Nikita Khrushchev.

Valentin Sobolev/TASS

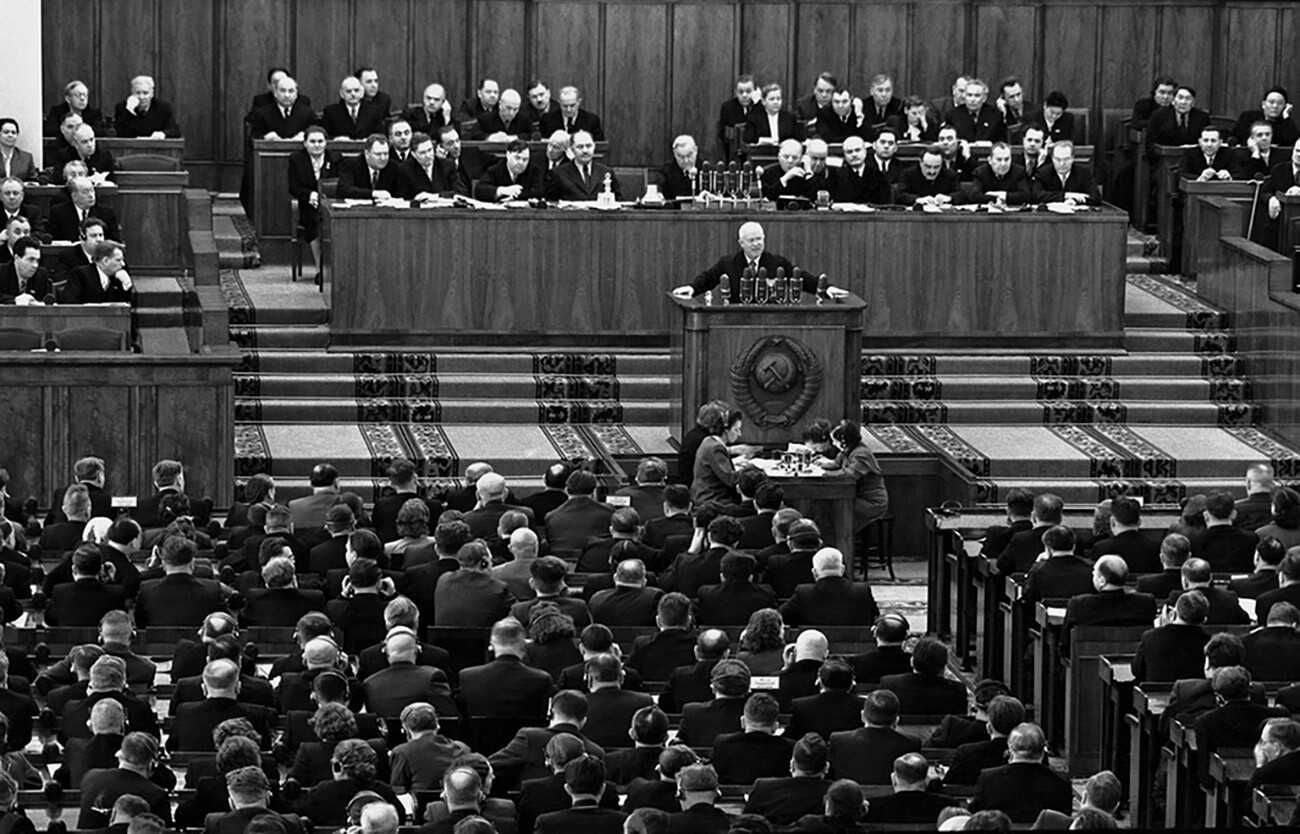

Nikita Khrushchev speaks at the 20th Party Congress.

Alexander Ustinov/The union of Photographers of Russia/russiainphoto.ruThe ‘Thaw’ was a period in the history of the Soviet Union characterized by the partial liberalization of political and public life, a systemic “de-Stalinization”, the rehabilitation of the victims of Stalin's regime, a transition from totalitarianism to soft dictatorship, a relaxation of censorship and a certain degree of creative freedom.

The beginning of the ‘Thaw’ can be traced to February 25, 1956, when Nikita Khrushchev delivered his ‘On the Cult of Personality and its Consequences’ report to the 20th Congress of the CPSU (Communist Party of the Soviet Union). In it, he forcefully denounced Stalin's personality cult and many aspects of the former leader’s policies.

In doing so, Khrushchev intended to revamp the political system and restore people's trust in the Party. Despite the freedoms that were conceded, the state retained control over all the processes occurring in Soviet society.

The ‘Thaw’ was characterized by extreme contradictions. Openness to the world and a desire to normalize relations with the West went hand in hand with the suppression of the Hungarian Uprising against Soviet authority in 1956, while talk of cultural and intellectual liberalization coincided with the shooting of protesting workers in Novocherkassk in 1962 and a large-scale campaign against religion.

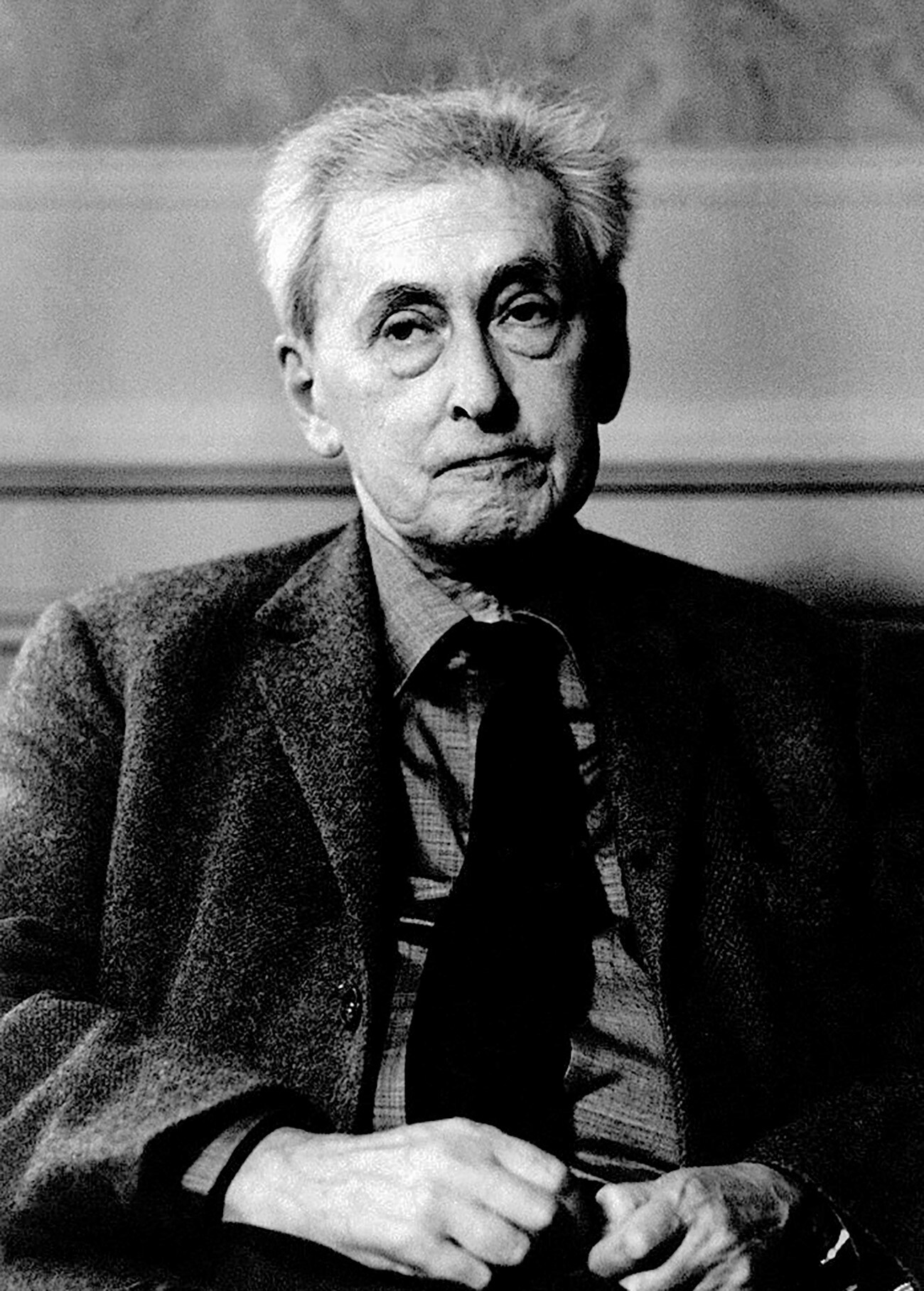

Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg.

Public DomainThe political term ‘The Thaw’ was derived from Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg's eponymous novel about the life of the working and creative intelligentsia in a provincial town. The author published it in 1954, two years before Khrushchev's famous speech at the 20th Congress.

Ehrenburg began to work on the story soon after the death of the ‘Father of Nations’. In it, he cautiously expressed the idea of imminent changes in the USSR. "I wanted to show how momentous historical events affect the lives of people in a small town and to convey my perception of a thawing, my hopes…" he later wrote in his memoirs.

Khrushchev didn't like it when his time in office began to be referred to as the ‘Thaw’. For him, the word was associated with muddy snow.

But, after leaving office, at the end of his life, Nikita Sergeyevich changed his mind and agreed that the name was basically an apt one.

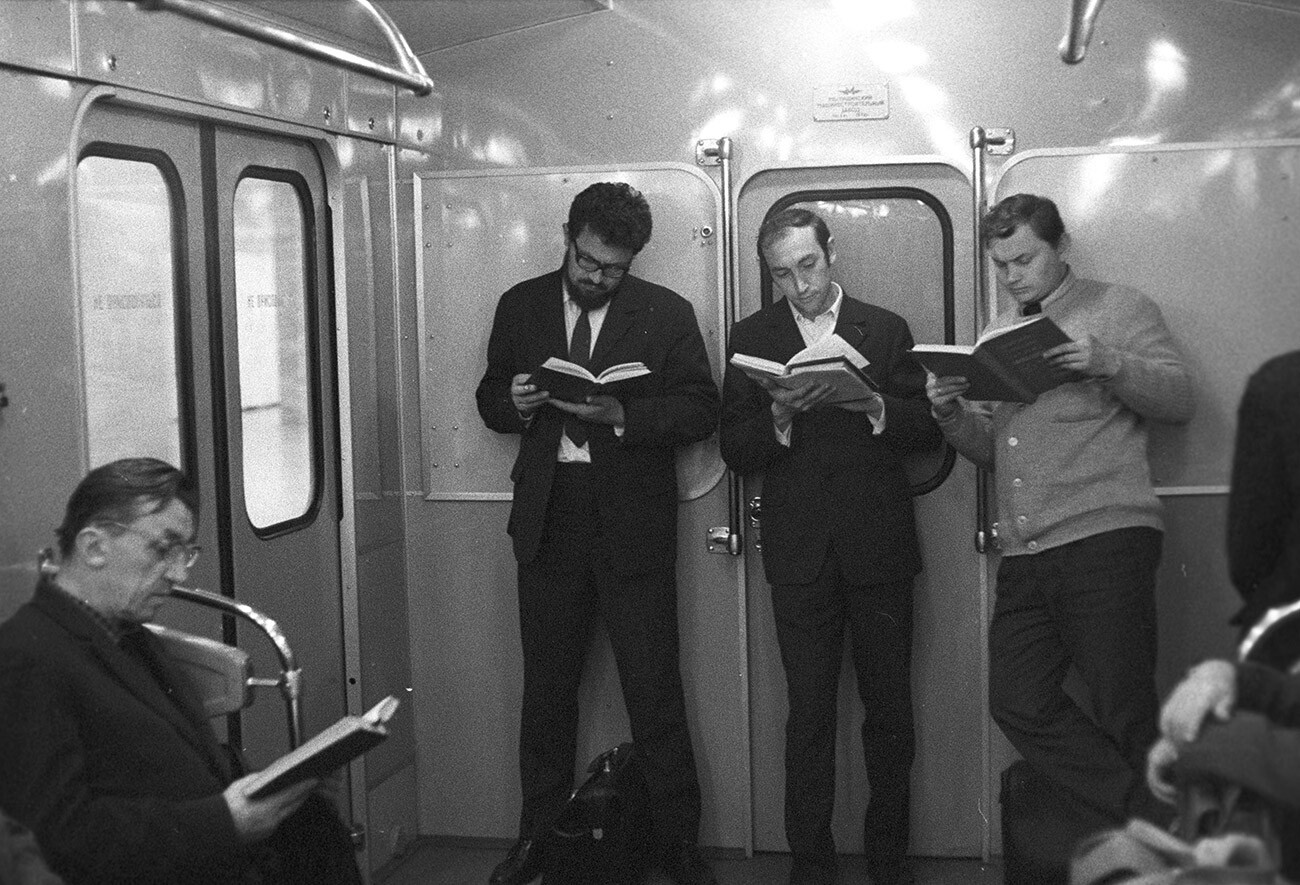

Moscow metro passengers.

Igor Gavriilov/SputnikThe processes of “de-Stalinization” and partial liberalization initiated by the authorities had an impact on all aspects of Soviet society.

In the literary sphere, there was a loosening of censorship. People were given the opportunity to read the previously banned poetry of Osip Mandelstam, Konstantin Balmont and Marina Tsvetaeva, as well as Mikhail Bulgakov's novel 'The Master and Margarita'. Alexander Solzhenitsyn's story ‘One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich' about the daily life of an inmate of a correctional labor camp, meanwhile, came out in 1962.

New, up-and-coming authors were now being published in the liberal journal 'Novy Mir' (‘New World’), with poetry enjoying particular popularity. Poets such as Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky literally filled whole stadiums with audiences wanting to discover their works.

During the ‘Thaw’, large numbers of people in the Soviet Union were finally introduced to the novels of foreign writers (such as Erich Maria Remarque and Ernest Hemingway), as well as the work of foreign musicians. For instance, the Benny Goodman jazz band from the U.S. toured the country with great success in 1962.

In cinema, great leaders and ardent revolutionaries were replaced by ordinary people with their problems and aspirations. For instance, in Georgy Daneliya's movie 'Walking the Streets of Moscow' (1963), the protagonists don't perform any heroic deeds, but merely stroll around the capital.

In architecture, the lavish Stalinist Empire style with its bas-reliefs and columns gave way to the construction of standardized five-story apartment blocks. As Khrushchev announced to disappointed architects: "People need apartments. They aren't interested in admiring silhouettes; what they need is houses to live in!"

Soviet poets Bulat Okudzhava, Andrei Voznesensky, Robert Rozhdestvensky and Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

Dmitry Baltermants/МАММ/MDF/russiainphoto.ruThese fundamental changes in society led to the emergence of a new generation of Soviet intellectuals known as the ‘Sixtiers’. They believed in humanism, creative freedom, the freedom to express themselves, as well as the human right to a private life.

There were ‘Sixtiers’ among artists, actors, poets, writers, musicians and so on. They held gatherings in private apartments and could spend the whole night discussing culture, the role of the state or simply the meaning of life.

Although some of them became opponents of the Soviet authorities and joined the dissident movement, the bulk of the ‘Sixtiers’ believed in the ideals of Communism. They proposed achieving communism through moderate democratic reforms.

The ‘Prague Spring’.

Yuri Abramochkin/SputnikAuthorities never gave the ‘Thaw’ a chance to develop fully and always maintained unambiguous control over social processes. An anti-Soviet joke would be enough to get someone hauled before the courts.

"In deciding to usher in the 'Thaw' and making it a deliberate choice," Khrushchev asserted, "the USSR leadership, which that includes me personally, were simultaneously anxious that it should not lead to a flood that could engulf us and with which it would be difficult for us to cope… We were afraid of losing our previous opportunities for running the country in a way that contained the growth of sentiments that were unwelcome from the leadership's point of view."

Leonid Brezhnev's assumption of power in 1964 saw the beginning of a vigorous clampdown on dissent and stricter censorship. Just a year later, legal proceedings were started against writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel on charges of anti-Soviet propaganda.

After being formed in 1965, the organization of young poets known as ‘SMOG’ (an acronym made up of the words ‘Smelost’, ‘Mysl’, ‘Obraz’ and ‘Glubina’ - ‘Courage’, ‘Thought’, ‘Image’ and ‘Depth’) only managed to exist for about a year. After it refused to submit to the jurisdiction of state officialdom, it was broken up and its leader, Leonid Gubanov, was sent for forced treatment to a psychiatric hospital.

The final ending of the ‘Thaw’ is associated with the snuffing out of the period of liberalization in Czechoslovakia in 1968 known as the ‘Prague Spring’. Many of the ‘Sixtiers’ came out in support of the Czechoslovaks, something that led to them being subjected to repressions and driven to join the dissident movement. The so-called "period of stagnation" had begun in the country.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox