Traveling across Russia and visiting different cities that sometimes are separated by thousands of kilometers, even an unobservant tourist can spot identical five-story blocks with an unremarkable architectural style. Most of them were erected when the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was in office (1953 to 1964), in whose dubious honor they were dubbed “khrushchyovkas”.

Some people in Russia are quite dismissive towards these buildings nowadays: they say the apartments are cramped, the ceilings low, there’s no elevator, and the blocks themselves are physically obsolete. However, these mundane apartment blocks literally revolutionized the Soviet man’s consciousness. In khrushchyovkas, people gained the right to their own private space and a little speck of freedom.

A new apartment building construction

The Southern Urals historical museumDuring the period of mass construction of khrushchyovkas, the residential housing problem in the USSR was one of the most acute social problems: the rapid industrialization of the Stalinish era had led to an ever-increasing number of workers flowing from the countryside to the cities. The task of resettling the inhabitants of temporary barrack dorms had been somewhat successfully solved under Stalin. While these cramped and squalid buildings were no longer common, one could still stumble upon an occasional barrack even in the capital.

Construction of one of seven Stalinist skyscrapers, Kudrinskaya Square Building, 1952

Ivan Shagin/SputnikThe bulk of the population had moved into “stalinkas” – blocks of apartments built from 1933 to 1961. Stalinkas were built not only for the nomenklatura and the intelligentsia - the elite of Soviet society - but also for regular citizens. But it was nearly impossible for a regular person to get a private apartment in a stalinka, which were five to 11 stories high) and usually filled with communal apartments; several families occupied a single apartment, each inhabiting one or more rooms.

