"Peter the Great uncovers the conspirators in Tsykler's house on February 23, 1697" by Adolf Charlemagne (1826-1901), 1884

Russian MuseumMalicious intent against the life and health of the tsar and members of his family, likewise any preparations for an attempt on his or their lives, was the most serious crime in Russia. If the plot was proved, all its participants, as well as those who knew of the plot and did not inform on it, were subject to the death penalty.

In the 17th century, in order to denounce an attempt on the sovereign’s life, it was necessary to say the words: “The sovereign’s word and deed!” – which meant that the one who spoke them knew about the word (conspiracy) or deed (attempt) on the tsar. Such people were to be immediately sent to Moscow to the state security organs.

According to the Nomocanon, a Greek collection of Ecclesiastical law, applied in Russia in both civil and church law, a malice against the tsar was the first reason for an immediate divorce for both men and women. Of course, a man who plotted something against the tsar, and told others about it, was deserted by society and denounced in nine out of 10 cases.

"Grief," by Ivan Tvorozhnikov, year unknown.

Novgorod State United Museum-ReserveRussian church teachings prescribed that one should take care first of all of one’s family and servants living at home. The ‘Ismaragd’, one of the teaching books, expressly stated: “It is hypocrisy to bestow [good] on orphans or strangers, while one’s clan and servants are naked, barefoot and hungry.”

Respect for one’s parents and children was the first duty of every Christian. Parents were honored and obeyed. Although, formally, the eldest man was considered the head of the family – but if he had an elderly mother, her opinion was still final. Disrespect for the elderly mother and father, as well as leaving one’s own children without food, sons without an inheritance and daughters without a dowry, led to universal condemnation.

According to the main legislative text of the 17th century, the Sobornoye Ulozhenie of 1649, such a person was to be whipped – a severe corporal punishment that often led to disability and death.

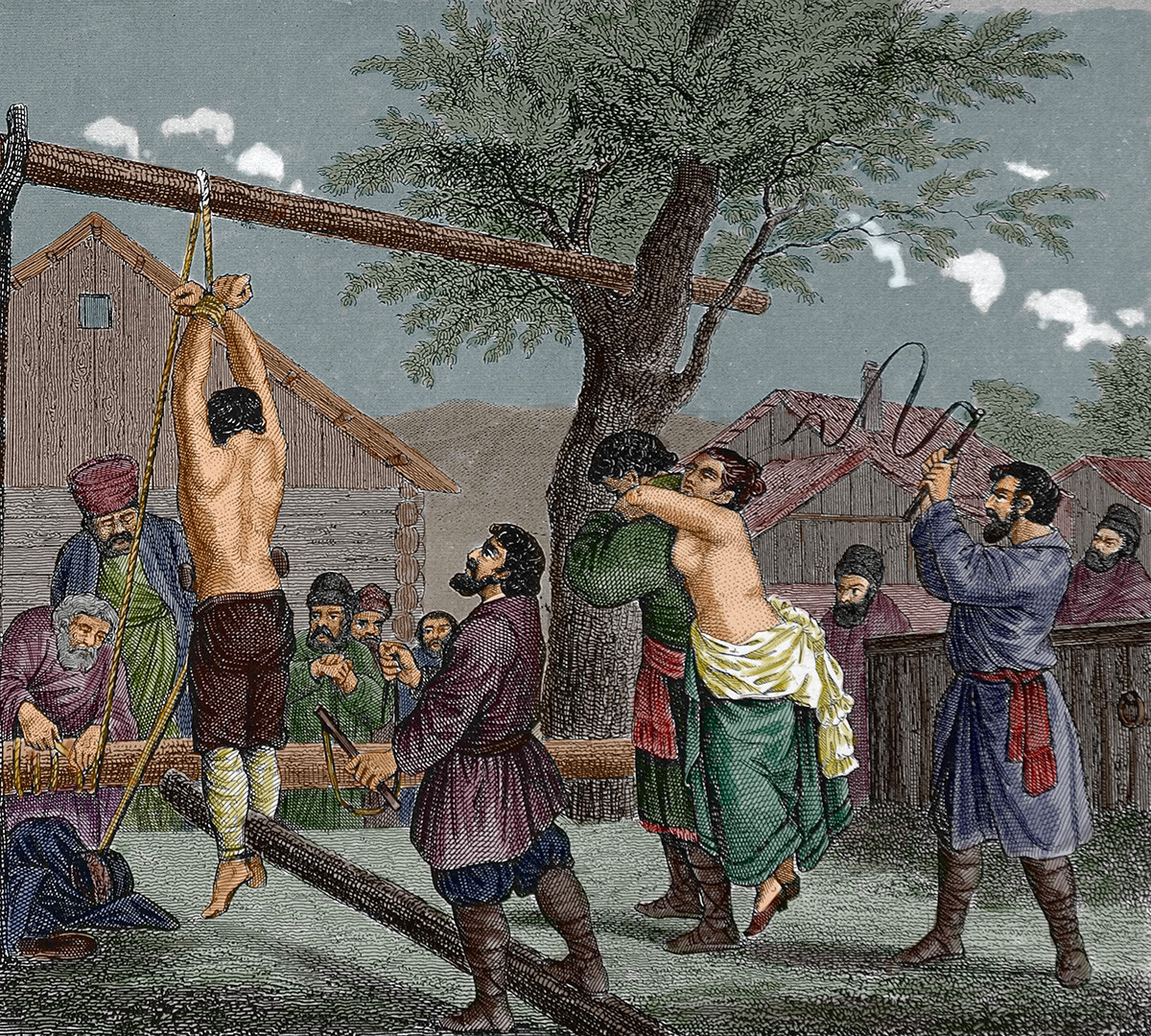

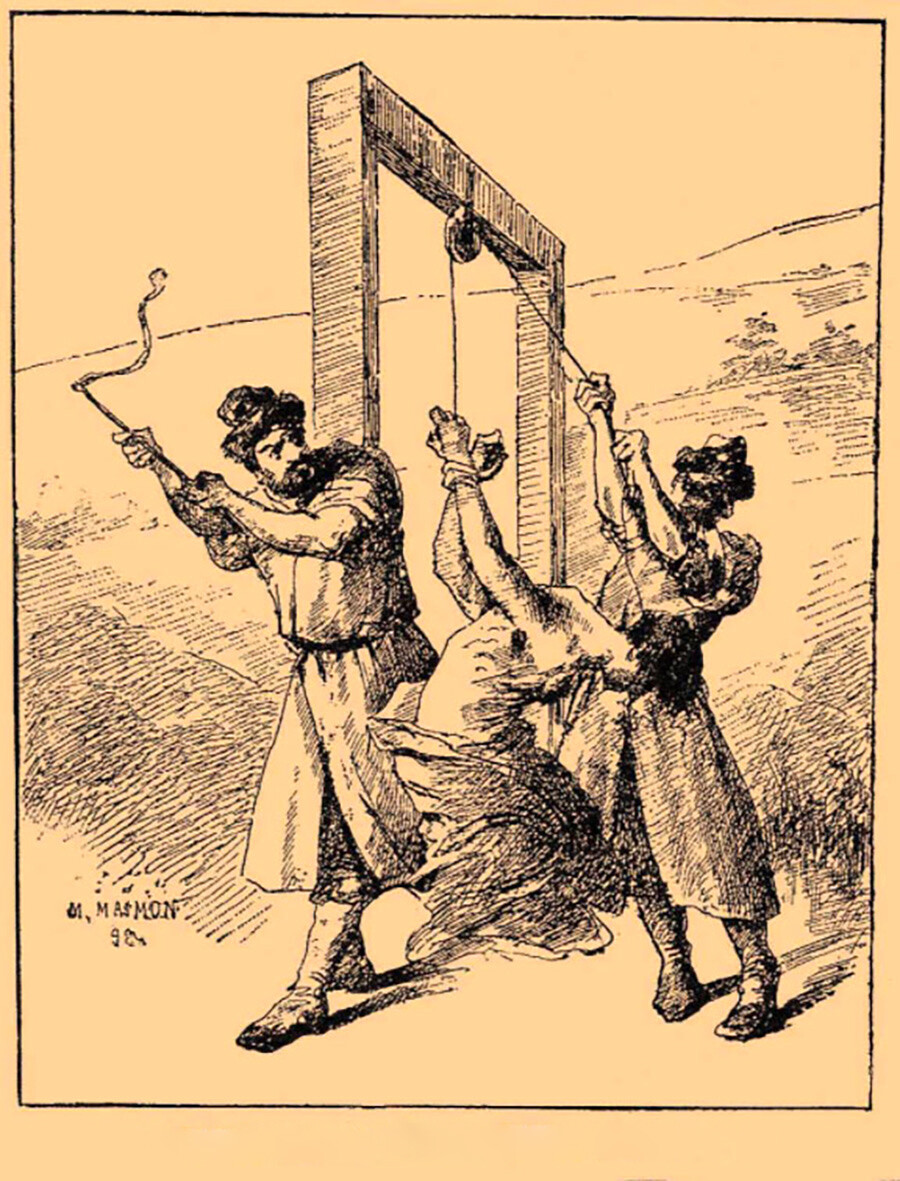

Punishment with a whip

Legion MediaMurder of family members and, in particular, patricide and the murder of one’s own husband by his wife were considered the most terrible crimes in Russia. If, in Ancient Rus’, it was still possible to pay a fine for patricide, albeit a huge one, then, from the middle of the seventeenth century, murderers of family members were punished with death.

The murder of one’s own husband by his wife was punished with expressive cruelty – by burying her alive. Such wives were put standing in a pit – usually in a public place – and buried in the ground up to their throats or chests. Guards were assigned to the executed woman so that relatives and friends could not give her food or water. Only priests were allowed to approach her to read prayers. Anyone passing by was allowed to throw money for the unfortunate person’s funeral.

"The local court," by Mikhail Zoshchenko, 1888

Tretyakov GalleryIf the execution was hastened, the earth around the buried person was rammed – the person suffocated, panicked and died. Usually, however, the buried were left to die slowly. The execution could last for days – but one could also be saved. In 1677, Fetyushka Zhukova from Vladimir, unable to endure her husband’s beatings and torments, beheaded him with a scythe. Buried alive, she remained in the pit for a full day; but she was then sent to a monastery at the request of a kindhearted nun. Fetyushka’s candid confession and the awareness of those around her that her husband had been killed “for the cause” – he was known as a wife beater – played a role, of course.

The murder of a parent’s own children was considered a grave crime, but there were many cases of babies being killed by inexperienced young mothers by unconsciously laying over them during sleep and suffocating the toddlers. Such murder was always considered unintentional and was punished by years of fasting, as was expulsion of a fetus with potions, for which one could be excommunicated for life. A more severe punishment was imposed for the murder of children born out of wedlock – since 1649, it was punishable by death.

Punishment with a whip

Public domainIn the pre-Christian period of Russian history, blasphemy was considered to be the desecration of sacred pagan objects. Violation of pagan rites and rituals, insulting pagan gods, defacement of pagan holy places were all considered a gross religious misconduct.

According to the ‘Tale of Bygone Years’, in the year 983 in Kiev, five years before the Baptism of Russia, Vladimir I was going to sacrifice John, the son of a Varangian named Feodor. Both of them were Christians and the father refused to give up his son, publicly condemning paganism. As Karamzin wrote: “The Kievans tolerated Christianity, but the solemn blasphemy of their faith produced a revolt in the city.” Fyodor and John were subsequently killed.

Early Russian laws contained no penalties for blasphemy. The Nikonovskaya Chronicle reports that in the year 1004, monk Andrian, a scopetz (belonging to a sect which practiced castration) who “reproached church laws and bishops”, was placed in prison by Metropolitan Leont, where “little by little he was reformed and came to repentance”.

But, in 1371 in Novgorod, the pagans were already being dealt with by the people themselves. Three heretics who spat on crosses, threw icons into cesspools and taught this to the “weak of heart”, were drowned by the Novgorodians in the Volkhov River.

In 1505, any “dashing heretic” would be punished by death or life imprisonment. Subsequent laws confirmed and increased the penalties for blasphemy. In 1649, the law said the blasphemers, “having been convicted, shall be burned”. Such cases were decided not by the Church, but by a secular court. The punishment by burning, introduced by the state, launched a nightmarish wheel of self-immolations of the Old Believers in Russia.

"Father in law," by Vladimir Makovsky, 1888

Russian MuseumRussian lust was perceived by foreign travelers as something absolutely savage. The Danish nobleman Jakob Ulfeldt, who visited Moscow during Ivan the Terrible’s reign, was shocked to see a woman showing him her “shameful parts” from the window of the house next to his. Foreigners were especially shocked by the Russian custom of jumping out of the bathhouse naked. Adam Olearius, a 17th-century German traveler, wrote that, on the Red Square, he saw women for sale: “Standing, holding rings in their mouths (most often – with turquoise) and offering them for sale. As I heard, at the same time as this trade they offer customers something else.”

The Russian church, however, fought sternly against any manifestations of carnal lust. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, “sin of Sodom” meant everything that was forbidden by the church: same-sex relationships, bestiality, incest. However, all kinds of heterosexual sexual intercourse, except for the “missionary” position, were also forbidden and considered a “great sin”. The “woman on top” position was punished by fasting for five years.

Today, the penitential books of the Russian Orthodox churches, the books containing questions asked of men and women in confession, are read like pornographic literature. “Did you climb on your female friend or did your female friend climb on you, creating, as with your husband, sin? Or did you put your tongue in anyone’s mouth? Or winked at another man because of lust? Or did you show your shame to anyone?” – these are the questions priests asked women during confessions in the 16th and 17th centuries in Russia.

The penalties for fornication and sodomy varied according to the seriousness of the offense and the gender of the convict. Same-sex relations between women, if found and proven, were punished by burning, but, in reality, were just punished with fasting and whipping. It would have been too severe a punishment to be executed, since there are numerous sources that mention lesbian relationships. The same-sex relations of men were, on the other hand, unambiguously punished by burning alive.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox