“On September 8, 1941, we gathered in the yard and saw a red and crimson glow in the sky. This was an amazing sight, I still remember this sky. It seemed to us that it claimed the entire sky from Moscovsky railway station to the Admiralty. Later, we learned that it was the glow from a fire – the Germans had bombed the Badaev warehouses storing the food supply for the denizens of the city,” Leningrad resident Zinaida Fedyushina remembered, who lived through the entire siege when she was a schoolgirl.

From September 8, 1941, to January 27, 1944, – 872 days – Leningrad was surrounded by the enemy. The city, which Nazi German invaders planned to wipe off the face of the Earth, was cut off from the rest of the country. The only link was the ‘Road of Life’ over Lake Ladoga. By that route, food and essential goods were delivered, while the population of the city was slowly evacuated. In 1942, the ‘Cable of Life’ was laid on the bottom of the lake to supply the besieged city with electricity.

From Summer 1941 to the end of 1943, more than 1.7 million people were evacuated from Leningrad. Those who remained, in harsh conditions, ensured the uninterrupted operation of factories and municipal services, schools and hospitals, theaters and banks; they also protected the city from fires and epidemics.

Separate addresses on the map of modern St. Petersburg maintain their sacred importance: they became the symbols of life and death in the besieged city.

At the beginning of the siege, signs stating: ‘Citizens! During artillery shelling, this side of the street is the most dangerous’ began appearing on the city streets – about 1,500, in total. German troops were shelling the city from the south and south-west, so the warnings were put up on the northern and north-eastern sides of the streets. Crossing the road could save one’s life.

After World War II, these signs didn’t survive. However, some were restored in the 1960s-1970s. The most famous one is located at Nevsky Prospekt, 14, on the building of school №210, which didn’t stop operating during the siege. In 1973, the Museum of Young Participants of Leningrad’s Defense opened in it.

The Fontanka River embankment, 3

This is one of the three substations of Leningrad that ensured the operation of trams – the only means of transportation in the besieged city. Military regiments, shells, machinery, equipment, as well as the wounded were all transported on trams.

Over the course of the siege, trams were only not in operation in the Winter of 1941-1942. In November 1941, power outages began in Leningrad. On January 25, 1942, the city had minimal power generation: only one turbine with a 3MW load was working in the city. In March 1942, the ‘Red October’ power station was put into operation, with its boiler repurposed for burning peat. On March 21, 1942, cargo trains appeared on the streets again; and, from April 15 onwards, passenger ones joined them.

“The first tram coach went along the cleared Nevsky Prospekt. People forgot about their work and watched, like children watch a toy, as the coach rolled along the rails; suddenly, a 10,000-strong applause sounded. The Leningrad denizens welcomed the first resurrected coach with an ovation,” writer Nikolai Tikhonov remembered in his ‘Leningrad Tales’.

The traction substation №11, located in the center of the city – along with the tram – became one of the symbols of besieged Leningrad. It managed to operate until 2014.

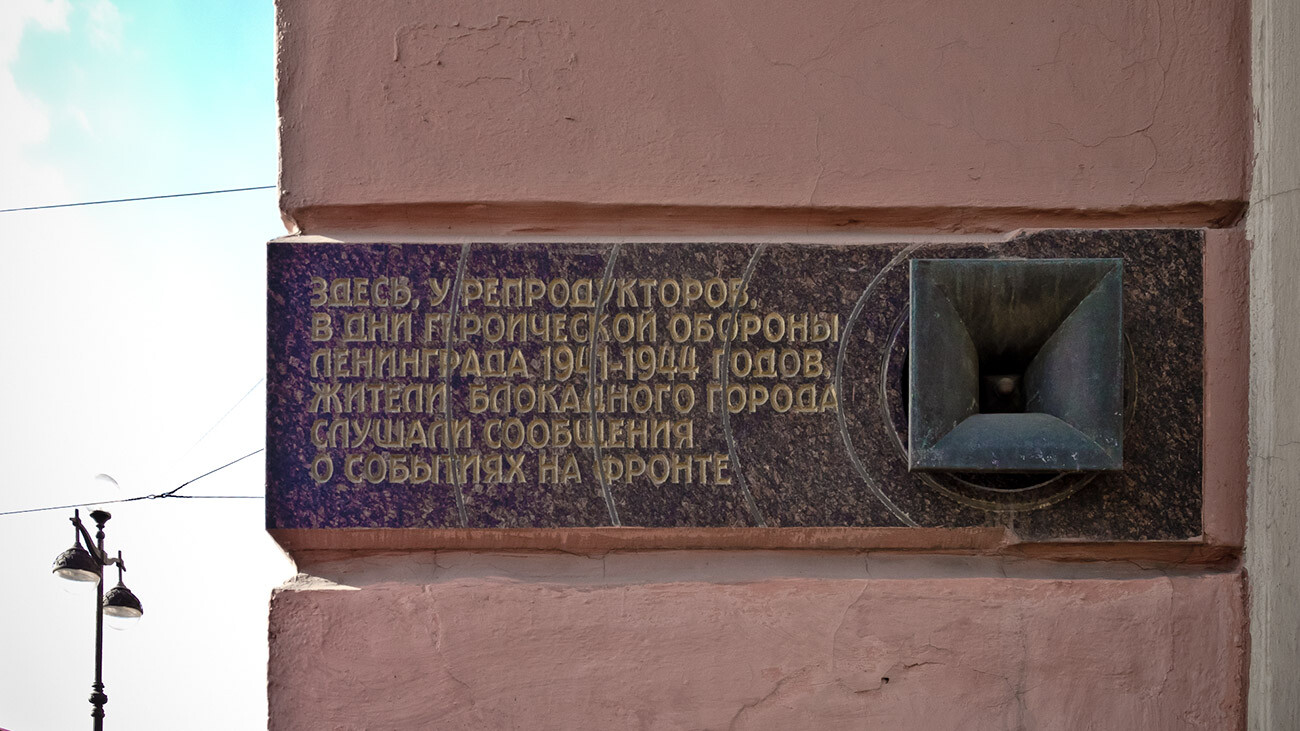

Radio maintained the link between Leningrad and the rest of the country, replacing post. It transmitted the messages from the Soviet Information Bureau and air raid warnings. Speakers read not only the news and instructions, but also the works of Russian classics and also broadcast symphonies. A metronome, meanwhile, sounded during breaks. After the announcement of an air raid, it beat faster, alerting the citizens about danger.

The broadcast was done through street loudspeakers. Homes had no radio receivers: by the decision of the government, it was ordered to give them to the state for storage. In any case, apartments often had no electricity. On-air broadcasting was impossible, due to the possible interception of waves by the enemy.

When radio was silent during power outages, the Leningrad denizens, “who waited for the voice of the radio like for bread, with their last slivers of strength went from across the city to the radio committee to learn what had happened. <...> People asked: no matter what, whatever strife there may be, let there be no water and bread, let there be inhuman conditions, we just need the radio to work! Without it, life stops. This should be prevented at all costs!” Yuri Alyansky remembered in the book ‘Theater In The Shelling Area’.

The monument to the siege loudspeaker can be found on the corner of house at Nevsky Prospekt, 54, 200 meters away from the ‘House of Radio’.

The Fontanka River embankment, 21

During the siege, especially during the first Winter of 1941-1942, there were not only power outages, but also water supply shortages.

“During the first days of the war, a bomb hit the water supply pipes near a banya (bathhouse). There was a giant crater, with a thin trickle of water pouring on its bottom from a pipe. Water was cut off from the houses and a colossal waiting line formed near the crater to get some water. It was incredibly hard getting to the bottom of it, especially when the cold came. No one tried to fix the water pipes. There were bombings every day, really hard. And waiting lines of people were shot at from planes,” Leningrad citizen Emma Kazakova remembered.

So, to get water, people went to the embankments, where they scooped dirty river water from ice holes.

”A giant waiting line on the river’s ice; pots, buckets and tanks transported on sleighs. The ice hole, from which people got water, was guarded by two soldiers that maintained order. Suddenly, a woman, who was scooping water, fell face forward into the hole. The soldiers pulled her out by her legs and dragged her to the side. She was dead. My turn comes. I fill up a tank and bring the precious water home, where my mom was waiting for me anxiously and impatiently,” Zinovy Khanin wrote in his diary.

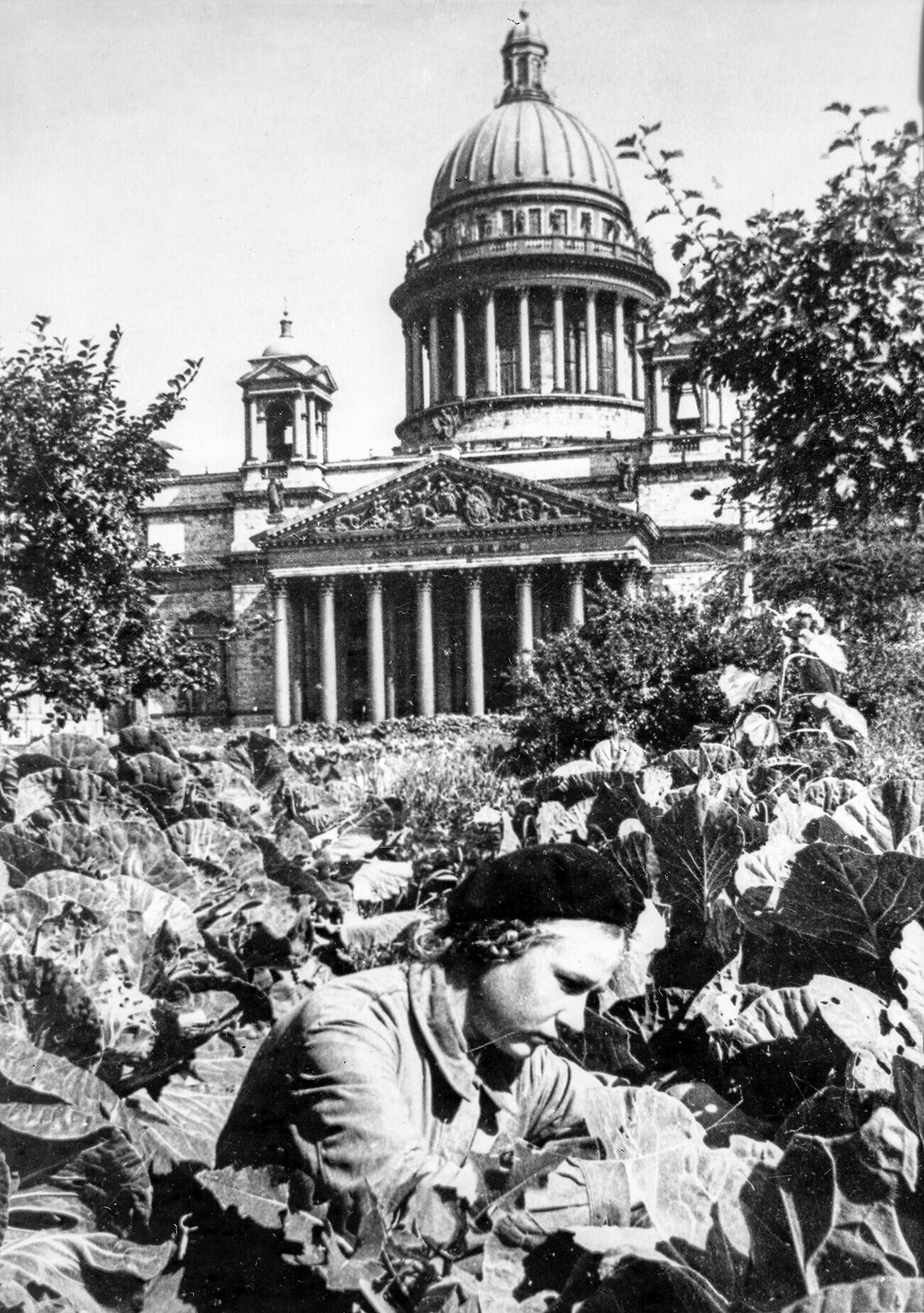

In Spring 1942, after a harsh winter, the Leningrad denizens began organizing collective kitchen gardens on vacant lots and in gardens, on stadiums, in yards and parks. One of the prettiest squares of the city – Saint Isaac's Square – also turned into a seedbed: people were growing cabbages.

The basements of St. Isaac’s Cathedral, the domes of which were covered by masking gray oil paint back in July 1941, harbored museum treasures evacuated from the suburbs – from the museum palaces of Pushkin, Pavlovsk, Petergof, Gatchina and Oranienbaum. All these towns, except for the last one, were occupied by the Nazis.

The Institute of Plant Industry is also located on this square. Over the course of the siege, its employees managed to protect the entire seed fund. The employees, starving to death, didn’t abandon their post: they protected dozens of tons of grain and tons of potatoes from cold, dampness, rats, German shelling and thieves. Thanks to the preserved collections, the country managed to rapidly restore its agriculture after the war.

This station on the blue Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) Metro line was opened in 1961. The entrance to it is located near Moskovsky Victory Park, from which the station got its name. Until 1960, the Brick-and-pumice Factory №1 stood on this place instead of the pavilion. Before that, in 1942-1943, it was a re-purposed crematorium.

According to witnesses, it had a working capacity of about 800 bodies per shift. The cremation was done in three shifts. Ashes were dumped into the factory quarries, where, later, a park was created. According to archive data, the remains of 130,000 Leningrad citizens rest there. For a long time, the documents about the factory’s “special task” were classified.

In 1999, a reusable mine-cart hearse, one of those sent to the crematorium ovens, was lifted from the bottom of the park pond. In 2001, it was turned into a monument.

The crematorium operated in the south of Leningrad, while, in the north of the city, the dead were accommodated by the Piskaryovskoye Cemetery. Over the course of the siege, 420,000 citizens and 70,000 soldiers were buried in 186 mass graves and 6,000 individual graves.

“The entire ditch along the cemetery was filled with corpses. There was no circling this creepy place – there was no footpath or another road around. Cars came and, like logs, hauled frozen corpses over. I tried not to look at the deceased, but I still remembered that there were children bodies. I think, only a few people exist on Earth, who saw as many corpses in their lives as I did, a nine-year-old boy; there were, probably, tens of thousands,” Anatoly Nikonov, who lived nearby, described Piskaryovskoye Cemetery in November 1941.

On May 9, 1960, a memorial to the Leningrad denizens who died during the siege was opened in the cemetery. An eternal flame burns at the entrance, lit from the memorial on the ‘Field of Mars’. From it, a 300-meter alley begins, leading to a six-meter-tall bronze ‘Mother Homeland’ sculpture. Behind it is a steel wall with six reliefs, depicting the episodes from the life of the Leningrad denizens during the siege. Four times a year, people hold mourning ceremonies there.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox