Portrait of Grand Duchess Alexandra Fedorovna with her children — Grand Duke Alexander Nikolaevich and Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna. 1821-1824, George Dawe

Russian MuseumIn 1669, the 45-year-old Maria Miloslavskaya died five days after her last child was born; her infant daughter Yevdokia also died. That was her thirteenth childbirth. Before the era of Peter the Great, the wives of Russia’s rulers gave birth very often – nearly every year – and not all children survived. Of course, the health of these women suffered from such frequent births.

Across the centuries, both Moscow tsarinas and St. Petersburg empresses had similar and natural problems linked to childbirth. Even after Russia entered the modern era with Peter the Great, the country’s empresses also were expected to bear many children. In 1832, doctors prohibited Empress Alexandra, the spouse of Emperor Nicholas I, from having sexual relations with him. Their son Mikhail, born in 1832, was their seventh child, and the 34-year-old empress’ frail health wasn’t sufficient enough to withstand another pregnancy.

Grand Duke Constantin Nikolaevich (son of Nicholas I) as a child, 1820s, Petr Sokolov

Public DomainUnlike in Europe, where royal childbirths were semi-public events (for the court) since the Middle Ages, with most high nobility in attendance, Russia had a tradition that made sure everything was much more private. Nevertheless, during the St. Petersburg imperial period, the childbirths of royal ladies were attended not just by their husbands but also by their fathers-in-law. For example, in 1714, Peter the Great attended the childbirth of Charlotte Christine Sophie, the wife of Tsarevich Alexey.

The birth of Pavel Petrovich was attended by the spouse of his mother, Grand Duchess Yekaterina Alexeevna (future Catherine the Great), Grand Duke Peter Fyodorovich, and Empress Elizaveta Petrovna. Unlike the child births of the Moscow tsarinas, where the expecting young mother was surrounded by warmth and care before and after the birth of her children, unpleasant incidents sometimes took place during the imperial era.

Grand Duchess Yekaterina Alexeevna, while giving birth to Pavel, was literally abandoned for several hours. “Right after he was swaddled, the Empress brought in her priest, who gave the child the name Pavel; immediately after, the Empress ordered the midwife to take the child and follow her,” Catherine the Great wrote in her memoirs.

Alexey Bobrinsky as a child, 1760s, Fedor Rokotov. Alexey Bobrinsky was Catherine the Great's bastard, his father was Prince Grigory Orlov

Russian Museum“As soon as the Empress left,” Catherine continued, “the Grand Duke also went to his chambers, and I saw no one right until three o'clock (the childbirth happened at about noon – RB). I was sweating really hard; I asked lady Vladislavova to change my clothes and my sheets, but she replied that she wouldn’t dare do it. Several times I asked for the midwife, but she wouldn’t come. I asked for some water, but received the same reply.”

Catherine the Great saw her son Pavel for the first time in only 40 days (!) after his birth, and even then, it was just for several minutes. However, many years later, Catherine would in the same manner take her newborn grandsons Alexander and Konstantin from her daughter-in-law, Maria Feodorovna.

To the contrary, Nicholas I was an example of a tender husband and father who attended all the childbirths of his wife; even holding his wife, the future Empress Alexandra, by her hand despite being exceedingly worried.

“I have a headache and my heart hurts, I feel ill,” the future Emperor Nicholas I wrote after the successful childbirth of his daughter Alexandra in 1822; (when his daughter Olga was born, Nicholas wrote: “the small one screams like a frog.”) Doctors gave Nicholas an emetic and he vomited four times. He attended all of his wife’s subsequent childbirths, also keeping her company afterwards.

Emperor Nicholas I and Empress Alexandra Fedorovna, 1830s, Franz Krueger

Russian MuseumIn subsequent years, emperors also attended the childbirths of their wives and daughters-in-law. In 1868, the ruling Emperor Alexander II and his wife attended the childbirth of Maria Feodorovna, the wife of their son, the heir, the future Alexander III. The Emperor and his son held Maria by the hand from both sides at the moment when the future Emperor Nicholas II was coming into this world. “God has sent us a son, and we called him Nicholas. It’s impossible to imagine how much of a cheerful occasion this was; I hugged my lovely wife, who cheered up immediately and was extremely happy. I cried like a child,” the future Emperor Alexander III wrote in his diary.

It’s important to note, however, that Maria Feodorovna wasn’t at all happy that her father-in-law attended the birth of her son Nicholas. The presence of her father-in-law, as Zimin wrote, citing the diary of the Grand Duchess, “embarrassed her very much.”

Later, she tried not to inform anyone of the next approaching childbirth. On November 22, 1878, when about to give birth, she managed to stoically sit through a lunch with the Emperor Alexander II in attendance: “the pains continue and become more frequent,” she wrote to her mother that day, “I only wish I can hold on while he’s still here!” An hour and a half after the lunch ended and the Emperor departed, Maria gave birth to her third son – Grand Duke Mikhail.

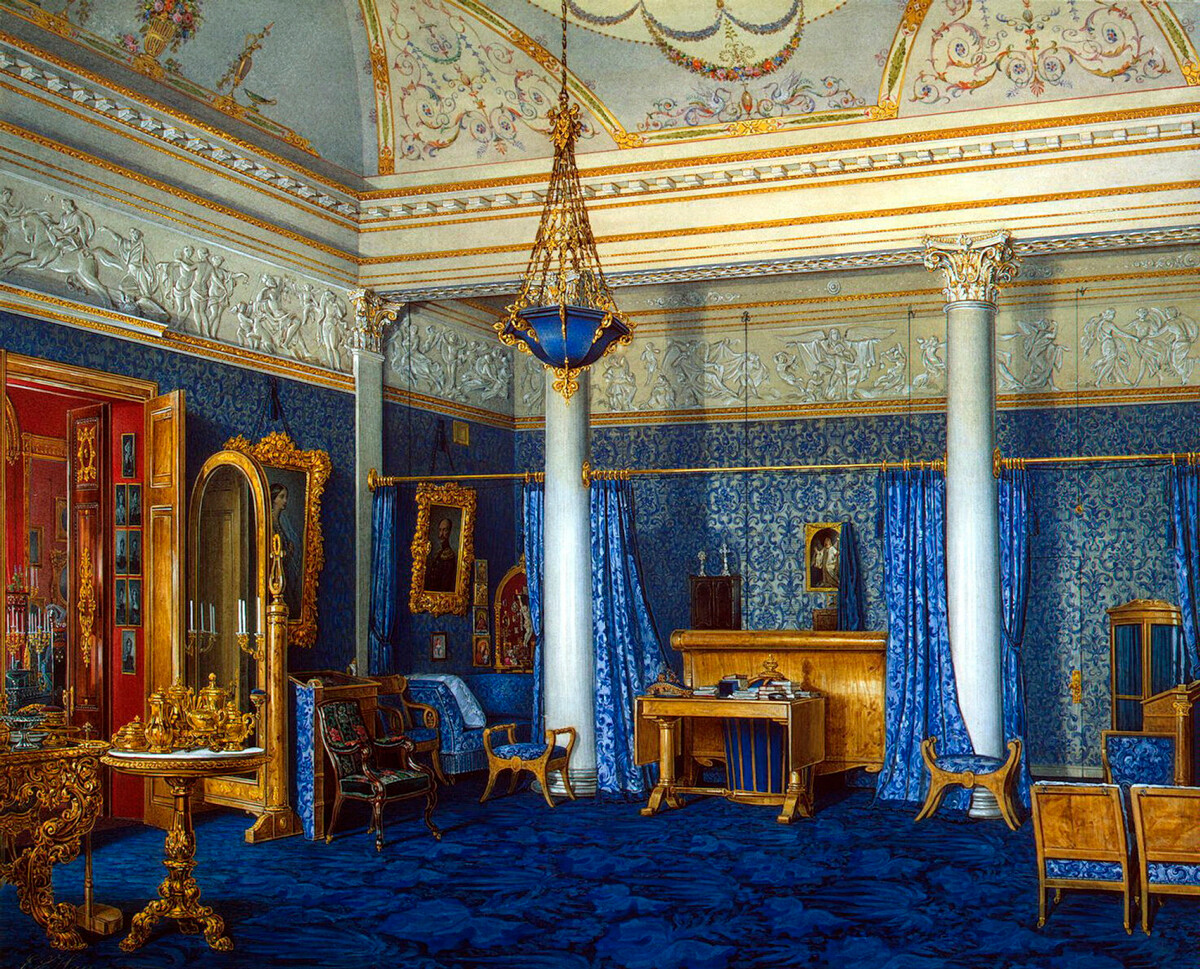

Empress Alexandra Fedorovna's bedroom in the Winter Palace, Eduard Hau

Public DomainApart from the mandatory presence of the husband and the ruling monarch, the Romanovs observed several more household traditions.

There was an important custom observed ever since the times of the Tsardom of Muscovy: after the birth of a royal child, the husband generously rewarded his wife. In the above-mentioned birth of 1822 the exhausted Nicholas presented his wife with a turquoise diadem adorned with pear-shaped pearls. However, he went one step further and also planted an “oak for Olga” in the garden of the Anichkov Palace, as historian Igor Zimin wrote.

Another tradition was described by Grand Duke Alexander “Sandro” Mikhailovich: “Every time, during childbirth, I thought it to be my duty to follow an ancient Russian tradition. It states that, after the first cry of a child, the father has to light two candles, which he and his wife had held during their wedding ceremony in church; then he has to swaddle the newborn into the shirt he wore the previous night.”

Also, as Zimin writes, there was a tradition to prepare everything that the newborn needed a long time before his birth. However, the sheets, the sleeping suits and caps were stored in specially sealed chests, and then kept far from the residence where the future birth of a tsarevich or tsarevna would take place. This was done in order not to jinx it.

Grand Duke Nicholas (future Nicholas II) with his mother Maria Fedorovna, born Dagmar of Denmark, 1870, Sergey Levitsky

Public DomainEvery pregnancy of any reigning empress was reported in the official Pravitelstvenniy Vestnik (Government Gazette); and the course of the pregnancy was closely monitored by royal obstetricians. As the time of childbirth approached, doctors and the midwife moved closer to the empress, into the residence where she prepared to give birth.

Professional royal obstetricians and midwives, who usually were from overseas, delivered the baby, as was the tradition from the time of Peter the Great. Starting in 1798, the St. Petersburg’s Medical-Surgical Academy had its own “Department of Midwifery”. By 1843, the staff of the Court Medical Unit had four midwives and a royal obstetrician.

Alexander III with his wife and children, 1870, Sergey Levitsky

Public DomainAlmost all midwives who served the imperial family in the 19th century were German. The most famous is widely considered to be Lady Hesse, who assisted with the births of all of Nicholas I’s children. Royal obstetricians and midwives received not just a salary but also gifts and payments for every successful childbirth – colossal payments of thousands of rubles; (back then, a state minister would receive about 5,000 rubles per year).

All empresses and grand duchesses gave birth at home – in one of the royal residences. Almost all members of the imperial family after the rule of Peter the Great were born in St. Petersburg or its surroundings; only the parents of Alexander II went to Moscow to see their son enter this world – as requested by Emperor Alexander I. Nicholas and Alexandra fulfilled his wish, and the emperor liberator who gave freedom to the serfs arrived in this world in the Chudov Monastery in the Kremlin.

No special chairs or seats were used for childbirth – all empresses gave birth right in their beds. However, starting in the middle of the 19th century, royal women giving birth were given medication to mitigate the pain. “To ease her childbirth suffering, the court doctor usually gave her a small dose of chloroform,” Sandro wrote.

In the 19th century, following childbirth, no one thought of leaving a grand duchess alone, not to mention an empress. During her postpartum period, the medics and the midwife continued to stay with and monitor the imperial mother who just gave birth, until the moment she would fully recover.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox