Olya Sharkova, horn player, 1974

Yuri Somov/Sputnik

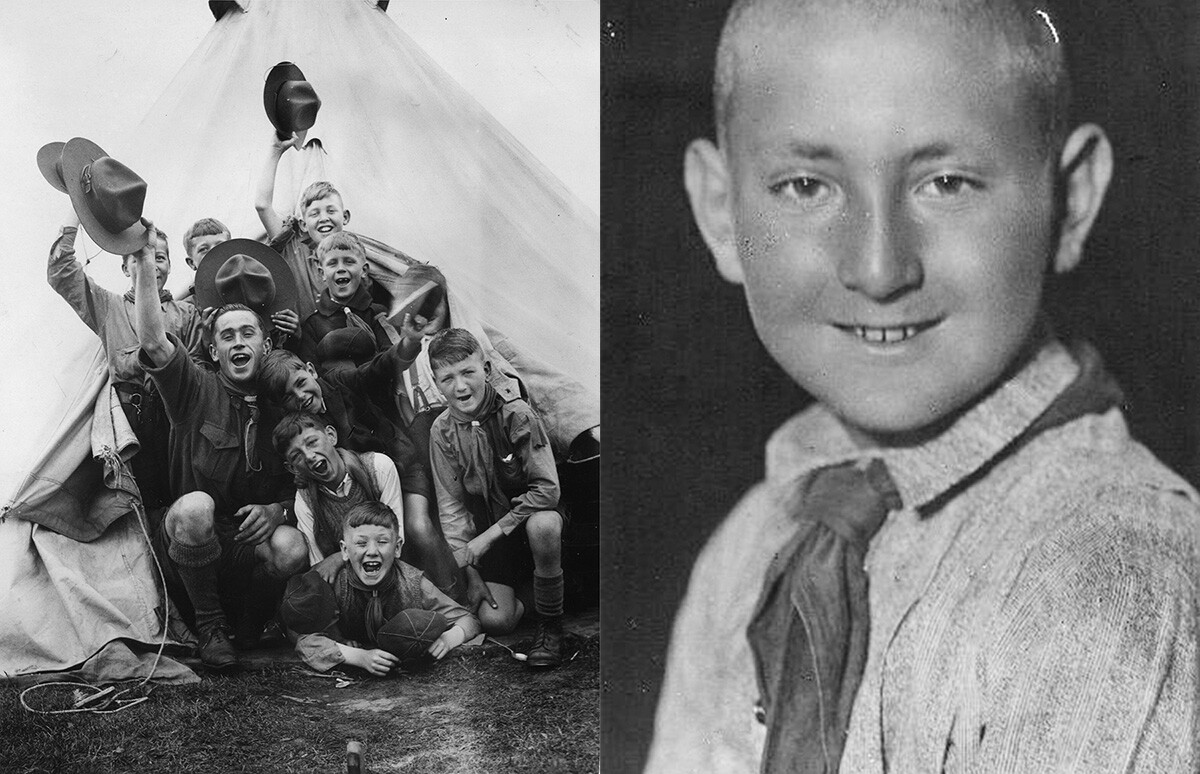

11th August 1938: Members of a scout group camping (L) An unknown pioneer in 1929 (R)

Richards/Fox Photos/Getty Images; МАММ/MDFThe Boy Scout movement appeared in Russia before the Pioneers – under the tsars, in the late 1910s – but, its development was hindered by the revolution. In the 1920s, Soviet authorities decided that it was necessary to work separately with youth. The first to talk about the creation of a youth organization was Nadezhda Krupskaya, who in 1921 made a report "On Boy Scouts".

When, in 1922, the ‘pioneer’ movement was created, they really borrowed a lot from the scouts: the bugle, drum, greeting ("salute"), the scout motto "Be ready!" and the answer to it: "Always ready!", the organization of detachments and the tradition of gatherings around the campfire, while the green neck scarf of scouts in the USSR turned into a pioneer tie – a scarlet (the color of the fire of the world revolution), isosceles triangle with a length of 100 cm and a width of 30 cm.

An induction to Pioneers on Red Square in Moscow, 1974.

Boris Kavashkin/SputnikBoth the scout handkerchief and the pioneer tie are triangular. If the scouts symbolized three roads – to themselves, to people and to God, then it was accepted that the three corners of the pioneer tie were the three generations of the socialist people: pioneers, Komsomol members and communists.

An induction ceremony in Moscow, 1974

Vladimir Minkevich/SputnikSoviet children were accustomed to rituals from a young age – before they became pioneers, they were "Octoberists". To become a pioneer, you had to learn the pioneer oath by heart and study more or less well. Pioneers were accepted at a ceremony held in the school assembly hall or a place otherwise known as "Lenin's corner," in one of the school rooms. At the end of the ceremony, a tie was solemnly placed on the pioneer.

The tie, which was worn around the neck, can be likened, in this sense, to a cross, which the Soviet government had "canceled". The tie was considered sacred for a pioneer; it had to be taken care of, washed, ironed and stitched.

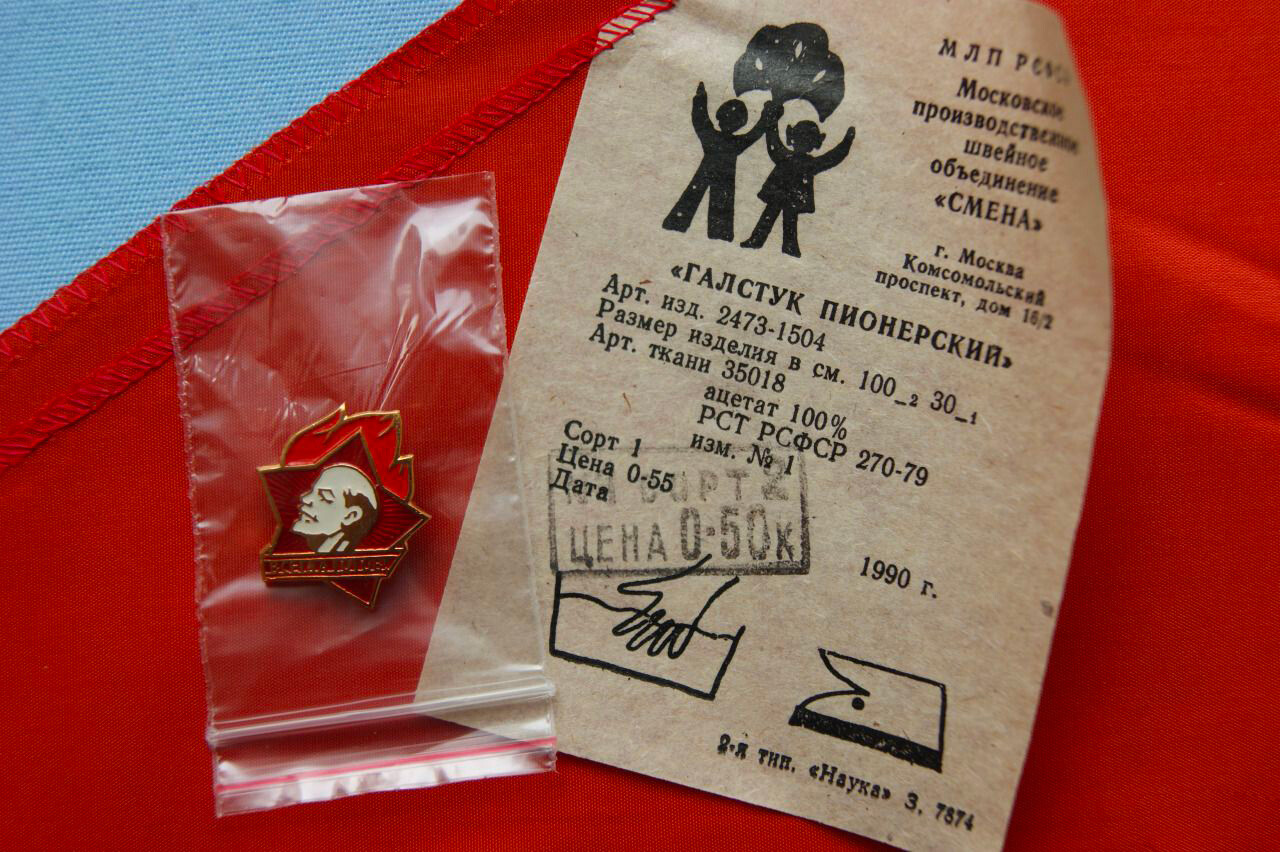

A Pioneer necktie with a Pioneer badge and a price ticket

Avito.ruPioneer ties in the USSR were not standardized by material, they were produced by several different companies. The most popular one was made of acetate silk by hot cutting – it was not stitched, but melted at the edges and quickly began to unravel.

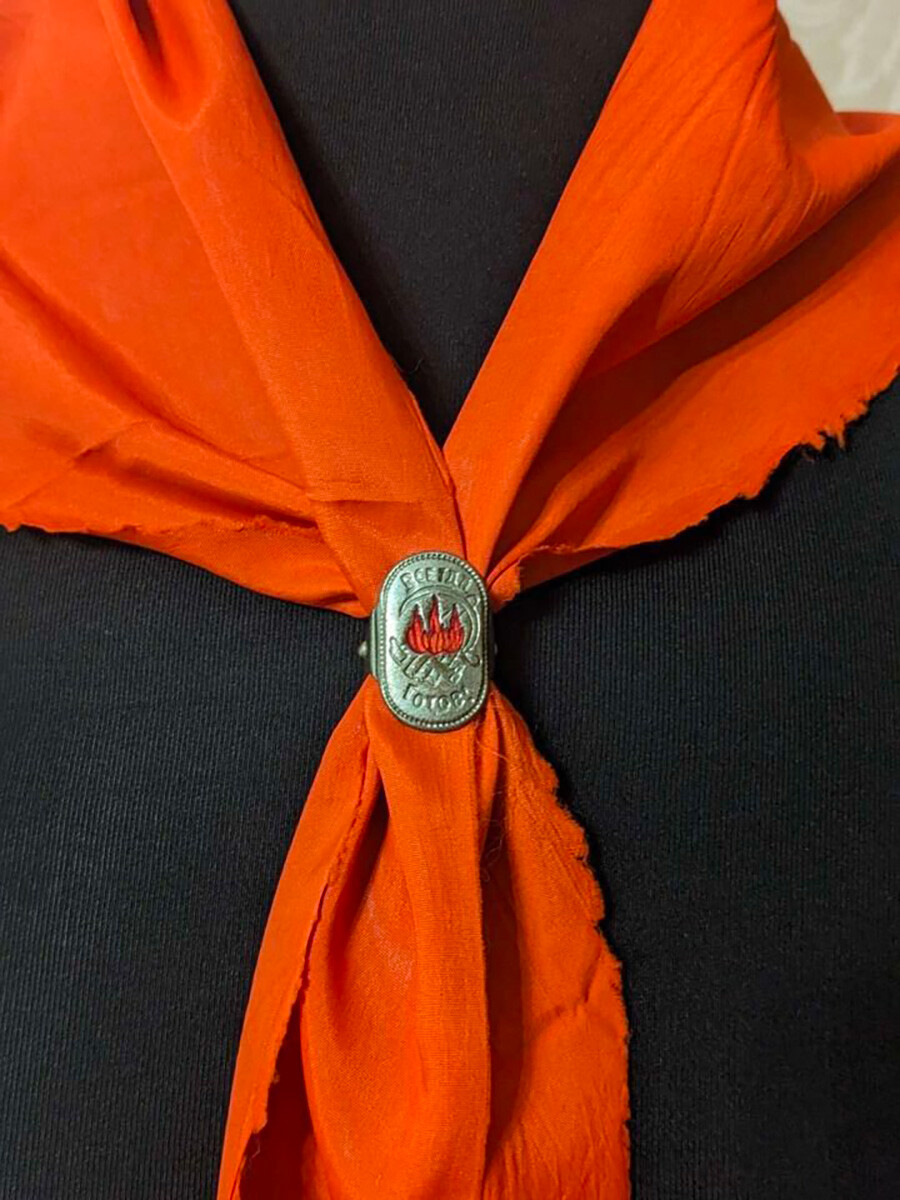

A ragged Pioneer necktie

Avito.ruIf the tie was in disrepair or lost, he had to change it at his own expense and often in secret from everyone – senior pioneers and counselors, learning about the loss of the tie could accuse the schoolboy of disrespect for pioneer symbols and this could lead to serious trouble. The pioneer was called to a meeting, where he was "roasted" – asked how well he was studying, checked whether he was participating in pioneer work enough and so on.

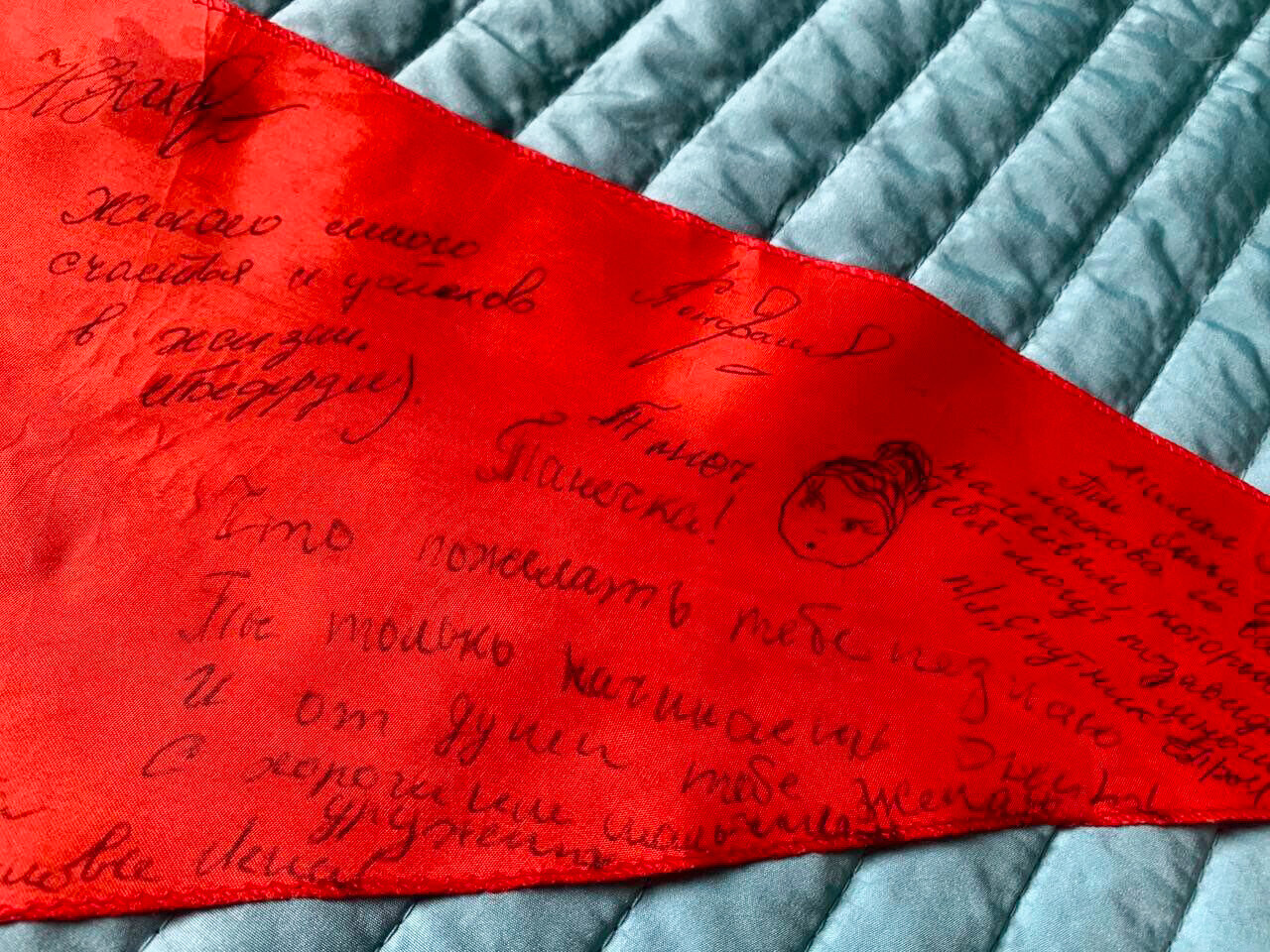

A pioneer necktie of a girl named Tanya covered in best wishes and autographs of friends

Avito.ruIt was allowed to "spoil" a pioneer tie only in one case – on the day of departure from the pioneer camp. New friends from different pioneer groups, having met in the camp, would write wishes and greetings to each other on the ties, often signing and drawing suns and hearts. Such a tie, of course, was kept as memorabilia for many years.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox