5 exotic cults outlawed in Russia

Islamists, Satanists, and racist Neo-pagans - all of those are not welcome in Russia.

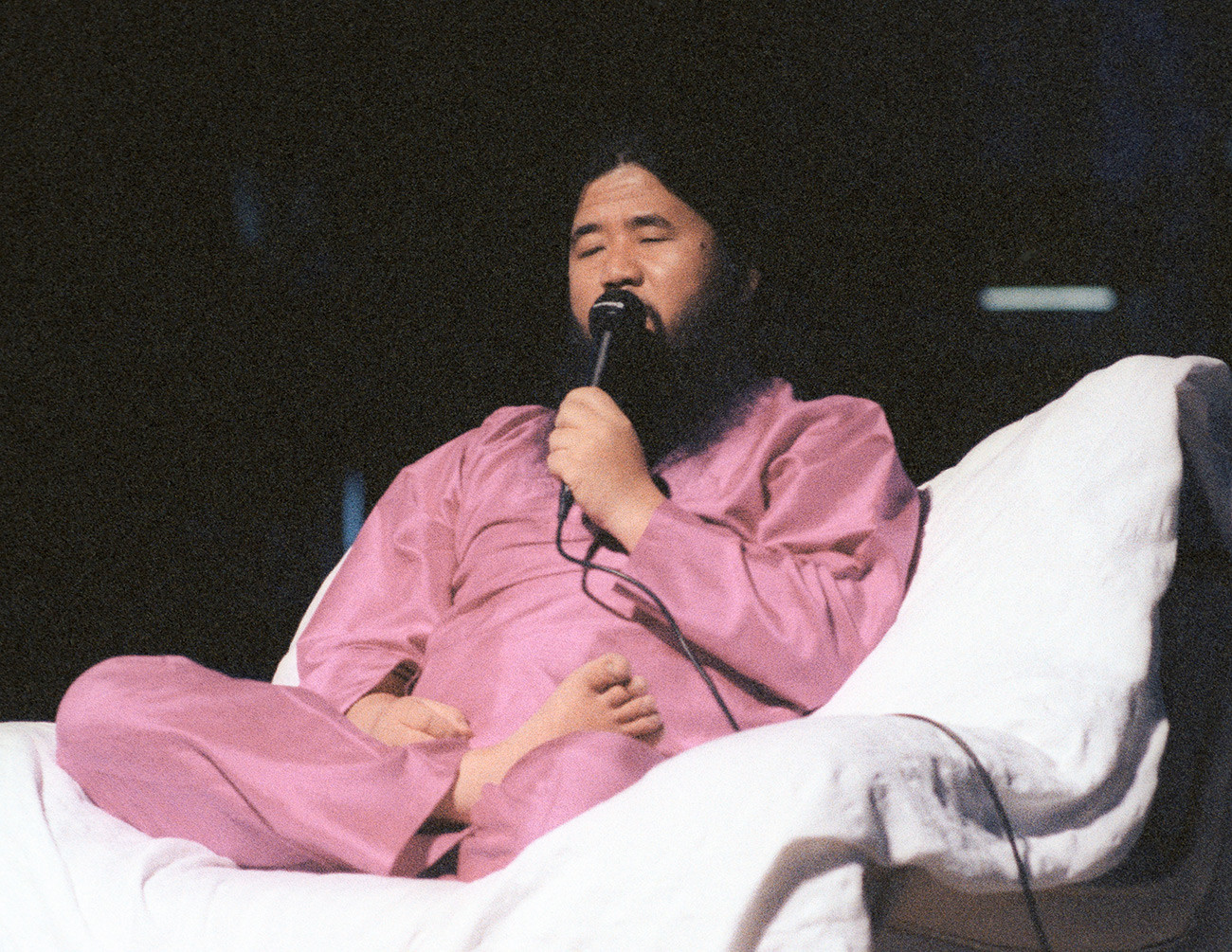

Reuters; Freepik; Getty Images1. Aum Shinrikyo

Sato Asahara, leader of the infamous Aum Shinrikyo cult, in Moscow, 1992.

S. Miklyaev, V. Zhukov/TASSOne thing Aum Shinrikyo, the Japanese doomsday cult founded by Shoko Asahara in 1984, is well-known for around the world is a horrific sarin attack in the Tokyo metro in 1995 that killed between 10 and a dozen people. What’s less known is the fact that earlier, Aum Shinrikyo had thrived in Russia and was almost as big as it was in Japan.

Russia witnessed the rise of the Japanese cult before the infamous attack – in the late 1980s – early 1990s, when the cult acted legally in Japan and all over the world. Aum Shinrikyo seemed to be a respectable organization; Moscow’s mayor Yuri Luzhkov even shook hands with Asahara when he visited Moscow in 1992. As RIA Novosti wrote, the cult had about 10,000 supporters in Russia and purchased weapons here for their future attacks.

Russian members of the Aum Shinrikyo movement meditating in March 1995.

Getty ImagesAfter Aum Shinrikyo committed the terrorist attack in Tokyo and Asahara and his henchmen were caught and sentenced to death, a Russian court banned the cult in the country – but it wasn’t included in a federal list of terrorist organizations until 2016.

To know more about the history of Aum Shinrikyo in Russia, read our special feature.

2. Jehovah’s Witnesses

Jehovah's witnesses sing songs during the meeting in Rostov-on-Don.

Getty ImagesPerhaps the least exotic one in the list. There were around 160,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia by 2017, the year this Christian cult was outlawed in the country. It came as a bolt from the blue: the cult had no history of propagating cruelty. Nevertheless, the Russian Supreme Court found the organization extremist and forbade all its activities in the country.

Jehovah’s Witnesses are different from the majority of Christians. They don’t believe in the Holy Trinity and are awaiting the imminent end of the world and a final battle between God and Satan to begin. They live by strict rules – for instance, they prohibit military service or blood transfusions. Nevertheless, many doubted if this cult really was extremist: among them was Russia’s President Vladimir Putin. “This is some kind of nonsense, we need to study this issue thoroughly,” he said in December 2018. However, so far all Jehovah’s Witnesses groups remain banned in Russia.

We also have a feature on Jehovah’s Witnesses and their prohibition in Russia in 2017 – feel free to read it.

3. Ancient Russian Ynglistic Church of the Orthodox Old Believers—Ynglings

Alexander Khinevich, the leader of Ynglings.

As SudarAlong with world-famous cults with hundreds of thousands of believers, Russia’s list of extremist organizations includes far more exotic organizations – among them, the Ynglings. They have “Ancient”, “Orthodox” and “Old Believers” in their official name – but they’re none of the above. This neo-Pagan cult was founded in 1992 in the city of Omsk (2,700 km east of Moscow) by Alexander Khinevich, who used to champion ufology.

Khinevich certainly took a lot from his previous hobby while writing his “Bible” – the Slavic-Aryan Vedas. The book mixes the idea of gods who came to rule Earth from space, ancient Scandinavian sagas (for example, Khinevich’s supporters believed Asgard, the city of gods, was situated where Omsk now stands), Slavic legends and a bit of good old racism. For instance, Ynglism forbids mixing races and regards the white race as superior.

That was why the state wasn’t fond of Ynglism and banned it in 2004 for “incitement to hatred.” In 2015, the Supreme Court also added Slavic-Aryan Vedas to the list of extremist literature. So it seems that during the last 15 years Khinevich was communicating more often with the police than cosmic gods.

4. Nobilis Ordo Diaboli

Alexander Kuznetsov, the leader of a Russian doomsday cult.

ReutersThis organization (‘The Noble Order of the Devil’) was a tiny Satanist cult from Saransk (650 km east of Moscow), whose founder, 25-year-old Alexander Kazakov, studied in the local university – except for when he was worshipping Satan and seducing the female members of his cult. The organization had between 30-50 members and performed quite ordinary Satanist routines like signing soul-selling contracts with blood and mass orgies. They remained active until 2009 when the police caught the leader and put him in jail for 20 months. So was the devil defeated in Saransk.

5. The Faizrakhmanist movement

A member of the Faizrakhmanist community.

Nikolai Alexandrov/TASSMany Islamist movements are banned in Russia as extremist but the Faizrakhmanist cult stands out even against such a colorful background. Its founder Faizrakhman Sattarov used to be a mufti in Tatarstan, when back in the 1980s he thought he was the Messenger of Allah – rasul, left traditional Islam and started a cult in a house he bought.

Several decades later, there were 64 people in the Faizrakhmanist movement, including 27 children: they all lived as a closed community of hermits in a building with eight underground rooms. This was Faizrakhman’s tiny ‘Islamic caliphate’. They didn’t act aggressively but definitely posed a threat to themselves as the leader forbade the members to leave the house, access any kind of medical care or education; children were not allowed to read anything but Sattarov’s works and the Quran.

After the authorities found out about the cult in 2012, they evacuated 19 children who required medical help and eventually forced the rest to leave; four people were charged with child cruelty and imprisoned. In 2013, the state banned the movement as an extremist organization.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox