Why Russia has 2 calendars and how it lost 13 days of history

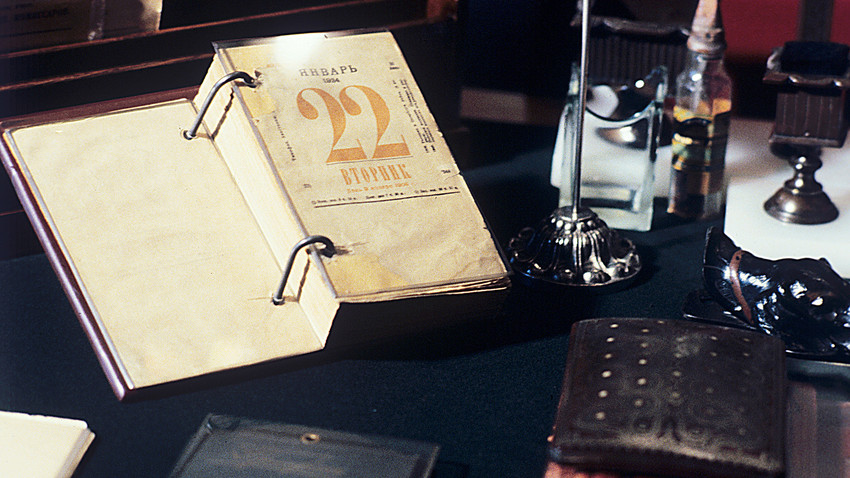

A desk calendar used by Vladimir Lenin in his Kremlin's apartment

Prihodko/SputnikAs you may have guessed, Russia switching to the Gregorian calendar from the old Julian is to blame. This happened three months after the Bolshevik Revolution in accordance with a new decree “on the introduction of the Western European calendar.” So right after Jan.31, 1918 came Feb.14: Two weeks of the year were simply written off.

As it was written in the decree, the document aimed at “establishing a time counting [system] in Russia that is similar to almost all cultural nations.”

From the early 18th century, since the time of Peter the Great, the country exclusively used the Julian calendar, introduced in Europe by Julius Caesar. It was less precise and by the year

‘Destruction of old habits’

The Bolsheviks considered other options on how to transfer the calendar from the old to the new, like cutting one day each year. However, they decided to speed things up a little and instead of waiting 13 years it was simply done overnight.

People gathered to read one of the decrees issued by the Bolsheviks, painting.

Public DomainAccording to the head of the Russian State Archive of Political History, Andrey Sorokin, the Bolshevik leaders had “clear and utilitarian tasks” [in changing the calendar]. “The Russian Revolution was perceived by Lenin as a prologue to world revolution. The hearts of proletarians of the entire planet were supposed to beat in unison and in accordance with one chronometer. Hence, it should be no surprise that this decree was adopted as one of the first [of their documents],” Sorokin claims (in Russian). The historian adds that this decision fits into the general Bolshevik approach facilitating the “destruction of old statehood, old traditional culture, old habits and norms of formal and common law.”

‘Untimely and improper’

Yet the calendar reform was not executed only because of the Bolshevik’s ideological inclinations. Suggestions of switching to the Gregorian calendar appeared in Russia as early as in 1830. The Russian Academy of Science proposed the introduction of a new calendar but encountered opposition from the minister of education. “[An] Untimely, improper [proposition] that can lead to undesirable disturbances and unnecessary minds’ tempting,” Minister Karl Liven said. Tsar

The next attempt occurred at the end of the 19th century. A special commission was set up by the Russian Astronomical Society, and the body’s conclusion highlights why the proposed introduction of the Gregorian calendar met such stiff opposition in Imperial Russia.

The commission outlined that “Orthodox states and all Orthodox people of the East and West reject the attempts of Catholic representatives to introduce the Gregorian calendar in Russia.” In other words, the calendar was perceived as some sort of Catholic sabotage of the Orthodox Church.

Two calendars in one country

The commission found an innovative idea, proposing to reform the calendar to make it more precise without importing its Western version. At the same time, another commission, in 1905, found the transfer to the Gregorian calendar “desirable” and offered a compromise: To use it in civic life and leave the Julian calendar for religious purposes.

In just over a decade this happened, as the Orthodox Church - with its strained relations with the Bolsheviks - did not want to capitulate to Western influences nor domestic nihilists. The Bolsheviks tried to exert some pressure (in Russian) - but it was all in vain.

Read here how the Russians celebrate the New Year twice.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox