How did the KGB work?

From its inception and until the end of the Soviet Union, the KGB was a prominent force in Soviet politics and society. Its masterful covert intelligence operations and sabotages on foreign soil cemented the Soviet Union’s superpower status, but its ruthless crusade against Soviet dissidents severely tarnished its reputation within the USSR.

The ‘sword and shield’

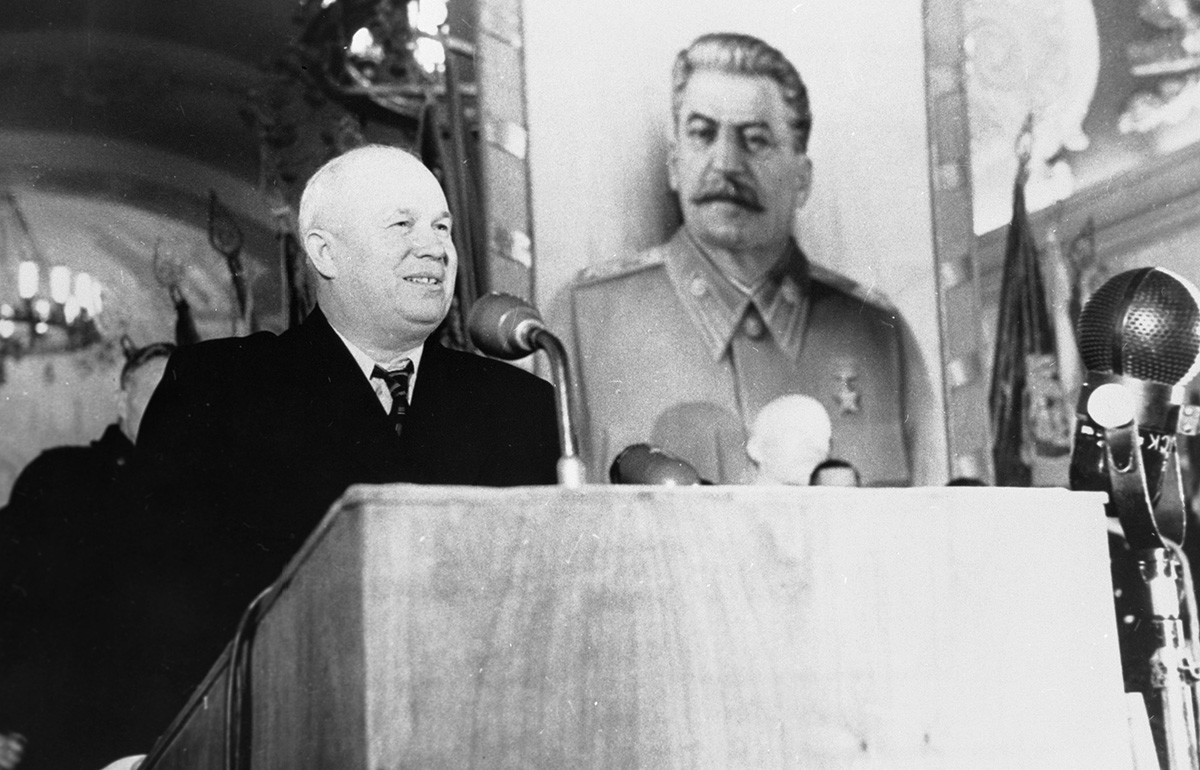

The history of the KGB began in 1954, when Premier of the Soviet Union Nikita Khrushchev sought to replace the NKVD — the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs, which operated under Joseph Stalin, enabling the dictator to consolidate power and carry out purges in the USSR in the late 1930s — with a new institution.

Nikita Khrushchev in 1952, a year before Stalin's death.

SputnikThe newly formed KGB — the abbreviation stands for Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti (Committee on State Security) — was designed to be accountable to the Soviet political leadership, despite being formally subordinated to the Council of Ministers, de jure government of the USSR, which was de facto less powerful than the Central Committee of the Communist Party (CPSU).

The proclaimed official purpose of the KGB was “to protect the Socialist state from the encroachment of external and internal enemies, and to protect the state border of the USSR”.

In practice, the newly established security apparatus became the “sword and shield” of the CPSU, the country’s de facto political leadership. Its raison d’être was the protection of the CPSU, ensuring the stability of the USSR’s political system, suppressing opposition and dissidents, gathering intelligence, overseeing counter-intelligence activities in the USSR, conducting clandestine operations abroad and protecting Soviet borders, to name just a few.

Directorates and branches

Structurally, the KGB was organized into ten main directorates, five special branches and a few administrative departments designed to facilitate the former’s work.

Each of the main directorates had its own narrow specialization. Various directorates administered seemingly unrelated security matters that, put together, formed a comprehensive approach to security within and outside of the USSR.

For example, the seventh main directorate was tasked with surveillance. Agents of the directorate followed foreign diplomats, common visitors and high-profile foreign officials wherever they went in the Soviet Union. In a nutshell, the seventh directorate was the eyes and ears of the KGB inside the USSR.

A monument to Dzerzhinsky in front of the KGB building in Moscow, the USSR.

Vladimir Vyatkin/SputnikThe KGB was known for its highly creative methods for eavesdropping on the U.S. embassy personnel in Moscow. Once, Soviet agents modified typewriters used by the embassy staff.

“Inside that typewriter was a structural piece of aluminum that went from one side of the typewriter to the other. What the Soviets had done through a shipping channel [...] is, basically, took the typewriters apart and replaced that bar with a bar that looked exactly the same, but had been machined out. And discrete electronics had been put inside that aluminum bar, which appeared on the surface to be solid, but it actually was hollowed out. What the electronics would do, every single key that was typed on the typewriter would be stored in a pretty small buffer inside that bar and when the buffer was full, the contents of that buffer would be transmitted through an RF signal to a nearby Soviet listening post,” said Jim Gosler, a former Director of the Clandestine information technology office at the CIA (retired), commenting for a Netflix documentary.

For the U.S. diplomats, the bugged typewriters were only the tip of the iceberg. The whole building was full of hidden wiretapping devices.

The U.S. Embassy in Moscow (above). Below is one of more than 40 secret microphones found in the American Embassy in Moscow.

Bettmann/Getty Images; APWhen the Russians built a new U.S. embassy in Moscow in the late 1970s, the KGB stuffed it with bugs at the bricklaying stage.

“The only way to make that building secure was to chop off the top three floors or so of the building and throw it away and rebuild them using U.S. labor and U.S. material that was [brought] in from the U.S.,” said Ray Parrack, former Senior technical intelligence officer (retired) at the CIA, also commenting for the above-mentioned documentary.

Other directorates oversaw counterintelligence (second main directorate), encryption and decryption work (eighth main directorate), security of the party leaders (ninth main directorate) and political stability of the Soviet state (fourth main directorate).

Yet at the forefront of the USSR’s Cold War struggle with the West was the first main directorate famous for its notorious spy-rings and clandestine high-risk operations abroad.

At the frontline

The former CIA director Allen Dulles once described the KGB as being “more than a secret police organization, more than an intelligence and counterintelligence organization. It is an instrument for subversion, manipulation and violence, for secret intervention in the affairs of other countries.”

Indeed, KGB agents made a few splashes abroad and influenced the course of the Cold War in many ways. KGB agent Bohdan Stashynsky is known to kill two anti-Soviet Ukraine nationalists hiding in West Germany with an elaborate poison mist gun which left no signs of forced death on the victims.

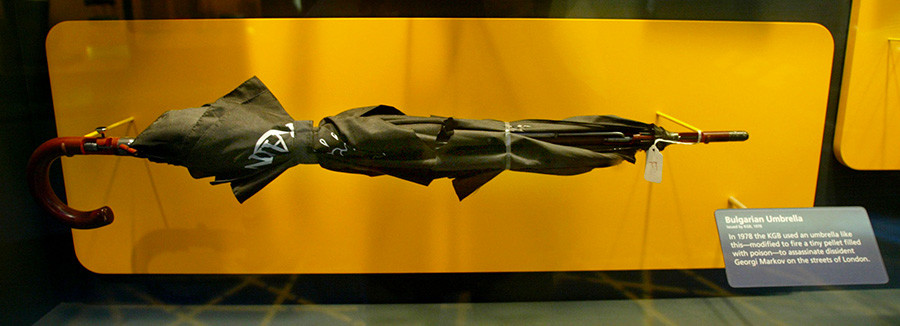

It has been speculated that the KGB might have helped Bulgarian secret police to murder dissident writer Georgi Markov who defected from the USSR’s ally in 1978 with a poisonous weapon disguised as an umbrella.

A replica of the umbrella used to kill Bulgarian dissident and radio broadcaster Georgi Markov is displayed at the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC.

Mark Wilson/Getty ImagesThe KGB has also been involved in large-scale operations abroad, including a covert operation to mount an assault on the well-protected Tajbeg Palace in Kabul and kill Afghan leader Hafizullah Amin, in order to induce a regime change in the country in 1979. Earlier, the agency played a key role in suppressing the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 by arresting some of its leaders.

At the peak of the Cold War, the KGB ran spy-rings and networks of informants in corners of the world. The agency actively worked on U.S. soil and recruited U.S. military officers and intelligence agents like U.S. naval officer John Anthony Walker Jr. and CIA officer Aldrich Ames to siphon U.S. military secrets to the USSR. Although it is impossible to establish an exact number, some researchers believe the number of informers working for the KGB during the Cold War range in millions.

Identification documents used by spy John Anthony Walker, including a driver’s license, U.S. passport, and military ID.

FBIThe era of the KGB ended with the Soviet Union collapse and the end of the Cold War in 1991. The notorious security agency, that has guarded the Communist Party’s interests inside the USSR and abroad for 37 years, has been dissolved and replaced with the modern Federal Security Service, aka the FSB, which inherited many of the KGB’s functions in modern Russia.

The statue of the founder of the KGB, Felix Dzerzhinsky, is toppled off its pedestal in front of KGB headquarters in Moscow, Russia, in August 1991.

Alexander Zemlianichenko/APClick here to find out who could work for the Soviet KGB.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox