Philip Malyavin, "Peasant Girl", 1920

I. I. Mashkov Museum/Public DomainIn 1647, a Russian woman by the name of Avdotya denounced her husband Nikolay: "He chained me by the legs, and tied me to a ceiling beam, and tortured and beat me, and hung me for a day". Cases of wife-beating were common in Russia. There even were guidelines on how to punish an unsubmissive wife in the Domostroy, a renowned 16th century collection of household rules and instructions for the nobility on how to live a proper family and religious life (by the standards of that era): "Punish her in private, but, having punished her, treat her with words, and love her".

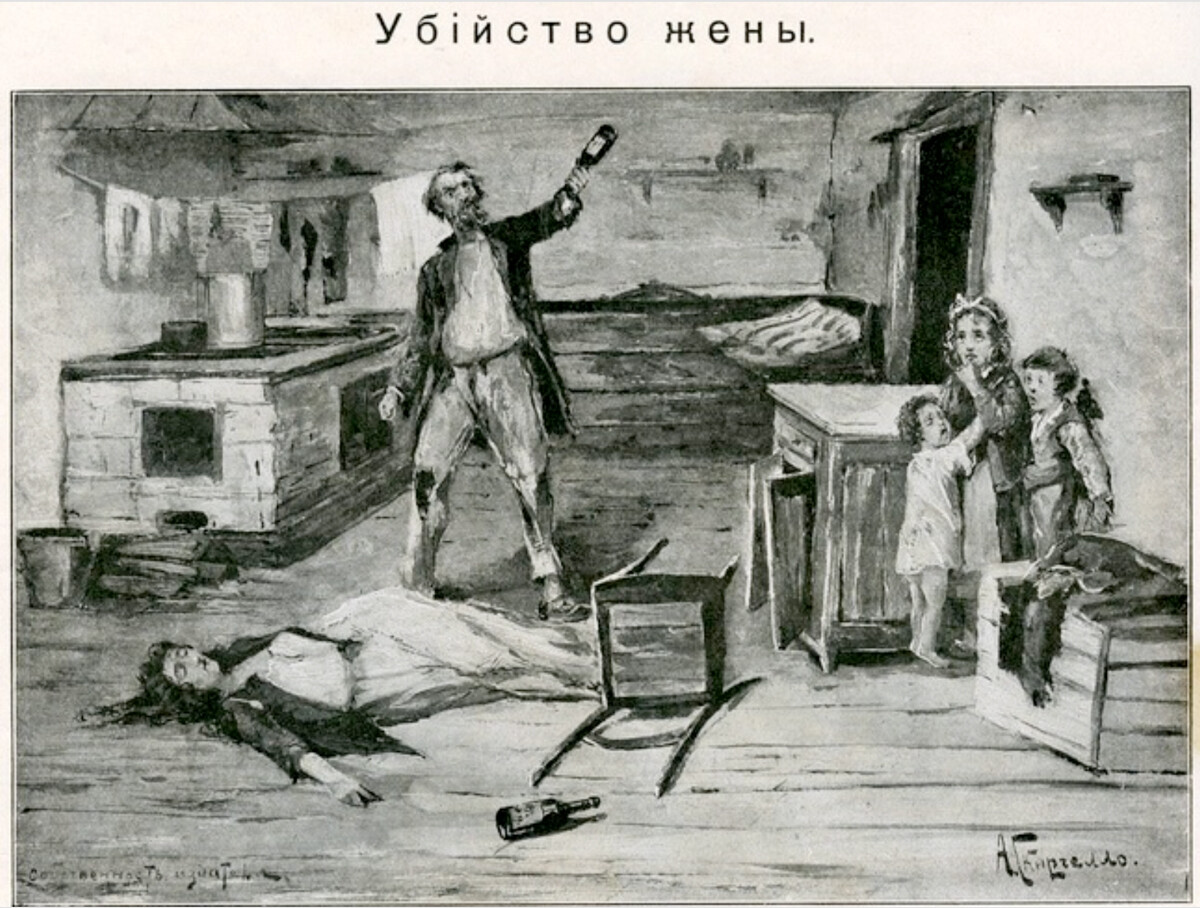

"Murder of a wife," from an illustrated book "Drinking and its consequences," Moscow, 1913.

Public DomainUnfortunately, domestic violence was the norm in Russia. And the situation was similar in Europe at that time, according to historian Nada Boszkowska, who said that books of that period recommended husbands to "punish" and "teach" their wives in order to maintain patriarchal control and order at home.

In most cases, incidents of domestic violence occurred while the husband was drunk. In south Russia, an ataman from Usman put his naked wife in nettles, harnessed her to a plow, etc. English physician Samuel Collins, who was the personal doctor to Tsar Alexis I from 1659-1666, mentioned a case when a priest beat his wife with a whip, then put her in a dress soaked in vodka, and set her on fire. Another priest chained his wife and burned her body with a red-hot poker. These are just a few horror stories about how some husbands in the 17th century abused their wives.

Incidents of murders and the suicides of wives following repeated domestic violence are often mentioned in historical sources. However, the husband perpetrator was rarely punished, even if he murdered his wife, unless she had powerful relatives or if someone from the Church interceded.

READ MORE: What would you be CANCELED for in Old Russia?

Even in such cases, the court and Church often decided to send a battered wife back to her husband. According to the Russian Orthodox Church and Russian civil law, the husband was allowed to "teach" his wife, but he was not to do it "out of spite," not to torture her and threaten her life. According to Russian concepts, "teaching" was "basic" beatings, while "excessive" beatings and “beating to death" were considered a crime.

Did Russian wives ever try to resist and fight back? Did they have any recourse? Yes, they did.

"I won't let you in!' by Vladimir Makovsky, 1892

National Museum "Kiev Art Gallery"/Public DomainIf a woman believed that her husband was trying to kill her, she could file a complaint in court, and there are many such complaints in the historical documents. Women usually appeared in court themselves or were represented by their male relatives.

First of all, a husband probably wouldn’t beat a woman whose father or brothers were alive, especially if they were rich and powerful. A man could easily seek justice against another man in pre-Petrine Russia. But, that wasn’t the case for most women. What were the options for women who didn’t have any powerful relatives?

Escape. Most often a woman fled back to her family, then she consulted with her relatives and wrote a complaint against her husband. In such a case, the victims indicated that a husband had threatened his wife's life, which was recognized as an official reason for divorce and trial. However, in 1646, the wife of a Putivl nobleman fled to Lithuania, leaving her own mother and children behind, and she only returned when she found out that her husband had died.

Nuns of the Convent of John the Apostle, in Sura, Arkhangelsk region, early 20th century

Public DomainEscape to a convent. Asking for protection from a bishop, or a religious community – especially at a cloister or convent – was a very good option. Convents often served as places of refuge for women who had fled domestic violence, as well as women who had been forcibly tonsured by their noble husbands when they wanted to marry another. In short, the nuns understood more than anyone else the plight of battered women.

Accusing one’s husband of treason. It was possible to use dastardly means against an abusive husband – a woman could declare "the word and deed of the sovereign" on her husband, saying that he was plotting to murder the tsar or to flee abroad. Such an accusation, even for an innocent man, would most likely have ended in death by torture in a Moscow jail. But it was important to prove this accusation – for example, to prepare forged letters, or to find a witness who would also swear under pain of death that the husband really planned to flee abroad. Otherwise, the death penalty awaited the false witness and all those who signed such fake testimony.

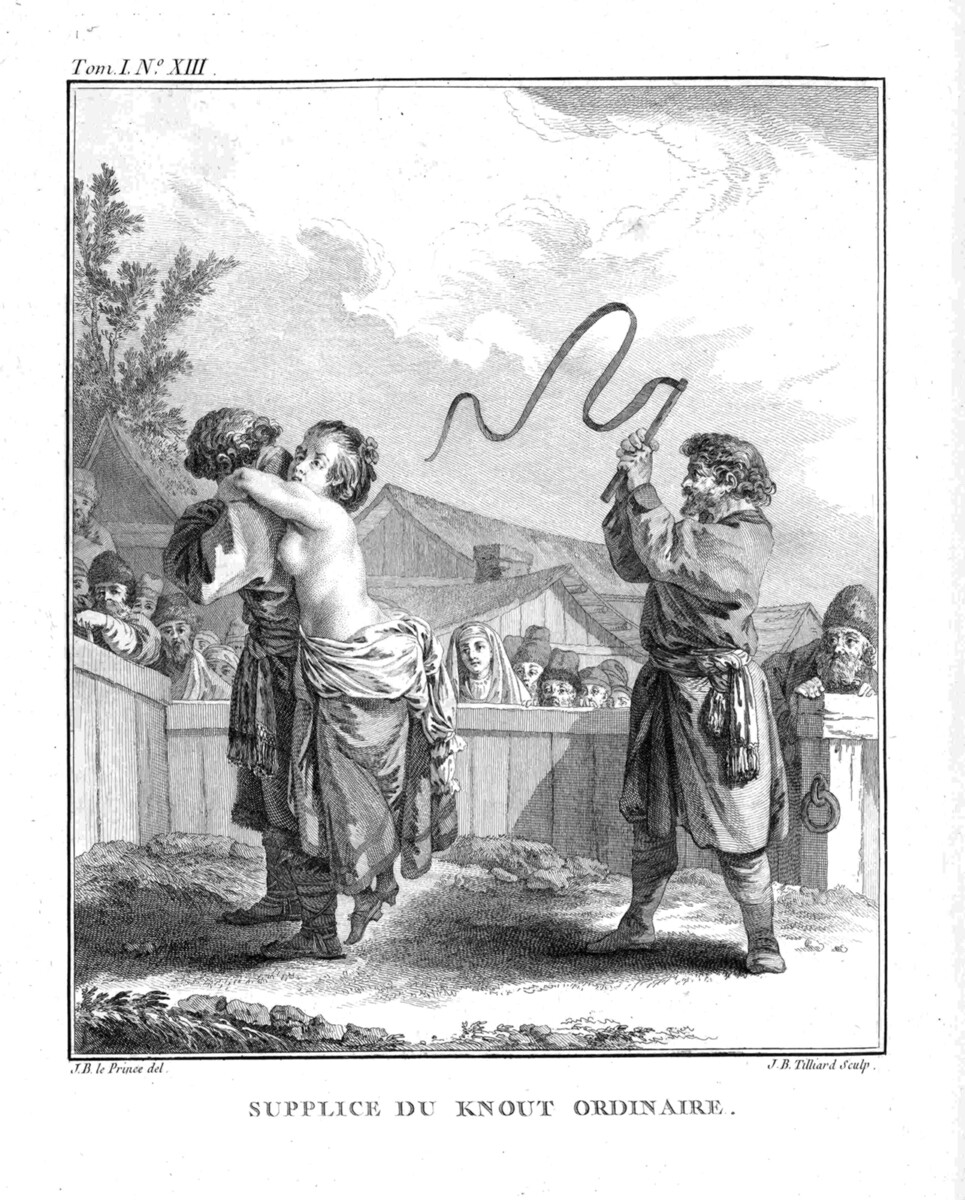

Execution with a whip.

Public DomainA fair trial. By default, the courts often decided cases of domestic violence in favor of the husband. But a fair court decision was possible if a woman had her own money (for example, an inheritance from her father that was considered inviolable and did not belong to her husband), or if she had influential relatives or friends.

Murder. The most desperate women decided to terminate the lives of their tormentors. Cold-blooded murder of an abusive husband, however, was punishable by death through burying alive. So, women who killed their husbands often tried to prove involuntary manslaughter. In 1629, Agraphena Bobrovskaya of Mtsensk stabbed her husband to death with a saber while he was asleep, and testified that she "hit him without deliberate purpose, not loving him" – an obvious contradiction. However, Agraphena insisted that there was no such intent and that in general she had had a panic attack; neighbors testified, however, that she had never had such an illness before. How the case ended is not known to history as there are no documents.

"A sorry sight," from an illustrated book "Drinking and its consequences," Moscow, 1913.

Public DomainIn the town of Kozlov in 1647, recalls Nada Boszkowska, Akulina and her son-in-law Sergey were arrested – they had killed Akulina's husband, the nobleman Artemiy Kuchenev, and threw his body into the river. The murdered man's son denounced his stepmother, who claimed that Artemiy had raped her 8-year-old daughter from her first marriage. Akulina later learned that Artemiy had murdered his first two wives and molested his children, and she decided to kill the villain. How the case ended is also unknown.

"A bender," by Ivan Gorokhov, 1929

Public DomainDo not think that wives didn’t beat or kill their husbands. Domestic violence against men also existed, although such cases were much smaller in number.

The murder of a husband might have been the result of a nefarious plan to gain control of his property since his widow would be his heir. In 1625, the wife of Dmitry Yeremeev from Beloozero tried to stab him to death with a knife while he was in the bathhouse. When that failed she tried to kill him with a spear, but again, he survived the attempt. During her trial, the wife tried to exonerate herself by saying that she was "insane", and so she was punished by whipping.

READ MORE: How did single women survive in Tsarist Russia?

In another case, a soldier from Ustyug claimed that his wife tried to strangle him in his sleep, and later threatened to kill him through witchcraft. And in the city of Kursk, the wife of an iconographer hired three men who subsequently killed her husband in his sleep. We know about this case because the perpetrators were caught.

Women who wished to be widowed, however, often resorted not to murder but rather preferred to accuse their husbands of treason or witchcraft, and were careful to scheme to produce false witnesses and forged documents.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox