"There were sledges, harnessed to dashing troikas [three horses - ed.], decorated with ribbons and bells with crimson jingle, simple city sledges; ugly, ridiculously heavy carriages; and hunting sledges, pulled by strong, barely restrained trotters. Visiting wives of local aristocrats radiated in the carriages; young gentlemen flaunted their hunting sledges and trotters.

At times, a troika left the row and rushed through the middle of the street, raising clouds of snow dust, after it in pursuit flew a few hunting sledges, overtaking each other, laughter and squealing was heard, young women's faces bruised with frost fussily turned back and at the same time impatiently nagging their coachmen to go faster.” This is how writer Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin describes holiday sledge riding in one of the Russian provinces.

A Russian miniature from the 17th century shows people riding in sledges in summer

Public domainThe sledge is not a Russian invention. It was used in many ancient societies and cultures, including those without snow, such as ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

In Russia, sledges were the most popular transportation, including in summer, since there was no road construction yet (roughly, before Peter the Great) and, sometimes, it was easier to go on a sledge even in dry weather. As researcher of the history of sledges Mikhail Vasiliev points out, several hundred parts and details of sledges – and only a few details of carts – were found during excavations in Novgorod.

Tsar Ivan Vasilyevich on a sledge

Nikolai SverchkovSince antiquity, the sledge was considered an "honorable", high-status transport – after all, it was much calmer to travel in a sledge than on a wheeled cart, which shook and tossed from side to side on the Russian off-road. In the 16th century, English traveler Anthony Jenkinson wrote: "If a Russian has any means, he never leaves the house on foot, but, in winter, goes out on a sledge and, in summer, on horseback." As we can see, even in the 16th century, wheeled carriages were not yet so widespread, as they’re not even mentioned by Jenkinson.

An expensive city sledge

Kolomenskoe State Museum ReserveIn the northern parts of Russia, sledges were used almost all year round – there were a lot of bogs and hardly traveled roads. In the middle zone and southern regions, however, carts were still used in summer. But, the sick and ill were always transported everywhere in sledges. Prince Svyatoslav Vsevolodovich of Chernigov went to Kiev on a sledge with a sick leg in 1194, although the trip was in summer.

An old Russian sledge

Legion MediaSledges were also the traditional transportation of Russian Orthodox bishops. Even in the 19th century, according to life historian Mikhail Pilyaev, bishops traveled to church in sledges – carriages and ‘kolymagi’ (carriages without a turning mechanism or springs) were used by bishops only for trips to the court. For example, Metropolitan Pitirim, who lived in the 17th century, rode in a sledge pulled by one horse in winter and summer.

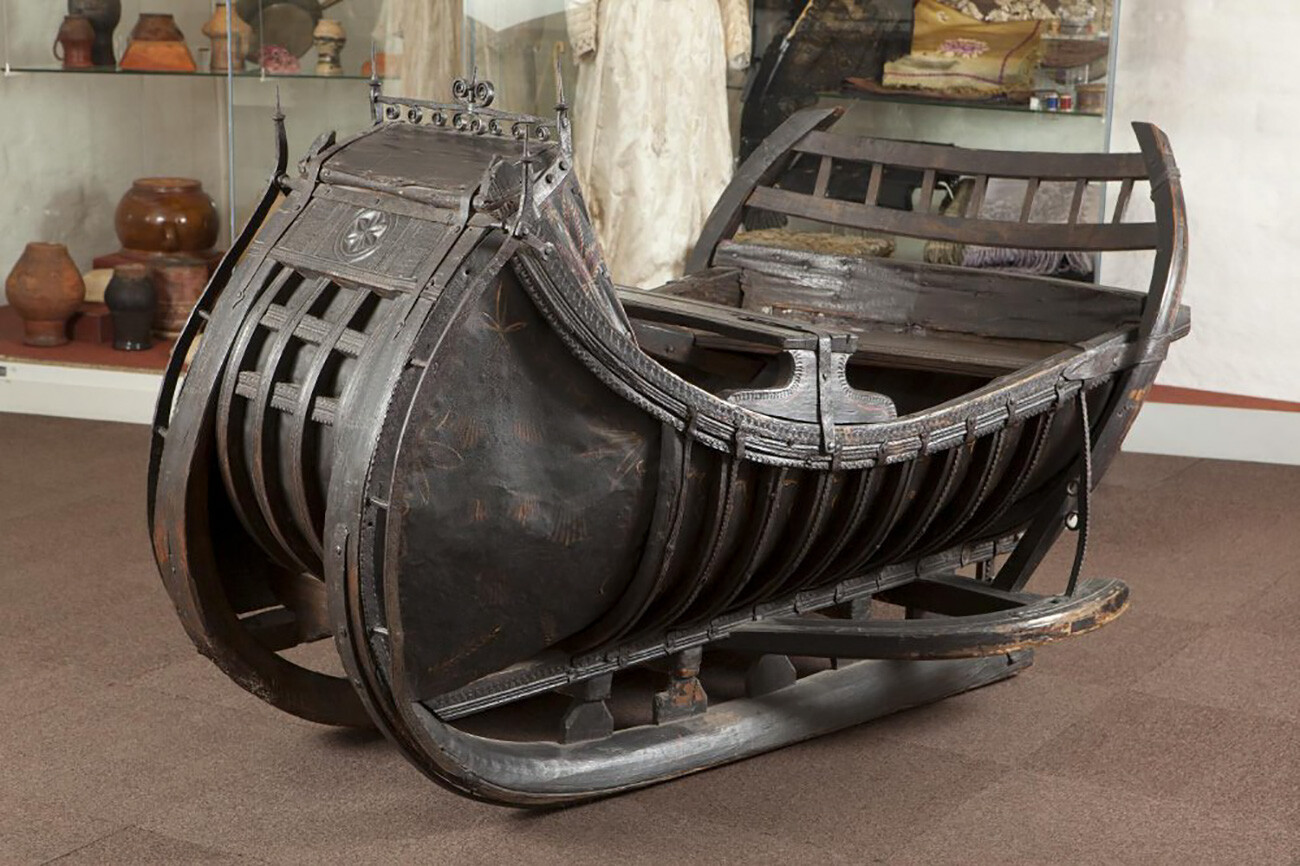

An expensive village sledge

Verkhoturye State Museum ReserveAll Old Russian sledges had similar construction. The runners were made of strong wood – oak, elm, maple or birch. The runners were also the most expensive part of the sleigh. In front, they were bent upwards, while grooves were made along the entire length of the runners, in which from 4 to 12 massive vertical bars of maple, pine or spruce were inserted.

A winter sledge carriage that belonged to Empress Elizabeth of Russia

Moscow Kremlin MuseumsThe vertical bars of one runner would be interwoven together by strong, thick branches of easily bendable tree species (cherry, willow).Two long, thick wooden bars were put above each vertical bar, which were called ‘nascheps’. Sometimes, they were connected with crossed wooden bars. And, now, the sledge chassis itself was placed onto the ‘nascheps’. The shanks, which the horse pulls, were attached to the first pair of vertical bars.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox