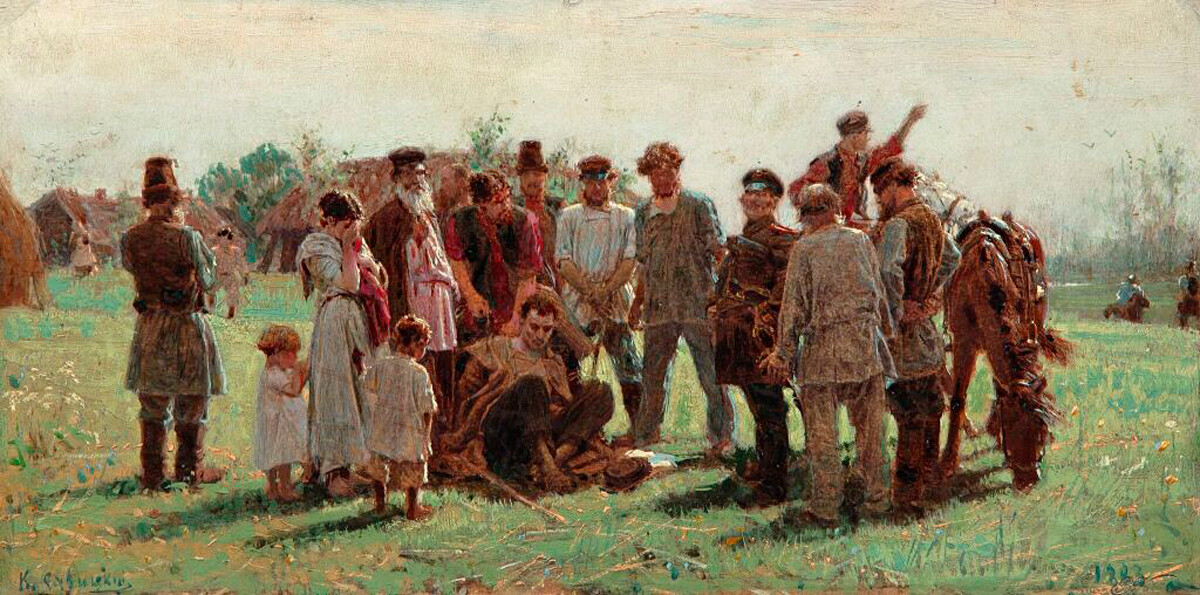

"Suspicious men," 1882, Konstantin Savitskiy

Russian Museum / Public domainAt the turn of the 17th-18th centuries one Russian voevoda (local administrator), traveling on the Volga River near Nizhny Novgorod was "surrounded by three barques of Russian river pirates; each barque had eighteen men. The crew of the voevoda's vessel successfully fought back, and when three of the robbers were killed the others fled.”

This story was recorded by the Dutchman Cornelis de Bruijn. In 1703, he sailed down the Volga to Astrakhan in a boat that carried 52 people with more than forty guns and pistols, and during the night two sentries were constantly on duty. Organized raiders that roamed the countryside in pre-Petrine Russia were truly a huge problem.

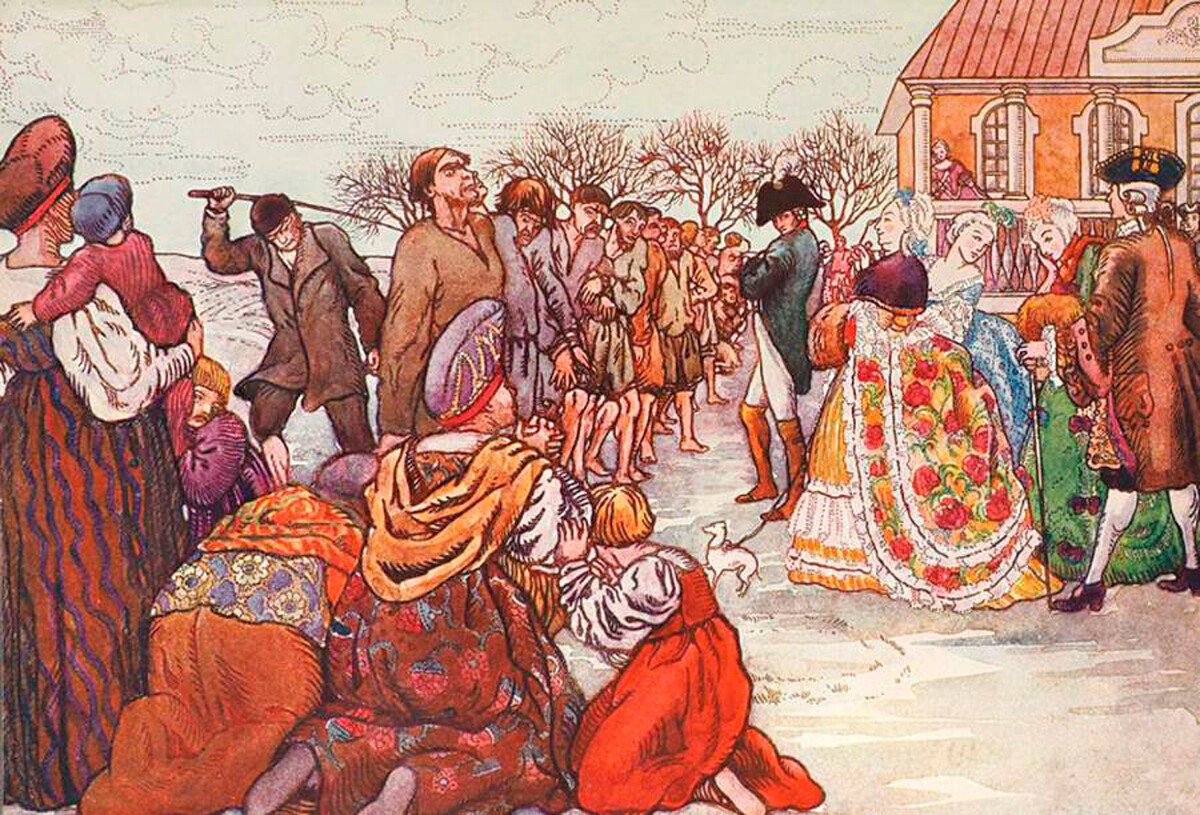

A public execution in the 18th-century Russia, by Nikolay Evreinov

Public DomainThe first Russian code of laws, the Russkaya Pravda, stipulated severe punishment for robbery: all the property of the robber was plundered, and he and his family were killed or sold into slavery. This, of course, did not stop the criminals. Robbers existed in Russia long before the appearance of the regular police and were a serious and common problem.

In 1497, a law was introduced that instructed how to track down criminals, as well as conduct interrogations of the local population in order to find the bandits. Starting in 1539, special institutions for the fight against crime appeared – gubnaya izba (literally ‘the house of penance’) was headed by ‘penance elder’; these were the first ‘local police inspectors’ in Russia. However, it’s clear that these measures did little to curb crime.

Stepan Razin, by Ivan Bilibin, 1935. This is how a glorious highwayman would have looked in Russia. Notwithstanding the fact that bandits were bandits, Russians still glorified them in tales and songs.

Public DomainIn 1724, Russia’s first economist Ivan Pososhkov testified: "In Russia, we have a lot of robbers, sometimes with up to a hundred or two hundred in their gangs.” These raiders often carefully planned their attacks; as a rule, they were highly organized and had a certain hierarchy. However, they could act spontaneously if the opportunity presented itself. They had their own means of transportation and weapons, including heavy guns that often had been stolen from merchants or tsarist officials.

Bandits and marauders had their bases in towns and villages. Setting up and hosting a thieves' den was also a criminal offense. As the polymath and scientist Mikhail Lomonosov wrote in the mid 18th century, "they live by the villages, but they usually come to towns to sell the looted goods.” Lomonosov himself admitted: "Even if officials are sent to track down the robbers, there’s little hope to find out about this evil or even to reduce it significantly.”

READ MORE:5 types of corporal punishment in Russia

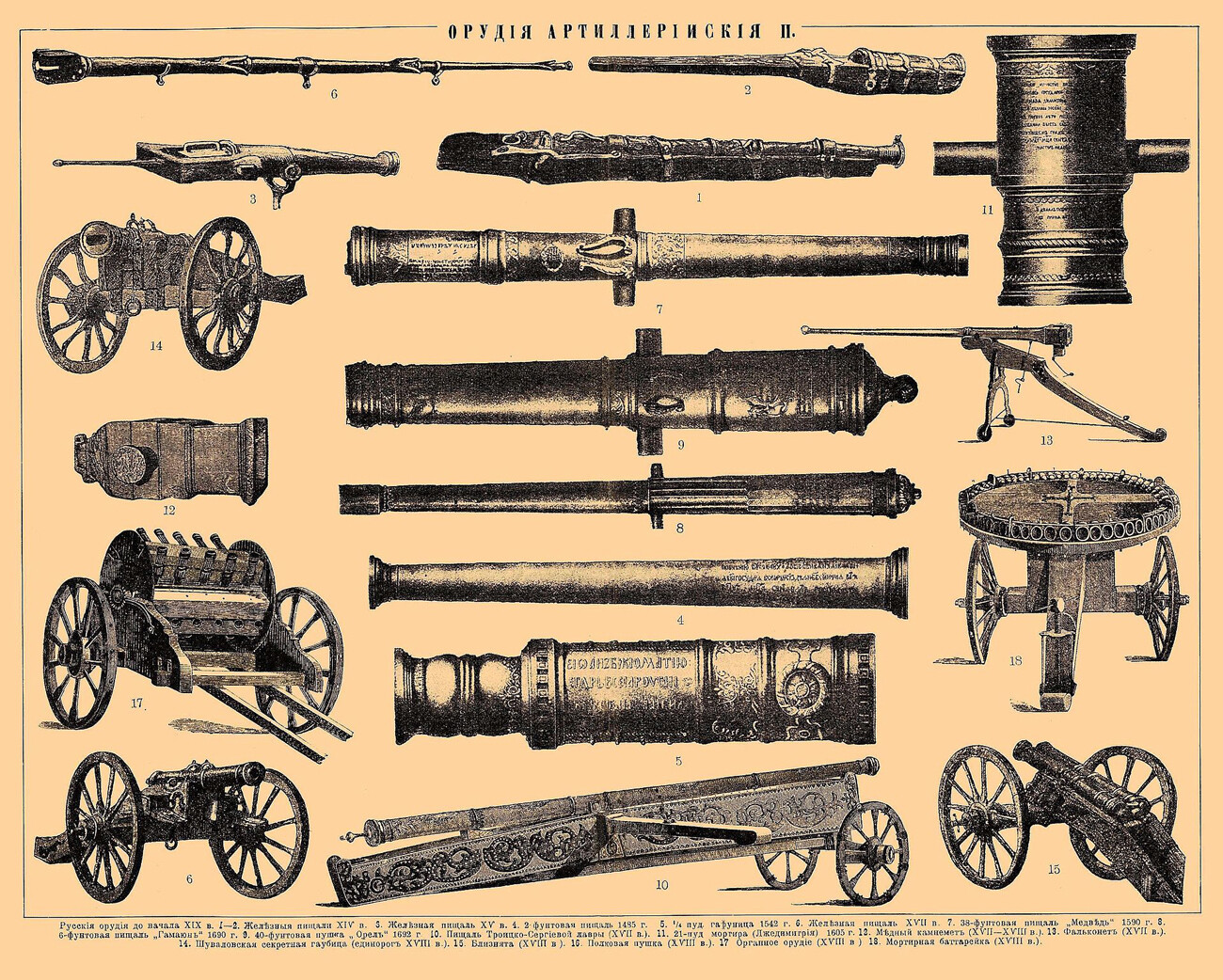

Various artillery guns, an illustration from Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary

Public DomainHow did criminals manage to terrorize the population even in the middle of the 18th century? The first police began to appear in the 1730s, but only in large cities. Professional military men, mostly from the nobility, often did their service in large cities or somewhere far away on the battlefield. Regional governors had a limited arsenal and a small number of people – permanent military garrisons were only in large cities. In addition, to take decisive action the local administrator needed permission from the central authorities. Marauders were well organized, knew the local terrain and local inhabitants, and knew the local garrisons. Among the ranks of the bandits often were many runaway peasants and renegade soldiers.

Therefore, a traveling merchant always had to worry that marauders were waiting in any thick bush or densely wooded area. The protection of one's goods and property was purely a personal responsibility. In short, you were on your own.

"Runaway," 1883, by Konstantin Savitsky

Tretyakov gallery/Public DomainCenturies ago, every wealthy man had an entire arsenal of cold weapons and firearms. The estates of the rich were well protected and fortified: the Ranenburg Estate that was owned by Prince Alexander Menshikov had ramparts, gates and bastions on which cannons were positioned. Average people naturally had much simpler weapons.

In 1721, Prince Gagarin in Tula province had a smoothbore gun and a saber. In the attic of an estate house that belonged to commissioner Pashkov in Kolomna in 1723, two guns and two "small iron cannons” were found. A clerk named Losev in the Ruza Region had three iron cannons. At that time, cannonballs and gunpowder were freely sold. So, the average man could have an imposing arsenal at home if he could afford it.

The estate of Prince Grigory Volkonsky, a close associate of Tsar Peter and director of the Tula Gun Factory, had 14 cast-iron cannons, two cannons of red iron and 16 gun carriages, including four on wheels. The arsenal, however, didn’t help the prince – Peter the Great had him executed for theft during the construction of a factory.

READ MORE:Why there was always a shortage of executioners in Russia?

"Sentries on the border of the Moscow state," 1907

Public DomainEven at the end of the 18th century, marauders remained a problem for common people. Poet Mikhail Dmitriev recalled: "With the onset of each summer, when the forests were already covered with thick green, the robbers appeared... My grandfather was always ready: every year with the onset of spring, in his village house on the walls of the hall and front were hung rifles, bags with charges, swords and darts."

When the bandits approached, the village peasants ran to their master's yard, and the house servants took up arms. Dmitriev himself witnessed one encounter between his grandfather and some marauders: "My grandfather wielded his dirk [a type of knife], ordered us to open the gate, and waited for the robbers on the porch. This time, however, it turned out well. The robbers, twelve in number, armed from head to foot, rode up in their horses to the roundabout, called the watchman and told him: ‘Go and tell Ivan Gavrilovich, that we would not be afraid of his dirk, it’s just that our horses have become tired.’”

On the same day, however, the same gang of bandits looted and burned the mill near the town of Syzran.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox