“With all my courage, I could not withstand the terrible glare of his left eye, from which the end of a red-hot nail shone brightly and burned through my eyes…" – Vasiliy Mitrofanov, who once served as an orderly for Emperor Nicholas I, remembered staring the Emperor in the eye. "Until my death, I will not forget its penetrating brilliance, which can embarrass even people such as I, who do not belong to the cowardly lot.” Ekaterina Junge, daughter of painter Fyodor Tolstoy, remembered that “the Emperor’s stare, as the talk went, could kill people instantly”. Who was the man behind this deathly stare?

Nicholas I and his son, Grand Prince Alexander Nikolaevich, at an artists' studio, 1854, by Bogdan Villevalde, 1884.

Bogdan Villevalde/Russian State MuseumAfter Peter the Great, who was 204.5 cm in height, Nicholas I was considered the second-tallest Russian emperor. We know that from a story recorded by Russian writer Xenofont Polevoy. After a play in which Russian actor Vasiliy Karatygin played Peter the Great, Nicholas compared his own height to Karatygin’s and said the actor was taller than himself: the Emperor was 189 cm tall. “A high forehead, eyes full of fire and majesty, a mouth with a somewhat sarcastic expression, a heroic chest, colossal height and, finally, a majestic gait gave the sovereign something extraordinary in appearance,” Count de Passi, a contemporary, wrote.

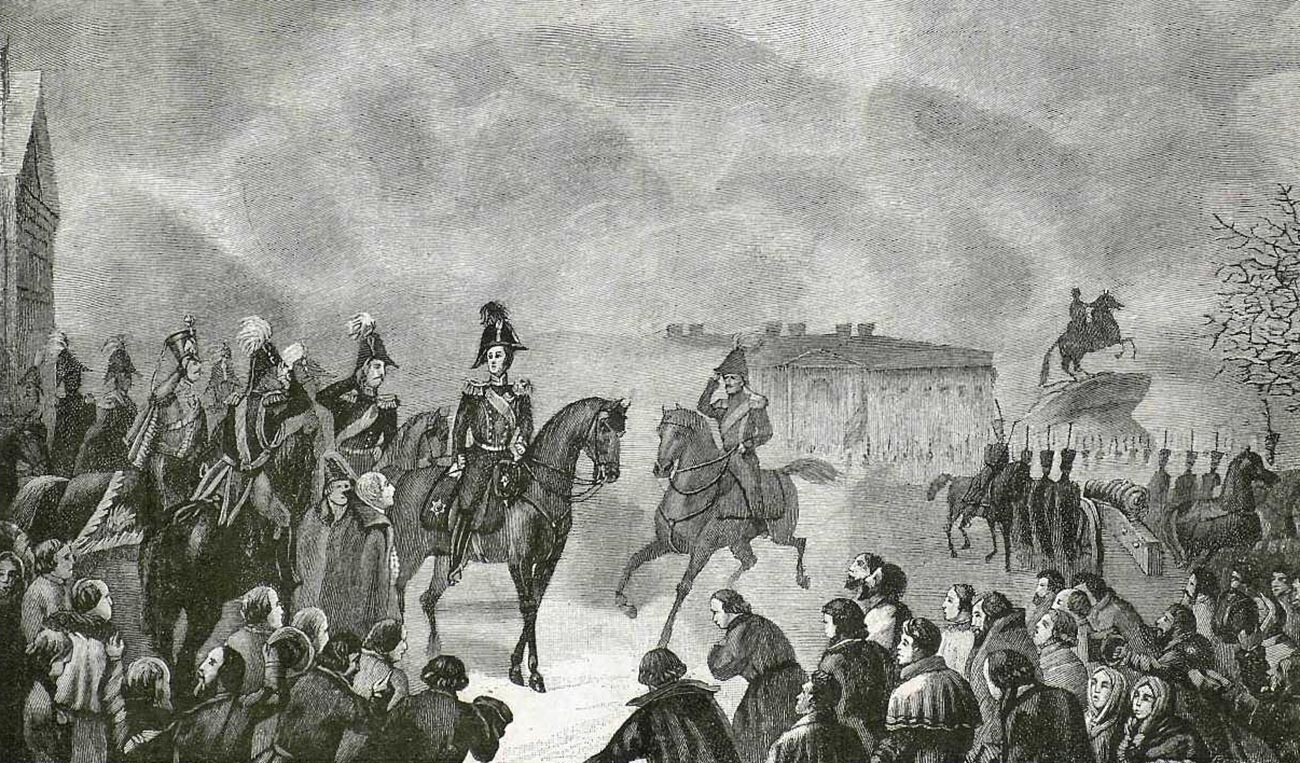

Emperor Nicholas I on the Senate Square in St. Petersburg during the Decembrists' Revolt, December 14th, 1825

Public domainNicholas I’s reign started in a turmoil – the Decembrists’ revolt, which sought to overthrow the Romanov rule and install a republican form of government in Russia. The revolt was ignited by a few young officials and military men belonging to the state’s elite. However, the Emperor firmly protected the monarchy and suppressed the revolt using his loyal military. But, Emperor Nicholas was far from delighted that he had to start his reign with a bloodshed. “I am the emperor, but at what price, my God! At the cost of the blood of my subjects,” Nicholas wrote to his brother Constantine.

The Nikolaevsky Railway station in St. Petersburg

August PetzoldUnder Nicholas I’s reign, the first Russian passenger railway, from Moscow to St. Petersburg, was constructed and it was Nicholas I who defined the width of the Russian railroad track, making it 1,524 mm (while in Europe, it was 1,435). This decision made by Nicholas had long-lasting consequences – thanks to it, European enemies of Russia couldn’t readily transport their military by railroads into the Russian mainland, as the track width was different. To this day, trains have to change their wheel base on the Russian border to continue to their destination.

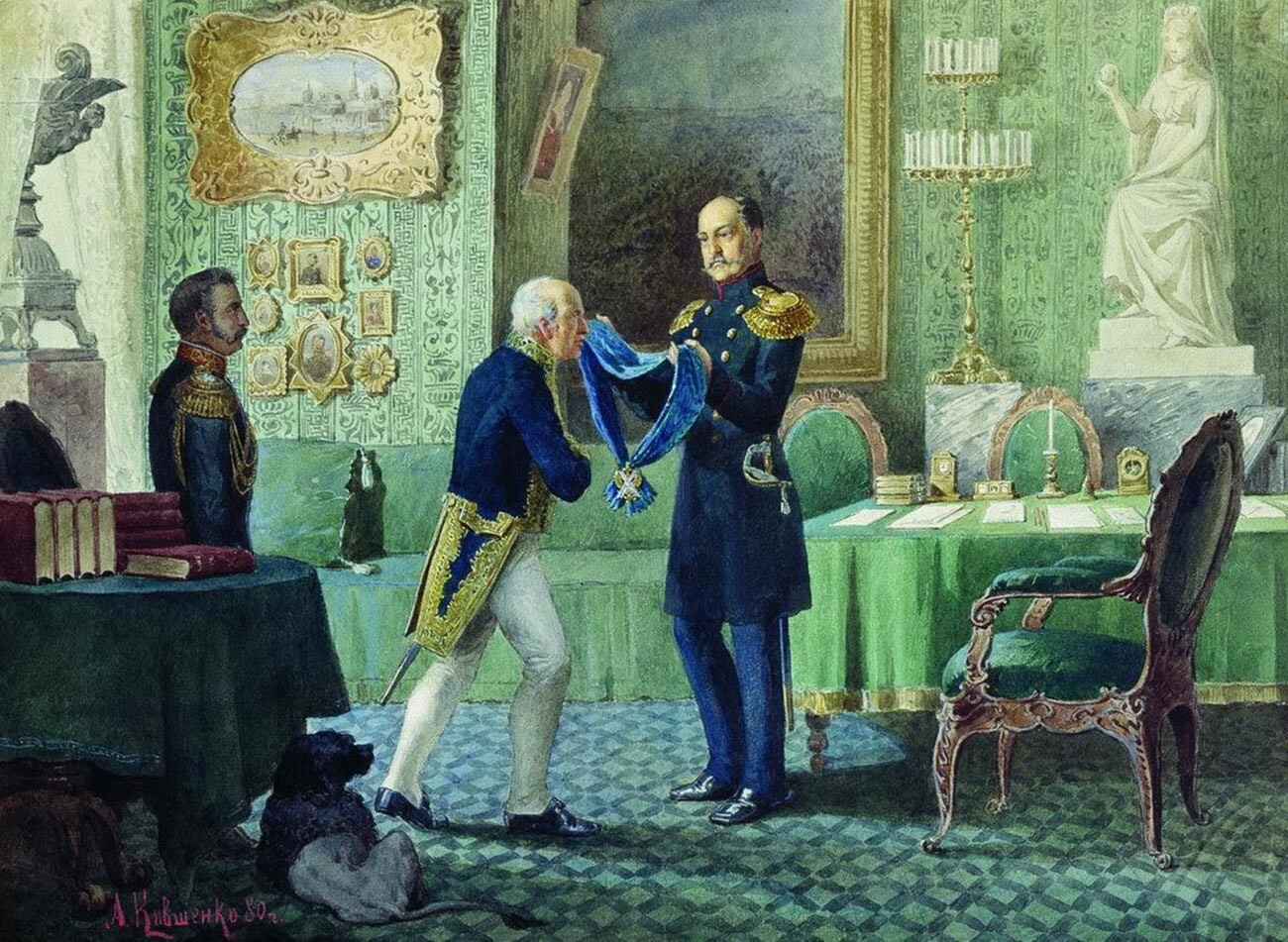

Emperor Nicholas I, decorating Mikhail Speransky with the Order of St. Andrew

Alexey KivshenkoBy 1825, when Nicholas I had become emperor, Russian law and government system was in a poor state: some laws, even from a century ago, from the times of Peter the Great, were still active, along with many others, which created chaos in the law sphere. Nicholas I ordered Mikhail Speransky, the leading statesman of his time, to perform a codification of laws, which was completed by the 1830s. The 46-volume ‘Complete Collection of Laws of the Russian Empire’ comprised all laws chronologically and the ‘Digest of Laws of the Russian Empire’ was the code of active penal and civil laws. For the work on the codification of Russian laws, Speransky was awarded the highest state decoration, the Order of St. Andrew.

Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna

Franz Kruger/State Russian MuseumNicholas I came off as a fierce and demanding sovereign to his subjects, but he was an all-forgiving and loving father for his family. Maria Fredericks, the lady-in-waiting at the court, remembered: “Emperor Nikolai Pavlovich was the most gentle father of the family, cheerful, joking, forgetting everything serious to spend a quiet hour among his beloved wife, children and, later, grandchildren.” However, his children weren’t spoiled and were brought up in relative austerity. They played in open air when they liked to, no matter what the weather was, learned rowing from a sailor, both boys and girls. As for his sons, Nicholas brought them up in military style, taking them to drills and maneuvers with other young cadets, not giving the princes any preferences.

Varvara Nelidova

Public domainHowever, later in life, Nicholas and his wife slowly drifted apart – after giving birth to seven children, Empress Alexandra became ill and the doctors recommended her long vacations. By this time, the emperor was known to have another favorite, Varvara Nelidova. “The tsar is more and more busy with Nelidova every day. He goes to her several times a day. He tries to be near her at the ball all the time. The poor Empress sees all this and bears it with dignity, but how should she suffer,” Maria Nesselrode, a lady-in-waiting, wrote.

Nicholas I at a construction site

Mikhail ZichiOne of the goals of the Decembrists’ revolt was the abolition of serfdom in Russia. Nicholas I, however, also understood that serfdom hindered the development of the country. Under his reign, a Secret Committee was formed, that discussed the possibility of the abolishment of serfdom. Even in 1855, a month before his death, Nicholas told his statesman Dmitry Bludov that he didn’t want to die until the serfs were free; however, he only wanted to free the serfs if they retained their land property. “Only then I would be happy, when these people are freed from serfdom,” Nicholas told Alexandra Smirnova-Rosset.

Unfortunately, Nicholas I didn’t manage to free the serfs during his lifetime. However, under him, it was forbidden for the serf owners to sell their serfs without land and the serfs were allowed to bail themselves out of serfdom, if their landlord’s manor was being sold for debts. When Alexander II finally freed the serfs in 1861, he and his statesmen used the data and law drafts that had been prepared under Nicholas I.

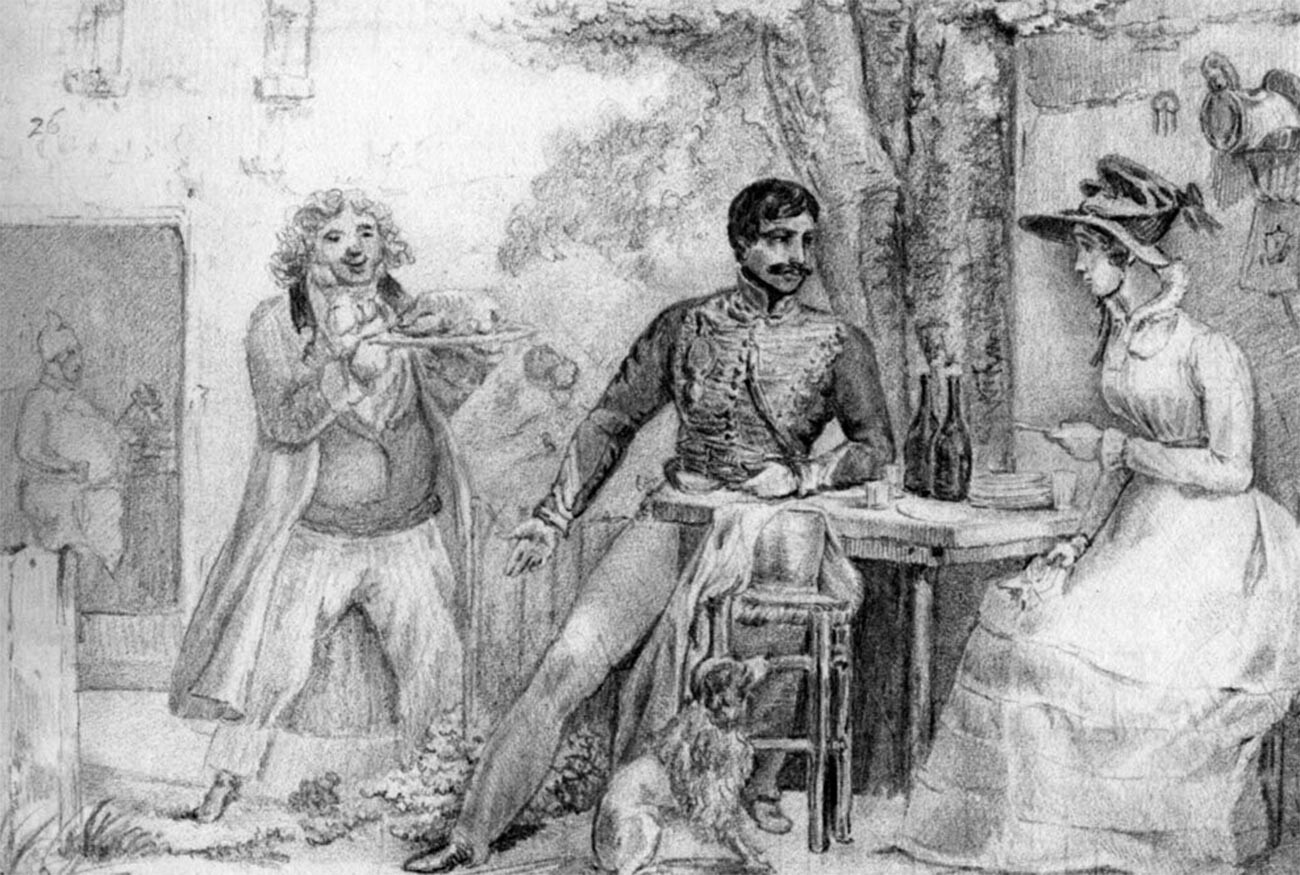

"In a canteen", drawing by Nicholas I

Public domainIn between all the important matters the emperor had to attend to, he always found time to practice music or painting. In his youth, Nicholas received education as a military engineer, which involved a great lot of drawing – bridges, cannons, maps, etc. This is why Nicholas became a good artist. He also liked music and played a variety of brass instruments, inspiring, in particular, his grandson, the future Emperor Alexander III, to learn the trumpet, as well.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox