Why there was always a shortage of EXECUTIONERS in Russia

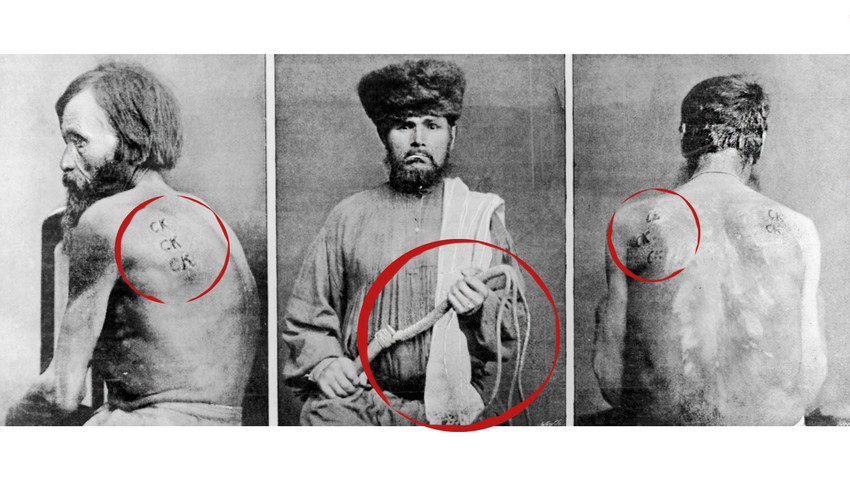

From left to right, a Siberian convict branded with the letters' CK' for attempting to escape, the executioner of Kara and a prisoner scarred by the 'knout' or whip, circa 1860.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesMost of the gruesome executions during the reign of Ivan the Terrible (1530-1584) had to be carried out in his presence and by his closest guards. In 1570, former head of Moscow’s foreign affairs Ivan Viskovatov was executed for treason: the tsar’s closest oprichniki took turns cutting off Viskovatov’s limbs and disfiguring his body.

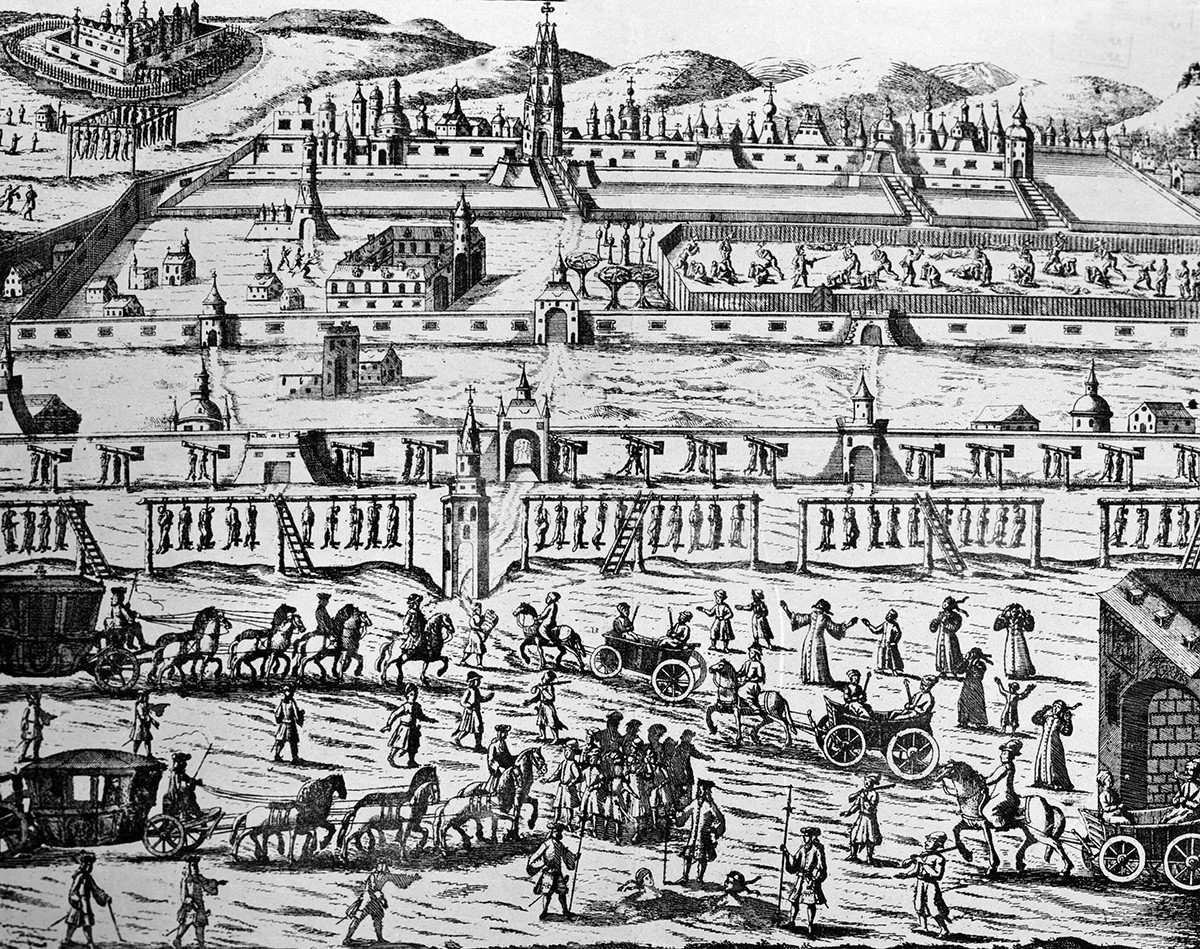

"The execution of the streltsy in 1698" from the book by Johann Korb. From the funds of the State Historical Museum.

Mikhail Uspenskiy/SputnikIn 1698, Peter I personally executed five streltsy guards during a mass execution after a riot in Moscow. His ministers, princes Romodanovsky, Golitsyn, and Menshikov then also tried their hand at execution. But why did the tsar and his companions have to do it themselves? Surely, not everyone among Russia’s elite was a born sadist?

Executions as a trade

In Russia, there weren’t any professional executioners for a long time. Before Moscow became a state, executions were carried out by militias under the command of Russian princes, and this continued in the 16th century. But later, in 1649, the Council Code (Sobornoye Ulozhenie), the Moscow Tsardom’s code of laws, was introduced, bringing about a need for professional executioners to carry out not so much death penalties, but corporal punishment.

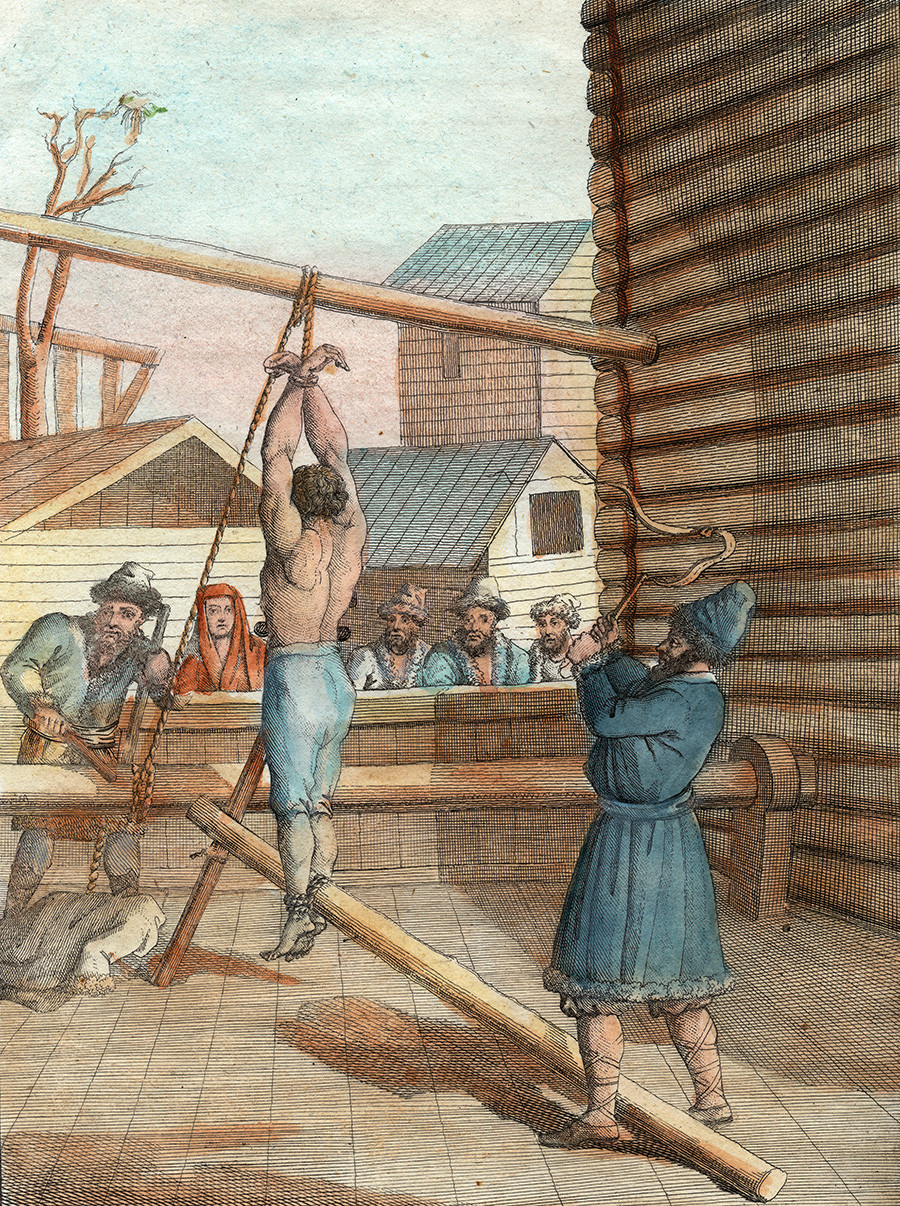

Coloured engraving depicting punishment with a Great Knout, a scourge-like multiple whip, in Russia, circa 1800.

Getty ImagesOn May 16th, 1681, the Boyar Duma ordered every town’s voevoda (head of local administration) to hire executioners from local people. If no one applied, the executioner was to be chosen deliberately from “free-rolling people,” “so no town is without an executioner.” The annual pay was 4 rubles – not very much, and less than an army soldier’s, which was 6 rubles. (In those times, a dinner would cost 0.04 – 0.05 rubles).

Obviously, the law implied that executioners had another way of making money – the relatives of those condemned to scourging or whipping were ready to pay to make the execution go easier, or be skipped altogether. This is described in detail by Friedrich Zeider, a priest who was condemned to whipping and exile during the reign of Paul I for ordering forbidden books from abroad.

“I was led to the pillory, to which they tied my hands and feet. When the executioner threw a belt around my neck to tie my head and arch my back, he tightened it so tightly that I cried out in pain. Having finished all the preparations and bared my back for receiving fatal blows, the executioner approached me. I expected death with the first blow… Suddenly something whistled in the air. It was the sound of a whip, the most terrible of all whips. Without touching my body, the blows only slightly touched the waistband of my trousers…”

The executioner was bribed by some well-wishers, and so Friedrich Zeider was ‘executed’ only visibly. Such bribes made up the executioners’ main income – many convicts had relatives who wanted them to live, (lashings could result in death). Still, there weren’t many candidates for the executioner’s position: Russian society largely shunned the gruesome craft.

A godforsaken profession

Whipping (from Achille Beltrame, La Domenica del Corriere. The horrors of Russian prisons.

Getty ImagesThe Orthodox Church detested executioners. According to Orthodox worldview, an executioner chose greed over mercy. So, members of the profession were not allowed to take communion or other Orthodox sacraments. Executioners were also shunned by the wider public – they lived apart from the community, and so much as eating at the same table and being friends with them was considered unbecoming.

By the 1740s, there was a considerable shortage of executioners, so the Senate raised the executioner’s wage to 9.5 rubles. During Paul I’s reign, the wage was raised to 20 rubles, but this didn’t help – very few people volunteered for the position. In 1805, the government allowed to hire executioners from convict ranks – but only those who were condemned for minor offenses – defectors, thieves, swindlers etc.

Most of the convicts who were exiled to Siberia had to be whipped and branded before departing Central Russia – and without executioners, this couldn’t be done, so by the 1810s, almost all executioners were ‘drafted’ this way. This actually saved money – free-hired executioners demanded their pay, while executioners hired convicts were only paid from time to time – their position afforded them virtually no rights whatsoever.

Trained to maim

The way branding was performed on a convict's face / The tool used for human branding, early 19th century.

Demidov Family Museum; Archive photoBeing made up of mostly convicts doing time, executioners lived in prisons... They were, however, allowed more freedom – many of them were shoemakers or tailors. But they also had to improve their skills, so they would also make mannequins out of birch bark, and exercise their lashing skills. Training in this pursuit required about a year of daily classes. Therefore, newcomer executioners spent a long time as apprentices – they learned to witness the execution, to pay little attention to blood and screams, among other things.

By the start of the 19th century, there were so few executioners in Russia that they went on ‘work trips’ to different regions – prisons in some parts of the country didn’t have any executioners. By the time one arrived, several dozen people were usually accumulated in prisons, awaiting execution. The executioner would stay for one or two days to complete his tasks, and leave for another town. But when there was a need to punish hundreds or even thousands of people, these business trips lasted for months.

Painter Lavrentiy Seryakov remembered how an execution was usually performed in the 19th century. “A pommel horse was dug into the parade ground. Two executioners were walking nearby, guys of about 25 years old, well-built, muscular, broad-shouldered, in red shirts, pleated trousers and slouchy boots. Cossacks and a reserve battalion were stationed around the parade grounds, and behind them, the relatives of the convicts were crowding.

The hanging of the Decemberists. A still from "The Captivating Star of Happiness" movie, 1975.

Vladimir Motyl/Lenfilm, 1975“At about 9 AM, the condemned arrived at the place of execution – 25 people. They were placed on the pommel horse in turn. The first was assigned 101 lashes. The executioner moved 15 steps away from the pommel horse, then slowly began to walk towards the condemned, his whip dragging in the snow. When the executioner came closer, he waved the whip high with his right hand, a whistle was heard in the air and then a blow. It seemed to me that the executioner cut through the skin very deeply from the first time, because after each blow, he wiped a handful of blood from the whip with his left hand. At the first blows, a dull groan was usually heard among the executed, which soon ceased, then they were chopped up like meat. After laying 20 or 30 strokes, the executioner would approach a bottle that was standing right there in the snow, pour a glass of vodka, drink it and get back to work. All this was done very, very slowly.”

On April 17th, 1863, Emperor Alexander II famously banned corporal punishment (maiming, lashing, human branding etc.) in Russia. So the few convicts/executioners who were active were just put back in prisons as ordinary convicts for the rest of their sentences. In April 1879, after military district courts were granted the right to impose death penalty in the army, there was only a single executioner for the whole of Russia – a man by the name of Frolov. He traveled from city to city under military escort to hang the condemned.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox