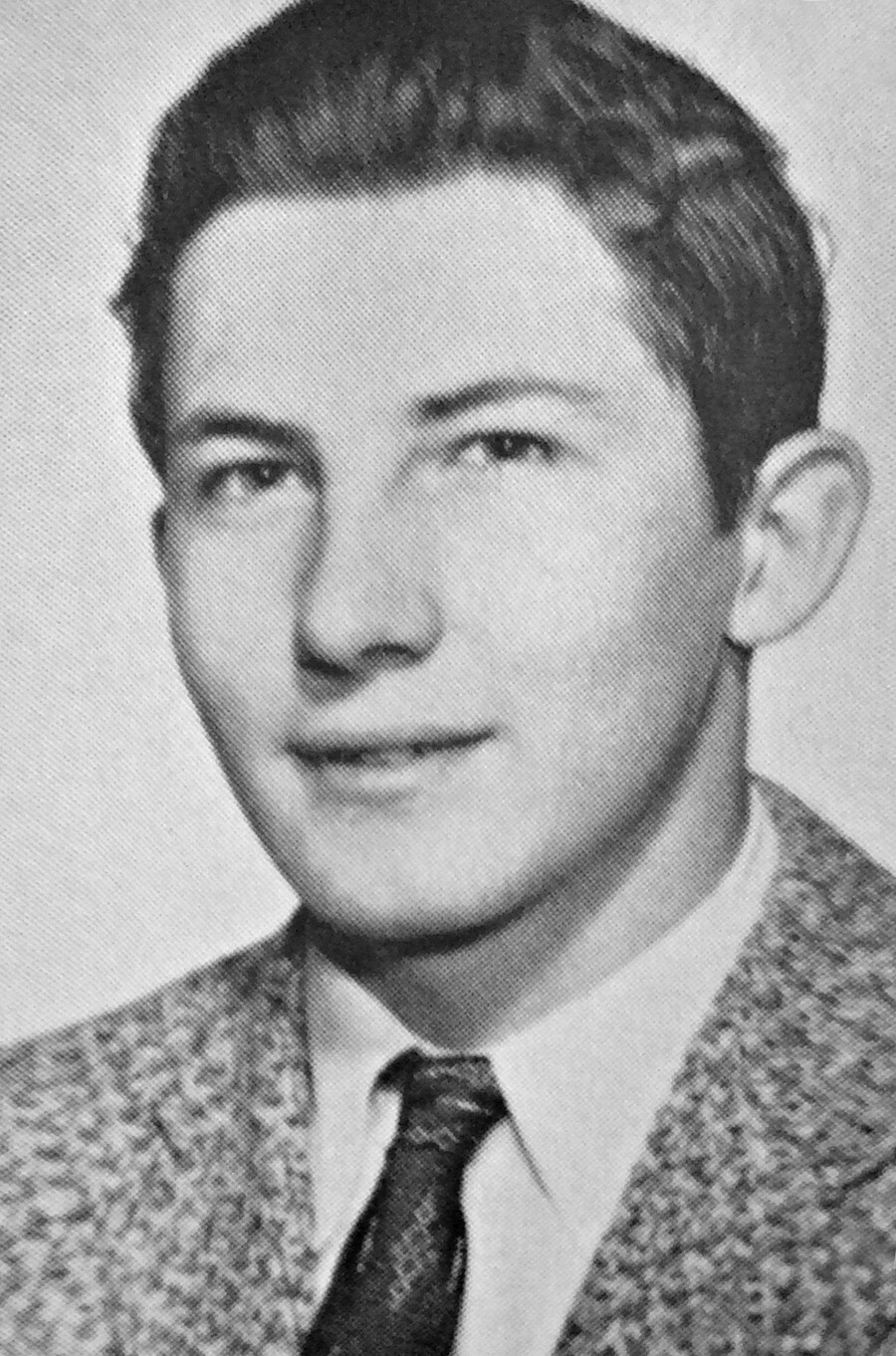

Aldrich Ames started career in the CIA in 1962. He married a fellow officer Nancy Segebarth, who subsequently resigned to abide by the CIA rule that prohibited spouses from working from the same office.

A young Aldrich Ames in the 1958 McLean High School yearbook.

A young Aldrich Ames in the 1958 McLean High School yearbook.

Ames was regularly rewarded for his service and promoted within the CIA ranks. By 1969, Ames had been promoted to case officer and sent to Ankara, Turkey, for his first assignment abroad. His job there was to target Soviet intelligence workers for CIA recruitment.

However, troubles were brewing behind the facade of the valuable and reliable employee. What nobody knew was that Ames’ marriage was going downhill. In addition, Ames was seen abusing alcohol on multiple occasions and participating in alcohol-infused incidents. He also had a tendency to procrastinate in submissions of financial documentation. However, all the mishaps were put under the rug.

In 1981, Ames was posted in Mexico City, while his wife remained in the U.S. In Mexico, Ames began an affair with a cultural attache in the Colombian embassy named María del Rosario Casas Dupuy, who was also a CIA informant handled by Ames.

Maria del Rosario Casas Ames, wife of senior Central Intelligence Agency Agent Aldrich Hazen Ames, gets in a car in front of a U.S. Federal Courthouse in Alexandria, VA.

Maria del Rosario Casas Ames, wife of senior Central Intelligence Agency Agent Aldrich Hazen Ames, gets in a car in front of a U.S. Federal Courthouse in Alexandria, VA.

Separation from his wife, coupled with a new relationship with a woman who was a heavy spender, put Ames in a difficult financial position. As part of the settlement with his ex wife, Ames agreed to pay debts the couple had accumulated, as well as to provide Nancy financial support for three and a half years, totalling some $46,000. Fearing the divorce – and the habits of his new passion – may bankrupt him, Ames offered his service to the KGB.

The million dollar spy

On April 16, 1985, Ames walked into the Soviet Embassy in Washington and offered the agency’s secrets to the KGB for sale. Fortunately for Ames, he was then assigned back to the CIA’s Soviet/East Europe Division, a posting that entitled him to have access to all active cases and plans of the CIA penetration of the KGB and Soviet military intelligence. For the Soviet KGB, it was a golden opportunity and they were willing to pay accordingly.

“Here are some press releases that I think you will find interesting,” said Ames’ Soviet handler when they first met. After the meeting, Ames drove to a remote park and looked inside the bag. There were $100 bills wrapped tightly. He counted $50,000 in total.

At first, Ames volunteered some information that he believed did not have any value and, thus, could not hurt U.S. interests. Yet, as the line was crossed, there was no going back. Ames was on the KGB’s generous, albeit tainted hook.

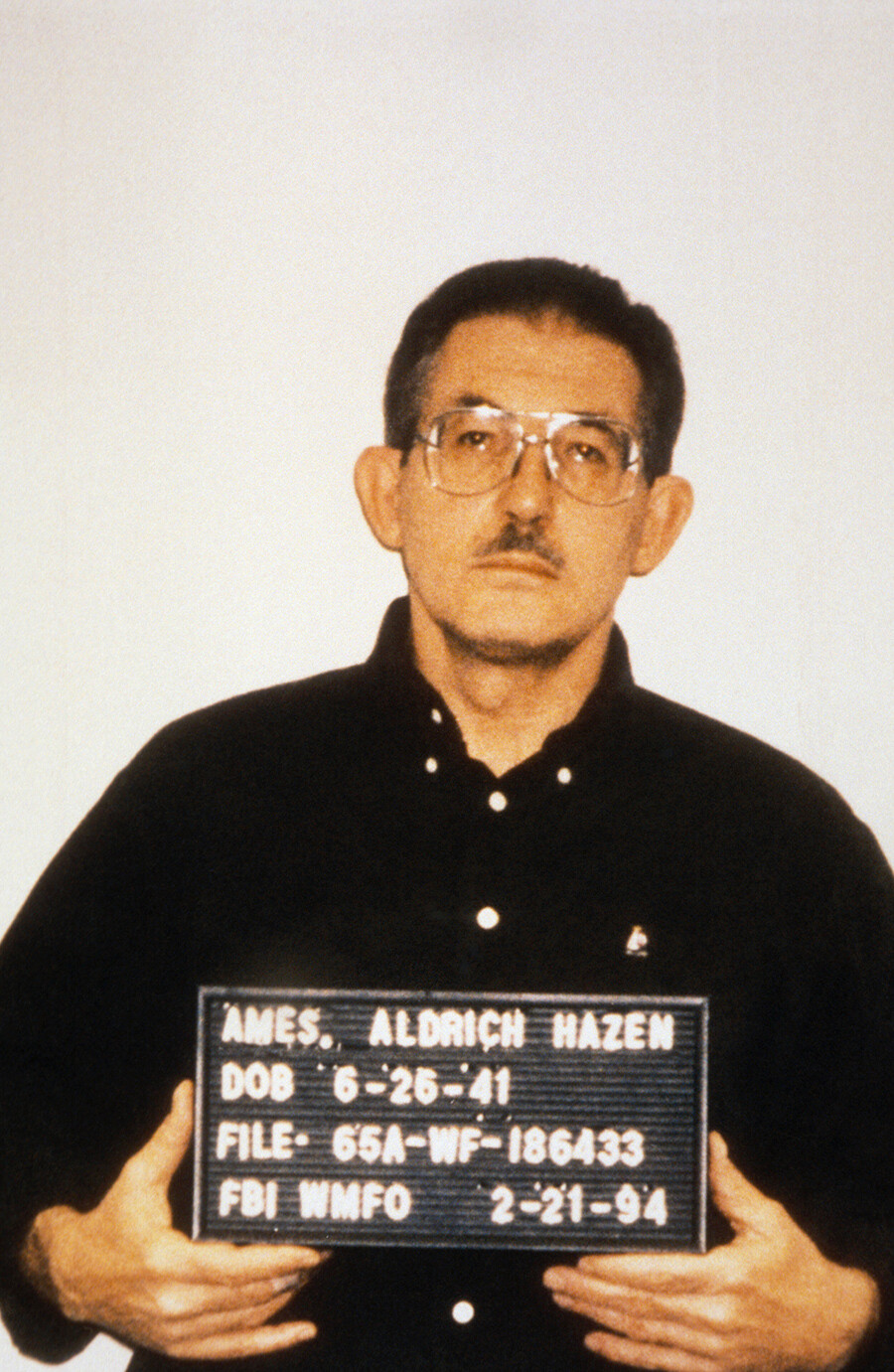

Aldrich Hazen Ames; former CIA officer convicted of espionage.

Aldrich Hazen Ames; former CIA officer convicted of espionage.

Interestingly, Ames did not make any attempts to hide his contacts with the Soviets when he started spying for the KGB. Recruiting Soviets to spy for the CIA was his job responsibility and this provided Ames the best cover he could ever hope for.

Having such a strong justification for recurring meetings with the Soviets, Ames actively engaged in espionage against the U.S. Every meeting with his Soviet asset turned handler paid Ames thousands of dollars. Ames reportedly received sums ranging from $20,000 to $50,000 every time he had lunch with his Soviet contact.

For Ames, his Soviet side hustle proved very lucrative. During nine years of spying, Ames received $2.5 million in cash stateside and had another $2.1 million earmarked for him in Moscow. His total earnings from espionage activities totaled approximately $4.6 million, making him the highest paid spy in American history.

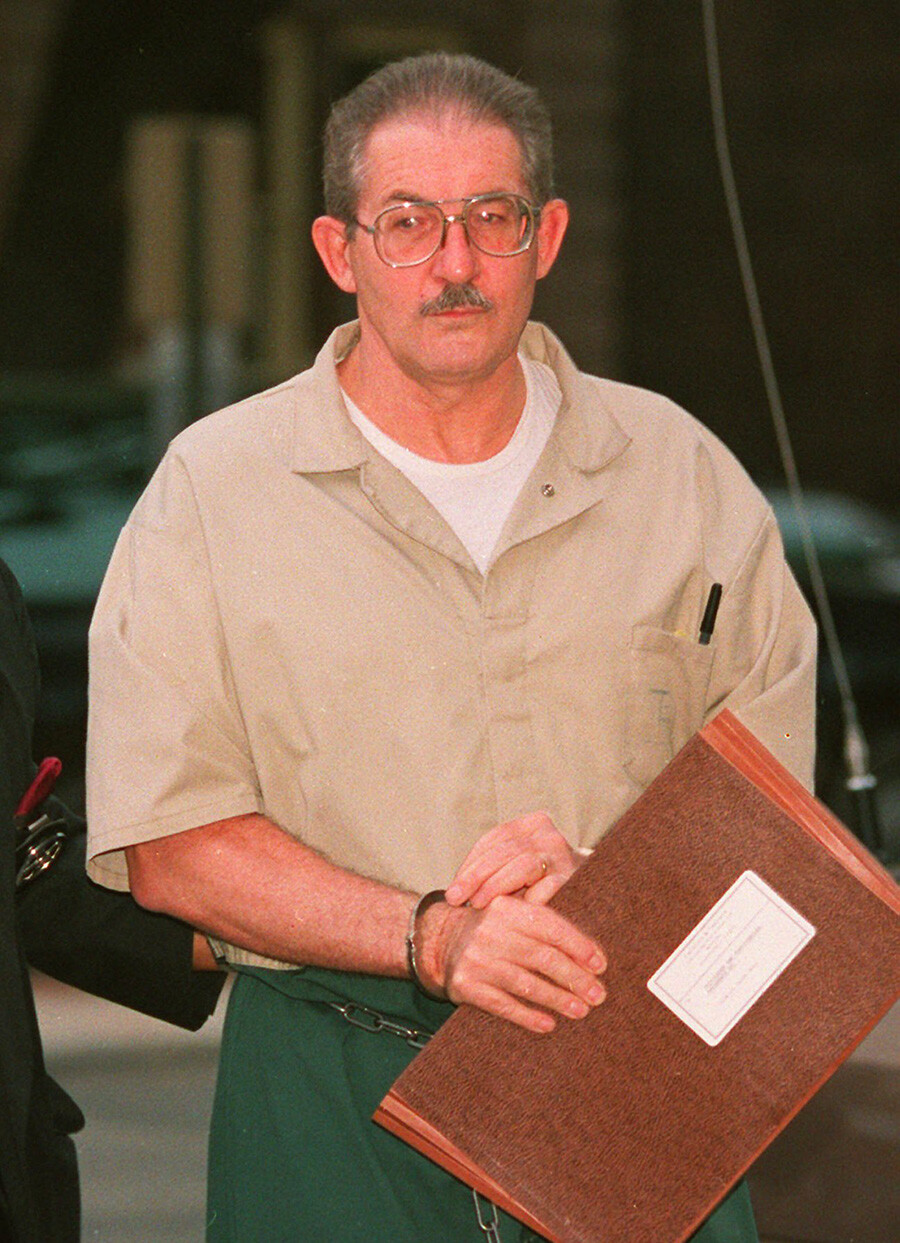

Former senior Central Intelligence Agency officer Aldrich Hazen Ames is led from U.S. Federal Courthouse in Alexandria, 22 February 1994.

Former senior Central Intelligence Agency officer Aldrich Hazen Ames is led from U.S. Federal Courthouse in Alexandria, 22 February 1994.

The Ames family did not shy away from spending their earnings in an extravagant manner. Ames paid $540,000 for a new house in cash, bought a luxury Jaguar car, had expensive cosmetic dentistry and amassed tailor-made suits. His paramour María del Rosario Casas Dupuy regularly went on shopping sprees and produced enormous telephone bills by regularly calling her family in Colombia.

Eventually, Ames’ lifestyle raised suspicions within the CIA. He explained his wealth by arguing that his wife’s Colombian family was rich, but the CIA soon discovered that it was false.

Aldrich Ames in 1994.

Aldrich Ames in 1994.

Dan Payne, a financial expert on the CIA mole hunt team, pulled Ames’ financial records for analysis. The counter espionage team compared installments into Ames account with the chronology of his whereabouts and activities throughout the years and discovered an alarming pattern: Ames’ meetings with the Soviet diplomat he was claiming to be recruiting correlated with large deposits into his account.

“When [Sandy Grimes, a member of the CIA mole hunt team] realized this, she ran to the front office to tell Paul Redmond that Rick Ames was the spy,” said Jeanne Vertefeuille.

The arrest

Probing Ames further, the mole hunt team gathered incriminating evidence. When they learnt Ames was scheduled to move to Moscow for an assignment as part of his CIA job, they decided it was now or never.

On February 21, 1994, Ames was arrested by the FBI when he left his house after a false call by his boss who asked him to come to the CIA to discuss details of his upcoming trip to Moscow.

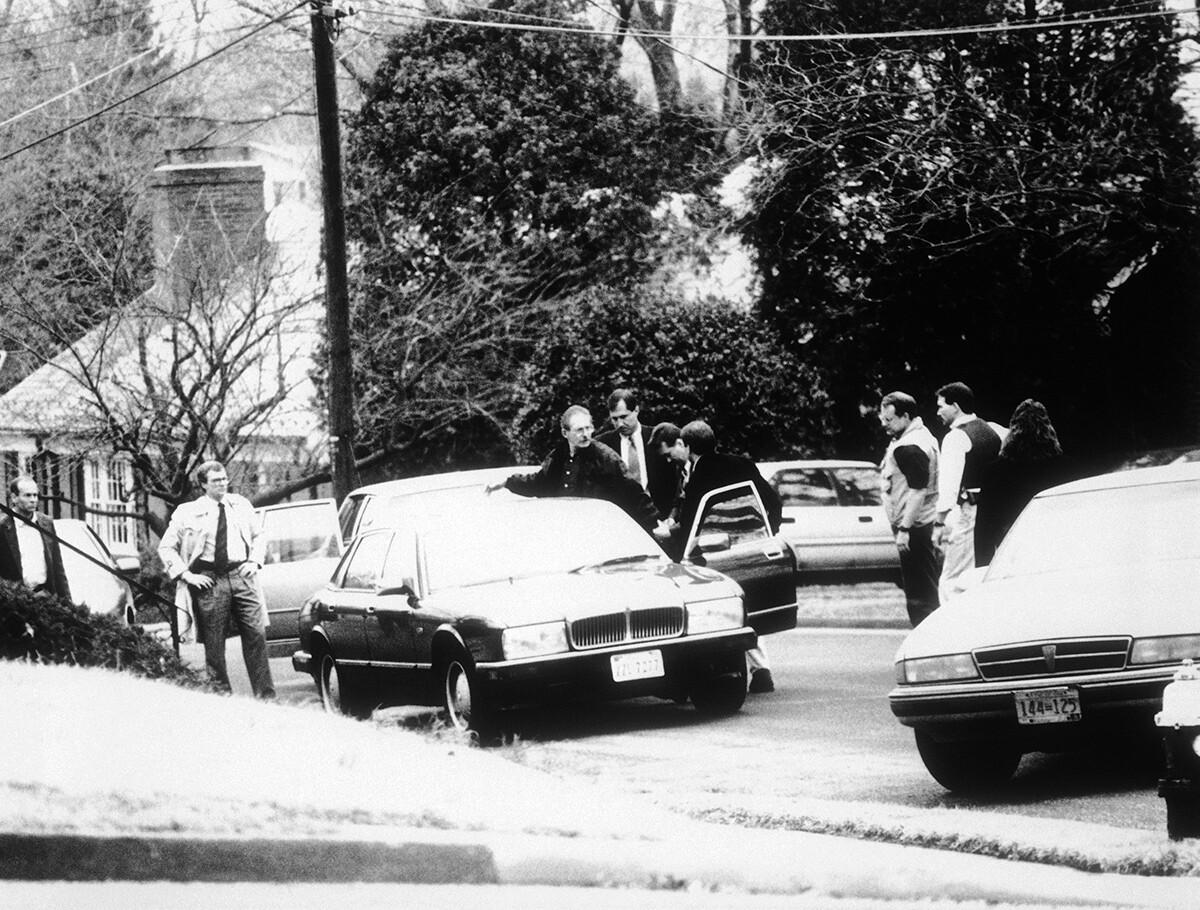

FBI, agents arrest CIA officer Aldrich Ames, center, over car, in Arlington, Va., Feb. 21, 1994.

FBI, agents arrest CIA officer Aldrich Ames, center, over car, in Arlington, Va., Feb. 21, 1994.

“We felt great relief when we heard he had been caught. We were always worried that he was going to get away with it,” said Vertefeuille.

The next day, Ames and his wife were charged with spying, tax evasion and conspiracy to commit espionage against the U.S. Ames pleaded guilty and received life imprisonment. As part of the plea bargain, Ames’ wife received a five-year prison sentence.

As of February 2023, 81-year-old Aldrich Ames continues to serve his life sentence in the medium-security Federal Correctional Institution in Terre Haute, Indiana.