Construction of a new residential block in Moscow

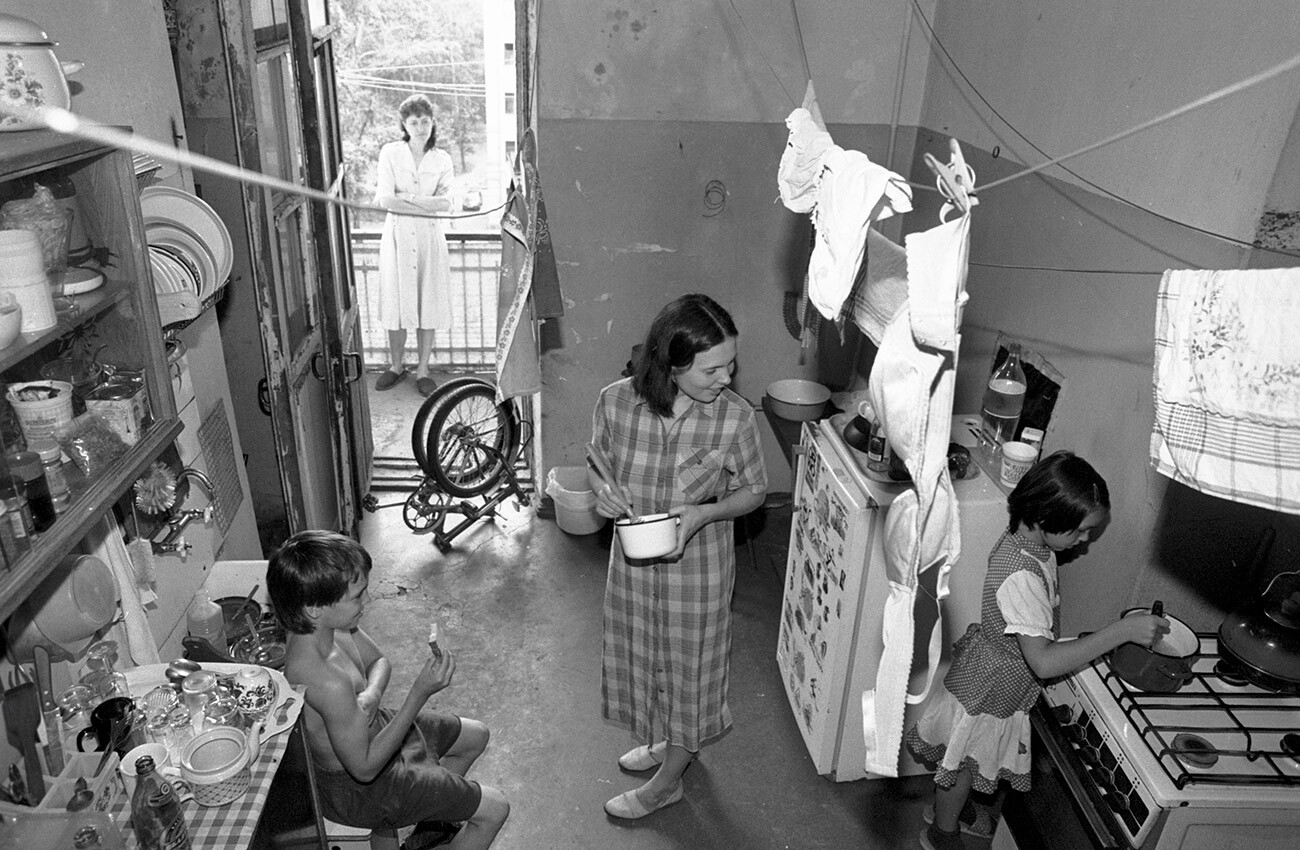

Yury Skuratov/SputnikThe kitchen, the bathroom, and the main hall were shared, which created further problems for residents – the people who lived there remember long lines to the bathroom, strictly limited shower time, noisy or, to the contrary, excessively strict neighbors, the smell of cooking that wafted from the kitchen, and the complete absence of personal space.

Kitchen in a communal apartment

Oleg Lastochkin/SputnikAt times, disputes turned into brawls or sneaky attempts to evict one’s neighbors – through denunciations, complaints, and machinations that could lead to arrest. In this case, the room, now free of its tenant, was handed to their neighbor.

In 1953, after Stalin’s death, the authorities decided to finally deal with the housing shortage within the next 20 years. To implement such an ambitious plan, projects of cheap-to-construct blocks were designed – khrushchyovkas.

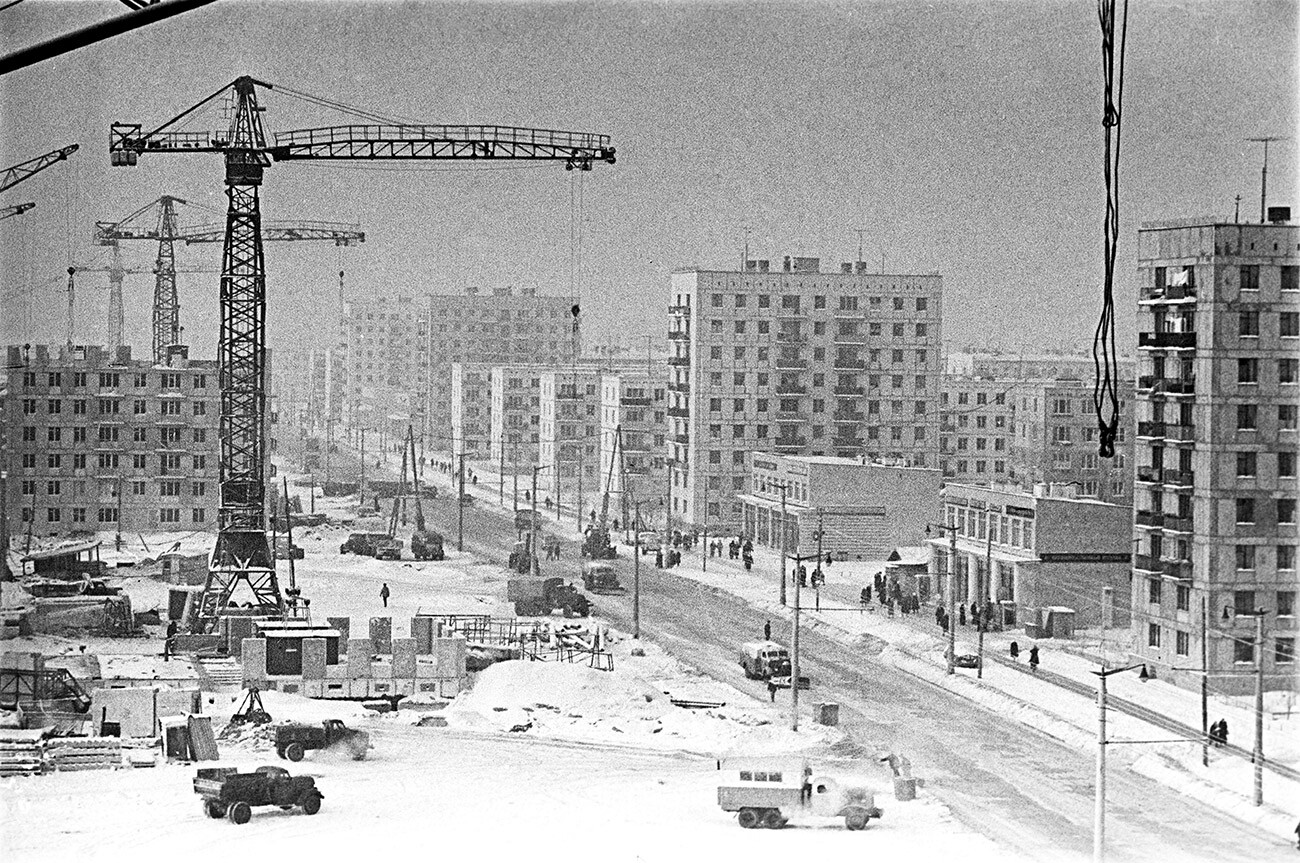

A new residential district in Moscow

Lev Polikashin/SputnikErgonomics were the main concern; the five-square-meter kitchen was designed based on the set of movements required for the preparation of a basic set of dishes, the standard living space per person amounted to 12 square meters, the apartment had a combined bathroom – no frills.

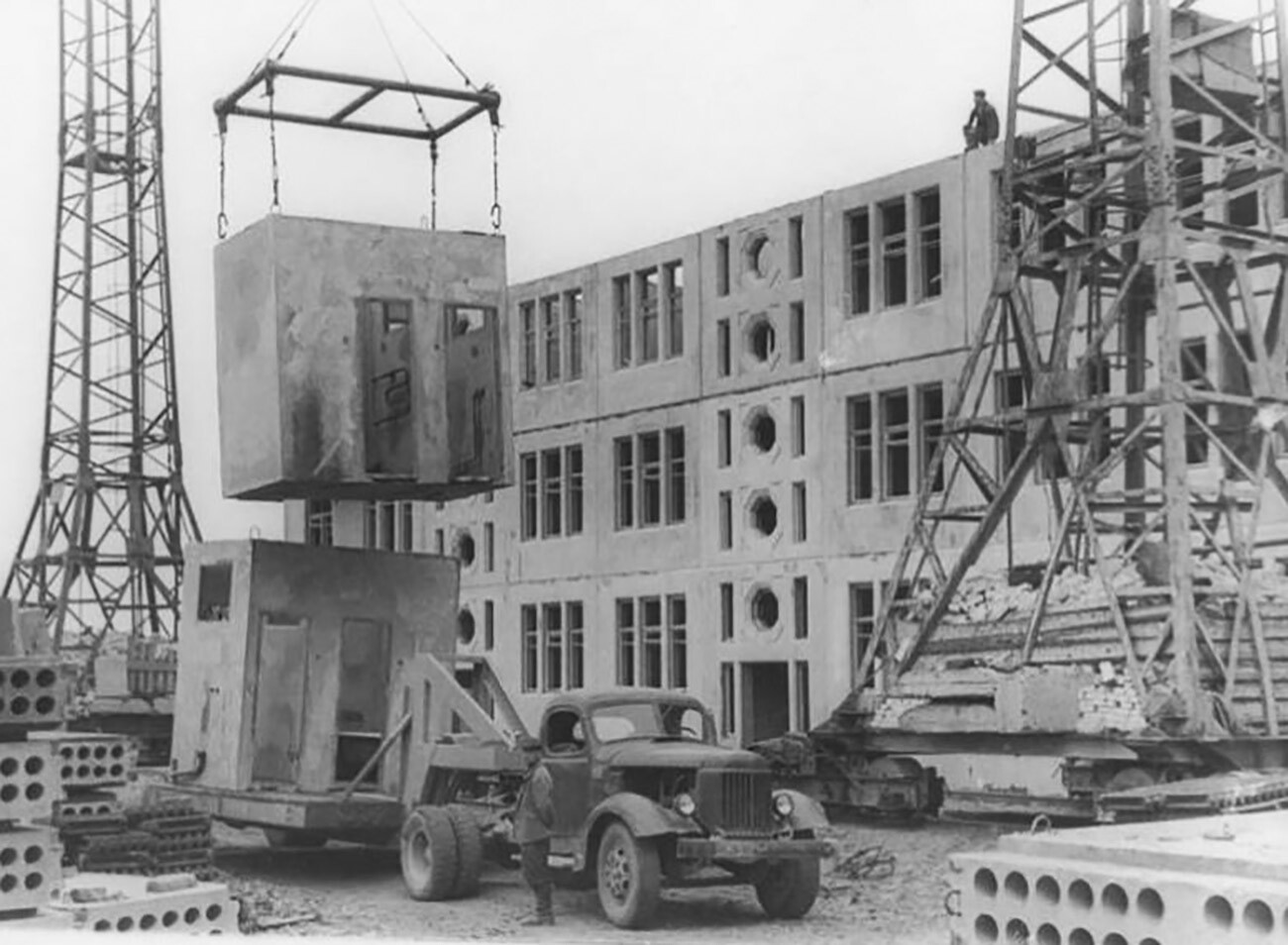

Unloading of sanitary facilities on the construction site of large-panel houses

G.Yefimovsky/Cherepovets Museum UnionDepending on the number of family members, one-, two- and three-room apartments (consisting of a kitchen, a bathroom, and one, two, or three living rooms respectively) were assigned, with the total apartment size reaching a maximum of 58 square meters. Perhaps, after stalinkas, such apartments didn’t seem excessively large, but it still was one’s own private space.

“My first thought was: it’s so spacious! Two large rooms, our own kitchen… Now it’s obvious that it was small, but back then it seemed like a mansion! And there was always hot water,” Marina Tsygankova remembers, who in those times moved into a khrushchyovka with her family.

Transportation of a concrete block

Boris Kravets/SputnikKhrushchyovkas were a major breakthrough in the improvement of the country’s housing stock; one block took 12 days on average to build, which allowed the authorities to resettle millions of people in individual housing in a short time. Such a rapid pace of construction didn’t always mean low construction quality – both brick and concrete block khrushchyovkas are still in a livable condition today and can even give some of the new buildings a run for their money when it comes to longevity. However, panel khrushchyovkas began to crumble after just 30 years.

A panel khrushchyovka construction

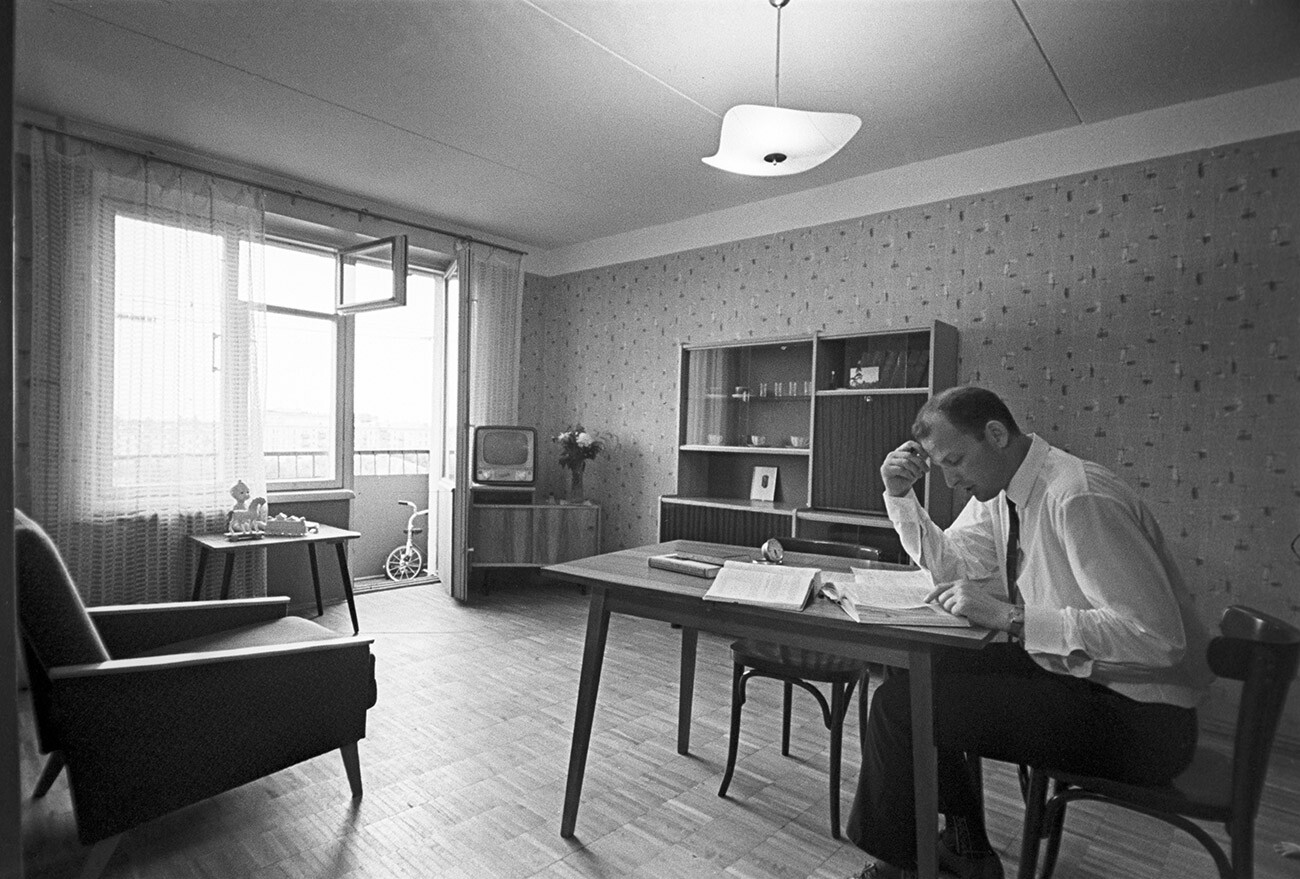

Viktor Yershov/MAMM/MDF/SputnikThe apartments themselves, through the eyes of a person from the 1960s, were quite comfortable: they weren’t shared, they had a storage closet, and there were only five stories in the entire building.

It’s also worth noting that, in the USSR, these apartments were given out to people free of charge, the number of rooms depended on the number of family members. However, one needed to wait for their turn to receive one from the state, and that could take years.

“My parents and I lived in a communal apartment for three families. When we were given a two-room apartment in a brick khrushchyovka from my dad’s factory, we were on cloud nine. I finally had my own, although very small, room. My mom was happy to have our own bathroom and kitchen. Our life began to be quite different,” says Vladimir Orlov.

Kitchen furniture set at the "Art into Life" exhibition in Moscow, 1961

Yury Abramochkin/SputnikDesign solutions that emerged in order to furnish khrushchyovkas still inspire furniture brands. The modest apartment size forced Soviet designers to turn to minimalism; hence, a chair-bed, a gateleg table, and the “Helga” cabinet, which became symbols of the era, were born. What earlier was considered “grandma furniture” and “old relics” are now sought after in flea markets and restored to revive the 1960s aesthetic.

A khrushchyovka apartment typical interior

Vladimir Akimov/SputnikOnce, moving into khrushchyovkas was seen as a simple quality of life improvement, as an opportunity to break free from the discomfort of communal living. Looking back, however, it’s clear that the happy owners of these new apartments also broke free from the communal mindset when they moved out.

A tiny but private kitchen

Boris Kavashkin/SputnikThe previous way of life disrupted one’s privacy, and Khrushchev succeeded in changing that: new comfortable housing had awoken an individualist in the Soviet man. They could do whatever they want, decorate the apartment however they pleased, and not ask for anyone’s permission.

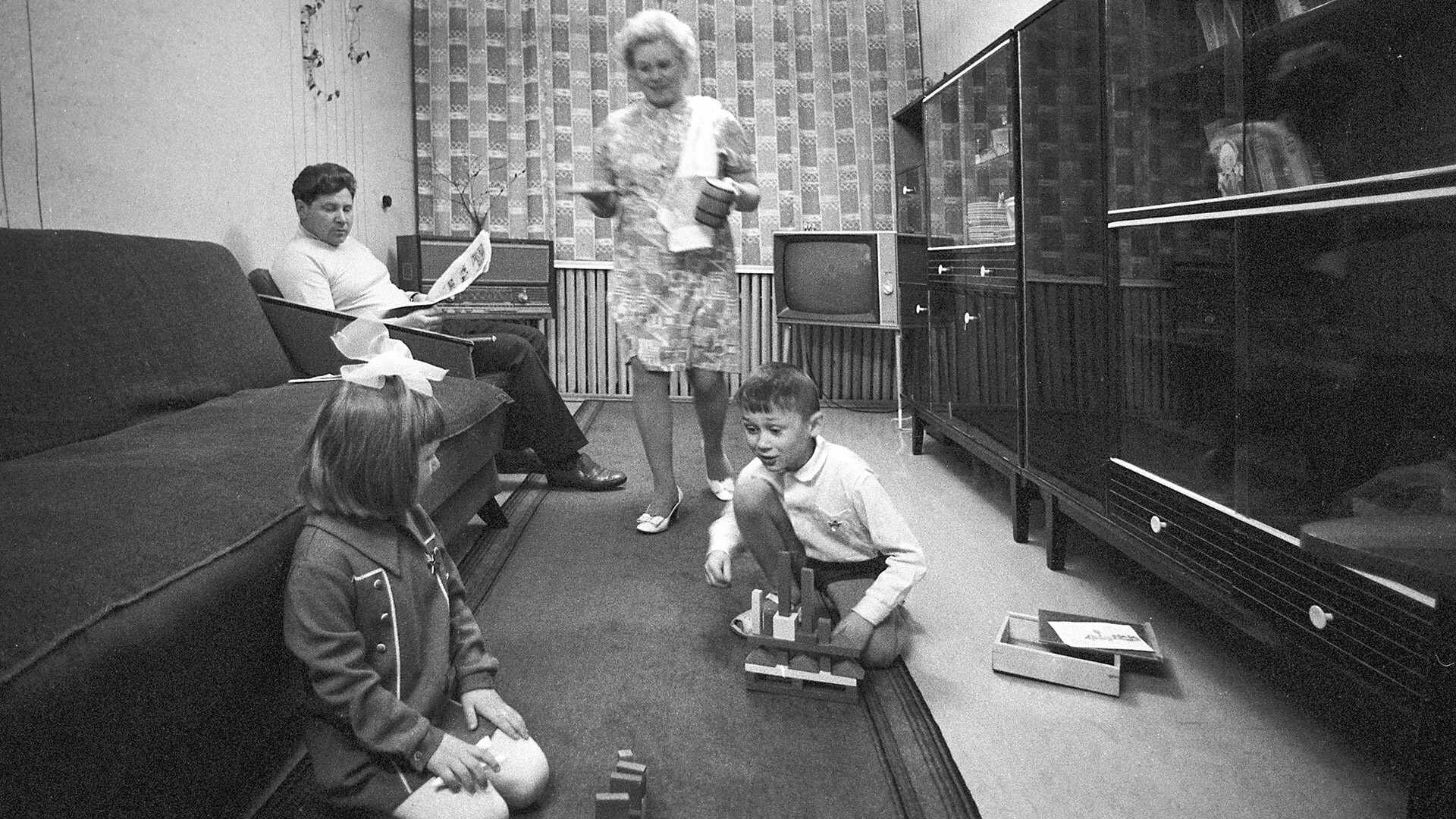

A family in their own new apartment

Boris Ushmaikin/SputnikAlong with individual housing, a new phenomenon emerged called a “home concert” – a musical performance presented in someone’s apartment, just for those in the know, since many informal groups and performers were banned from performing in public. In the 1960s, many future stars performed at such home concerts – for instance, Vladimir Vysotsky. As such, individual housing, given to the people by the state, created a platform for counterculture.

Small apartments still could be filled with many guests, especially for a home concert

S. Kryachko/SputnikCuriously, the period of khrushchyovka construction partially coincided with the period that received the name Khrushchev’s Thaw – censorship was relaxed, the GULAG ended for the most part, and Moscow raised the Iron Curtain slightly. The country underwent great change, and with it, the mindset of the people.

One still can stumble upon khrushchyovkas in all countries of the post-Soviet space, as well as in Germany and in Cuba. Some should have already been demolished, but many others are beloved by their tenants that don’t want to move to new apartments, despite offers by the authorities.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox