In 1689, the French diplomat Foy de la Neuville recorded that wife of Andrei Artamonovich Matveev, Anna (maiden name Anichkova), who was living in Russia, was "the only woman in this country who does not use whitewash and never blushes, so she is quite good looking".

Andrei Matveev was the son of the boyar Artamon Matveev (1625-1682), head of the government under tsar Alexei Mikhailovich and "the first Russian European". Matveev's house was furnished with foreign furniture, European paintings, and his wife was a Scottish woman, Evdokia Hamilton. A descendant of such a family could allow his wife to behave in a "European way".

While other noble Russian women continued to grease their eyebrows and whitewash their faces, Anichkova shone with natural beauty.

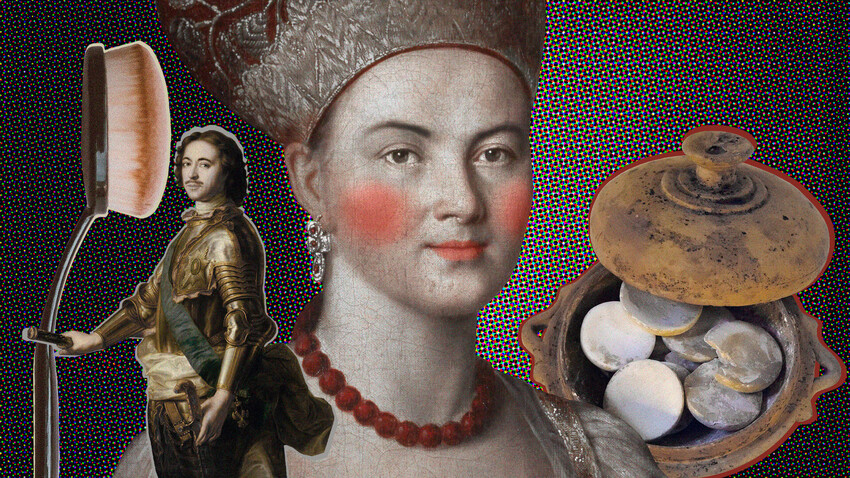

Nataliya Naryshkina, mother of Peter the Great

Hermitage MuseumNatalia Naryshkina, the mother of Peter the Great, had been taught manners in the Matveevs' Moscow estate, under Lady Hamilton’s supervision. When she became the tsarina in 1676, Natalia started doing things that were earlier unthinkable for a Russian noblewoman and for any woman – she watched theatrical performances, danced, and appeared in an open-topped carriage.

Natalia Naryshkina's son, Peter, did not like traditional Russia that was centered in Moscow, with its corpulent noble ladies who were clumsy and constrained in their long clothes. Peter preferred European coquettes in dresses with cleavage, and he introduced such dresses with his reforms. But how?

Portrait of Tsarevna Nataliya Alekseevna, Peter the Great's sister, by Ivan Nikitin, circa 1714-1715

Tretyakov GalleryOf course, already under Peter's father, Tsar Alexey, and under his older brother, Tsar Fyodor, European fashion became popular among Russia’s elite. However, that was primarily in men's clothing. Women's dress remained strictly traditional and very similar to men's – many layers, long-sleeved dress, fur coats with the fur turned to the inside.

Women were easily distinguished from men only by heavy cosmetics – lead whitewash was applied in layers and corrected by removing the layers so thick that a special scraper tool was necessary.

Peter began his reforms of Russian clothing almost immediately upon returning from his ‘Great Embassy’ to Europe, and which coincided with his effort to suppress the imperial guard, the streltsy, many of whom were executed on Red Square.

On August 29, 1698, Peter issued a decree "On wearing German dress, on shaving beards and mustaches". Why exactly did he do this during the executions of the streltsy? We can surmise that the great ruler wanted to emphasize that the old order was being destroyed, and any imitation was now forbidden.

Next decrees on wearing new types of clothing were issued in 1700, 1701 and 1705. In Moscow, mannequins decked in European dress were put up by the city walls so that everyone could understand how to dress. A substantial fine was introduced for wearing the "wrong" clothes in cities – 40 kopecks from pedestrians, 2 rubles from people on horseback (16 kilograms of meat cost 30-40 kopecks back then). The decree said separately about women: "the females of all ranks must wear German dress".

"An assembly under Peter the Great", by Stanislav Khlebovsky

Russian MuseumDespite initial protests and riots, German dress became fashionable. And from 1717, Peter the Great began to host assemblies, where by personal example – he and his wife Catherine – showed how to dress, dance and have fun. But how did all this affect women's cosmetics?

A still from "Marie-Antoinette," directed by Sofia Coppola, 2005

Sofia Coppola/American Zoetrope, 2005German women's dresses of the early 18th century implied open arms, open neckline and part of the back, and, of course, headdresses and hairstyles. Such an image was incompatible with Russian women's cosmetics of the 17th century – it would have been too expensive to whitewash all the open parts of the breast and arms. In addition, it is impossible to laugh and dance in thick makeup, and Moscow noblewomen had never done any of this in public before.

When dancing became a public entertainment, and the ability to dance became an indicator of one’s nobility, the very pace of movement of the Russian female changed. In Muscovite Russia, a beauty had to walk like a swan – floating, her legs hidden by a long-sleeved garment, while the upper parts of the body remained motionless.

In contrast, the 18th-century beauties, with their arms and backs exposed, were in constant motion, flirting, laughing and dancing. The hair, which Russian women had previously hid under their clothes since they considered it a part of their naked bodies, now became material for fashionable hairstyles according to the new fashion, and the base for wearing crazy wigs and headdresses.

Of course, Russian ladies at first lacked not only taste, but also skillful tailors. Foreign tailors and fashion designers only began to teach Russian seamstresses and dressmakers to make new styles in the 1710s – 1720s. That’s why even the leading people working in government in Europe looked out of fashion.

Princess Wilhelmine of Prussia was just 10 years old when she saw Peter and Catherine during their visit to Berlin in 1719. "The dress she wore was probably bought in a marketplace. It was an old-fashioned thing, all lined with silver and sequins. By her attire one could mistake her for a traveling entertainer," is how the young princess wrote about the Russian tsarina.

Portrait of a young Elizabeth Petrovna, daughter of Peter the Great and the Russian Empress from 1741 to 1761, by Ivan Nikitin, circa 1720

Russian MuseumIt took another 20-30 years before Russian fashionistas could compete with their European peers. By the middle of the 18th century, a woman’s natural complexion became fashionable.

For whiteness of the face, skin was washed with steamed milk, cucumber brine, and decoction of cornflower. As culturologist Oksana Mayakova comments – wolf's tallow, ointments that were based on egg white, and oils from flowering wheat were used to clean the skin.

Catherine the Great recalled that in her youth she suffered from acne and pimples on her face, but she was helped the imperial medic: "He took out of his pocket a small vial of talc oil and told me to put one drop into a cup of water and wash my face with it from time to time; for example, weekly. Indeed, the talc oil cleansed my skin and in ten days I could show my face."

Women of that era also used dried thistle powder, which was rubbed on the face for freshness. But the most famous Russian remedy for fresh face and skin, used by everyone from peasant women to tsarinas, was snow and ice rubbing. During long, cold winters the Russian peasant women regularly went to the bathhouse, and after taking in the steam, they dived into an ice-hole or a pile of snow – a simple procedure that helped keep the tonus of the skin.

But the nobility was not lagging behind. Adrian Gribovsky, the Cabinet Secretary of Catherine the Great, wrote that during her morning toilet, “the Empress rubbed her face with ice.” Irishwoman Martha Wilmot, who visited Russia in the beginning of the 19th century, wrote: "Every morning they bring me a plate of ice as thick as a glass, and I, like a real Russian, rub my cheeks, from which, as I am assured, will be a good complexion of the skin.”

At the same time, the use of rouge and powder were not neglected – it’s just that now they were made according to European recipes and not based on lead and mercury. In the time of Catherine the Great, Russia had four powder factories and five rouge factories; in addition, foreign cosmetics were widely on sale. A jar of rouge was expensive: 80 kopecks. This compares with the fact that with 10-12 kopecks the average Russian could eat a hearty meal in a tavern.

Portrait of Martha Wilmot, Irish writer and traveler

Public domainHowever, historian Marina Bogdanova points out that: “Being dyed and painted as their great-grandmothers was unthinkable for young ladies of the new era. Cosmetics became more diverse – blushes were already differentiated by shades, from scarlet to soft pink, and the fashionista could pick up the right tone, which she needed to go with the color of her ribbons or dress.”

By the end of the 18th century, popular books and magazines for fashionistas, at first mostly translated, became popular in Russia. They offered women recipes for self-made powders, creams, and lotions. Russian ladies began to use them often, and by the beginning of the 19th century, bright makeup was a thing of the past. The natural look, only slightly touched with powder, again became fashionable, and the best blush was considered natural.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox