"Teatime" by Konstantin Makovsky

Ulyanovsk Regional Art Museum

"Peasant Woman of Tver Province", 1840, by Аlexey Venetsianov

Russian MuseumIn pre-Petrine times, a woman's health was synonymous with being well-endowed. The wives of the aristocratic boyars were definitely ‘body-positive’ which was straightforwardly noted by foreigners: "They consider stoutness to be part of a woman's beauty. [...] Small legs and slender stance are considered ugly. [...] Skinny women are considered unhealthy," wrote the court physician Samuel Collins with astonishment.

At the same time, foreign travelers noted that Russian women were very beautiful: "Women of medium height, beautifully built, gentle face and body," this is how German geographer Adam Olearius wrote of Russian women in the 1630s. "Women in Muscovy have a slender stature and a beautiful face," wrote Jacob Reutenfels, a Baltic-born 17th century diplomat.

Russian Girl, 1889, by Karl Gottlieb Wenig

Russian MuseumThis attitude to female beauty in Russia was common to all classes. The life of a peasant woman in the village was filled with hard physical labor, which required great strength. The ideal of beauty was considered to be "full-bodiedness", that is, the ability to give birth to children and continue the family. And if among the nobility this ideal of beauty in the 18th and 19th centuries changed to more "European" tastes, among the common people it remained relevant much longer. "The standard of a girl's beauty is a smooth gait, modest look, tall stature, thick hair, fullness, roundness and blush," wrote Prince Tenishev in the early 20th century about the peasant women of Vladimir Province.

Russian girls themselves wished to be burly, as evidenced by the texts of many magic incantations Russian girls used for luck and good health. "I am taller than all grasses, more mature than azure flowers, whiter and brighter than all, my shoulders are imposing, breasts are big, face is round, cheeks are crimson," one of such incantations reads.

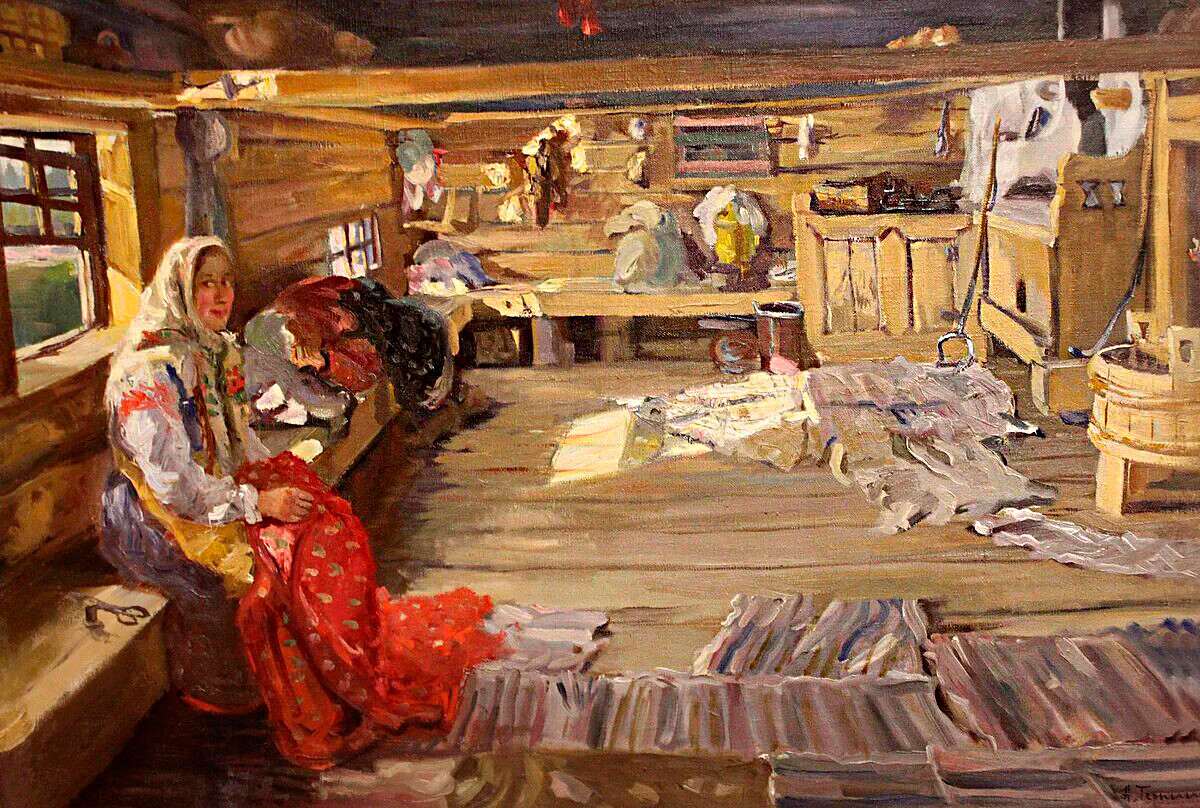

'A home in Vologda region,' 1925, by Nikolai Terpsikhorov.

Public domainThe Czech Jesuit Jiří David (1647-1713) who lived in Moscow in the 1680s, wrote that Russian women "walk smoothly in high clogs, because of which they cannot run or walk fast". Among the qualities of a noble woman, smooth manners and solemn gait were very much appreciated. Noble girls were taught to walk this way from childhood. At the same time, the sources do not mention that Russians valued idleness in women. On the contrary, sources on the history of merchants, for example, show that women often managed the finances and production themselves, including in pre-Petrine times. In village communities, elderly women were often heads of families, full participants in the village assembly.

READ MORE: How did single women survive in Tsarist Russia?

As Natalia Pushkareva, a historian of Russian women, writes, "the ideal of a wife was oriented towards a woman who was not professionally employed, but worked hard at home, ‘nourished the children and servants’, ‘made life seem as honey’ and ‘brought a lot of profit home’”.

Modesty and religiosity were valued as indispensable qualities of a good woman. As Pushkareva writes, "the term 'good wife' meant that a wife was 'submissive, humble, quiet." Both noblewomen and merchant wives in the imperial era tried to be faithful to this ideal: young noblewomen were brought up to be modest, graceful and easy of manners, while merchant daughters and wives were traditionally especially religious.

At the Dressing Table, 1909, by Zinaida Serebryakova

Tretyakov GalleryRussian women have always been very careful to care for their face and body – only the means differed between the rich and the poor. Every family, even the poorest, had a bathhouse that all family members visited once or twice a week. It was also possible to just wash in the bathhouse without lighting the stove inside and making a full Russian bath. Ash infused in the water – lye – was used for washing clothes and washing the body.

Effective folk remedies were used to tone and whiten the face and body: milk whey, cucumber brine, and herbal concoctions. One of the best folk remedies for natural blush, according to Empress Catherine II, was rubbing ice on one’s face. As her cabinet-secretary Adrian Gribovsky wrote, she ordered ice to have ice rubbed on her face every day. Irishwoman Martha Wilmot, who visited Russia in Catherine's time, wrote: "Every morning they bring me a plate of ice as thick as glass, and I, like a real Russian, rub my cheeks, from which, as I am assured, will be a good complexion.”

Obviously, richer women had access to European cosmetics even before Russia started producing its own cosmetic powders and creams in the second half of the 18th century. However, pre-Petrine women used cosmetics that were harmful for their health, and we have a separate article on this.

Girl with braids. Portrait of A.A. Dobrinskaya, 1910, Vasily Surikov

V.I. Surikov Art Museum, KrasnoyarskIn Old Russia, a wooden or bone comb for a girl was as valuable as a beard comb for a man. These combs were decorated with solar symbols, and they tried to grow their hair as long as possible, combed it for a long time every day and, of course, braided it.

Hair was one of the main female symbols, and it was made in one braid for girls, while for married women it was made in two braids. If a spouse died unexpectedly, these braids were cut off as a sign of mourning. The rite of making two braids by friends to their friend-bride was one of the ancient rites of female initiation.

READ MORE: What braids mean for Russian women?

Hair was cared for, washed with sour milk, boiled kvass, rinsed with nettle or chamomile decoction. It is important that the hair of noble women was not visible from under headdresses at all. Only the husband had the right to enjoy the beauty of his wife's hair and even comb it.

Moscow Girl of the 17th century, 1903, Andrei Ryabushkin

Russian MuseumAncient Russia hardly knew powder, lipstick, face whitewash and other cosmetics.They became popular among Russian women in the 15th and 16th centuries, already after Russian fashion was influenced by the fashion of Horde princesses and Middle Eastern beauties.

"It is the husband's duty to give his wife paint, for the Russian women have the custom of dyeing themselves; it is so common among them that it is by no means considered disgraceful," wrote Englishman Anthony Jenkinson in the 16th century. "They smear their faces so that one can see the paint plastered on their faces almost at a shot's distance; it is best to compare them with the wives of millers, for they look as if sacks of flour had been poked near their faces; they paint their eyebrows black," he wrote.

We have separate materials on why Russian women were forced to wear so much cosmetics, and how this fashion came to an end. Nevertheless, both in the 19th century and in Russia today, beauties were and are distinguished by their ability to use makeup.

Even the English poet George Turberville, who visited Moscow in the 16th century, noted: “But such as skilfull are and cunning dames indeed, by daily practice do it well, yes sure they do exceed: they lay their colors so, as he, that is full wise, may easily be deceived therein, if he does trust his eyes.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox