Georgy Malenkov as the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR

Sputnik‘And Shepilov, who joined them’ – In Soviet times, every citizen knew this phrase. It’s linked to the case of the ‘Anti-Party Group’, which led to Georgy Malenkov’s removal from the highest party positions. Malenkov decided not to argue with the decisions of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union bigwigs. First, he was “transferred” to the position of the director of the Ust-Kamenogorsk Hydroelectric Plant, then – to a similar position in the faraway Ekibastuz in Kazakhstan. In 1961, Malenkov was even expelled outright from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Malenkov with his wife Valentina

Archive photoOnly ten years later, the former Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union was allowed to return to Moscow. With his wife, Valeriya Golubtsova, he lived in a two-room apartment at 2 Sinichkina Street, in a back corner of the Lefortovo District, near a railway station, a cemetery and the Lefortovo Prison.

“He didn’t offer his memoirs to magazines, didn’t haunt the reading rooms of Moscow’s libraries. So, we can, therefore, assume that he had decided not to write down his memories,” historian Roy Medvedev wrote. “Before, he was only moving around Moscow and its suburbs in an armored limo. Now, he had to buy tickets for a regular suburban train. He was silent during these rides; sometimes, he exchanged a couple of words with his wife. Malenkov lost a lot of weight, so even his former colleagues didn’t always recognize him. Every summer, Malenkov rested and went through treatment at privileged sanatoriums.”

Georgy Malenkov after 1957

Archive photoThere were rumors that Malenkov had often been seen in a church in Kratovo, where he had a dacha. A nobleman by birth, he remained religious until the end of his life. In 1980, by the order of Yuri Andropov, Malenkov and his wife were moved to Frunzenskaya Embankment, to a ‘nomenclature’ apartment, where he died in 1988, outliving his wife by only three months.

Nikita Khrushchev at his dacha

SputnikNikita Khrushchev was ousted from the position of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, after he was called back to Moscow from his vacation in Pitsunda, Crimea. At a Presidium meeting led by Leonid Brezhnev, Nikita Sergeyevich was so viciously “thrashed” that, as his son Sergei remembered, “his facial features grew haggard overnight, he turned gray somehow, his movements grew slower.” The next morning, on October 15, 1964, Khrushchev was “injured in privileges”: his access to government telephones was canceled, his personal guard was changed for a lower-ranked one: now, they were simply “watching over” him.

Nikita Khrushchev at a vacation.

Boris Kosarev/russiainphoto.ruAnd yet, the Party was more lenient with Khrushchev than with Malenkov. He was evicted from a government dacha in Gorki, but he retained his bungalo dacha in Petrovo-Dalnee and his five-room apartment on Arbat Street; He and his family were still allocated servants. However, Khrushchev practically lived under house arrest and only left it to go to clinics for check-ups.

Former Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev is seated with his wife Nina Petrovna at their dacha in Moscow in 1965

APAccording to the recollections of his relatives, the ex-leader fell into depression. As historian William Taubman writes: “Khrushchev found no joy in neither books nor movies, with which his children tried to cheer him up.” His son and wife claimed that he often cried for long periods of time and wandered his dacha plot and its vicinity in silence instead of doing anything – of course, always under the surveillance of KGB agents. “Sometimes, he broke his silence and, with bitterness, repeated that his life was over, that he was alive while people needed him, but now his life had become meaningless. At times, tears appeared in his eyes,” his son Sergei Khrushchev remembered.

Later, Khrushchev was moved to reside in his Petrovo-Dalnee dacha on the Istra River bank. From Summer 1965 onward, he began having more walks and conversations with the vacationers of the nearby sanatorium, which were allowed and overseen by the state security. “The village administration decided to make a gate in the fence [of his dacha] and now the vacationers constantly flocked around Khrushchev, took photos with him and listened to his stories.

READ MORE: Khrushchev never banged his shoe at the U.N.

Nikita Khrushchev in the Moscow Kremlin with his daughter-in-law and grandchildren

Dmitry Baltermants/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruSlowly, such ‘meetups with Khrushchev’ became an unofficial, but necessary part of the local ‘cultural program’,” William Taubman wrote. Khrushchev was almost indifferent to the remnants of his “past life”. An avid hunter in the past, he gave away all his guns; he almost never replied to the manifold of letters he received. Sometimes, he was visited by “approved” guests – poets Yevgeny Yevtushenko, Vladimir Vysotsky, director Roman Karmen, playwright Mikhail Shatrov, to name a few.

Khrushchev also became fascinated with gardening – he grew potatoes, cucumbers, radishes, pumpkins and corn; he built greenhouses by himself and weeded the patches. From 1967, he began dictating memoirs, which were later brought to the West and published in English. Only the first volume of his memoirs was released while Khrushchev was alive – on September 11, 1971; he died from a heart attack at the age of 77.

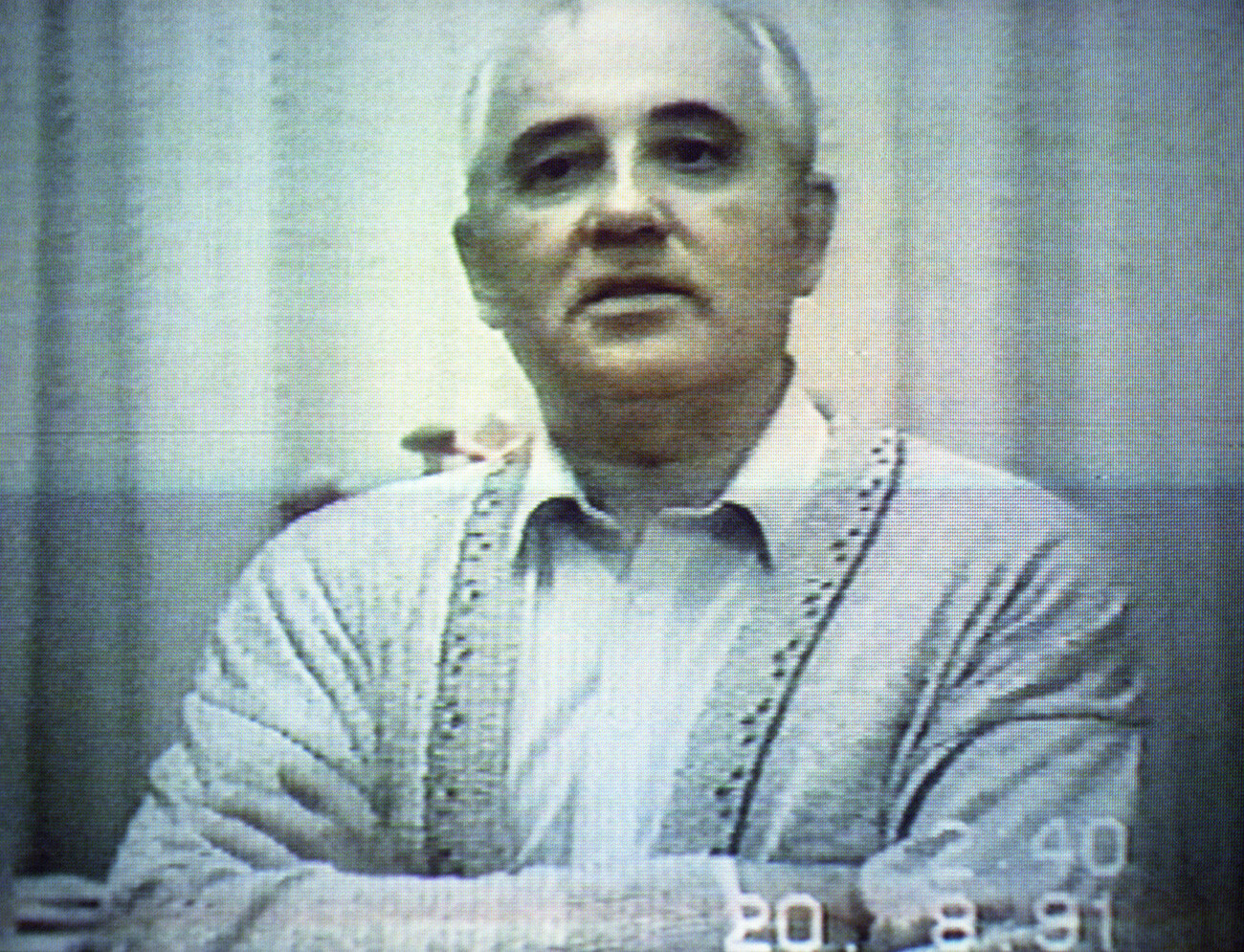

A frame from the video message of the President of the USSR Mikhail Gorbachev to the people, recorded on August 20, 1991 during his house arrest at his dacha in Foros.

Yuri Abramochkin/SputnikMikhail Gorbachev was removed from power almost in the same way as Nikita Khrushchev. During the August Coup of 1991, he was at his dacha in Foros in Crimea and didn’t fly to Moscow. Later, Gorbachev himself claimed that he was “isolated”, but that doesn’t coincide with the statements of other people. On August 24, 1991, after the end of the coup, Gorbachev announced his resignation from the position of the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union; on December 25, he resigned from the position of the President of the USSR, transferring his position to the president of the Russian Federation – Boris Yeltsin.

Mikhail Gorbachev (left) is an honorary guest of the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall – and Berlin Mayor Klaus Wowereit.

Igor Zarembo/SputnikGorbachev didn’t leave his political and public work. In December 1991, right during the events associated with the collapse of the USSR, he founded and headed ‘The Gorbachev Foundation’, a non-profit organization for economic and political research. Gorbachev tried to influence politics – he financed the Social Democratic Party of Russia, made statements that condemned the policy of Yeltsin, but he couldn’t provoke a scandal. To the contrary, in 1994, Yeltsin gave him a lifelong pension equal to 40 minimum old-age pensions annually. However, in the 1990s and 2000s, Gorbachev didn’t live in Russia, choosing Rottach-Egern (Bavaria) as his place of residence.

In 1996, he ran for president of the Russian Federation and even received more than 380,000 votes (0.51%). The following year, however, Gorbachev became famous worldwide, after starring in a Pizza Hut commercial. In 2011, on his 80th birthday, by the decree of then President Dmitry Medvedev, he was awarded the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-Called, the highest order conferred by the Russian Federation. It’s interesting that Gorbachev celebrated his 80th birthday both in Russia and in London – with the charity concert ‘Gorby 80 Gala’ at Royal Albert Hall on March 30, 2011.

Gorbachev died in Moscow on August 30, 2022. Unlike Malenkov and Khrushchev, Gorbachev was buried with military honors and with a ceremony, arranged in the Pillar Hall of the House of the Unions.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox