From persecution to peaceful coexistence: How Catholics live and pray today in Orthodox Moscow

A traditional Christmas Eve Mass at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Holy Virgin Mary

Valery Sharifulin/TASSFor a passerby, the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Holy Virgin Mary, the largest Catholic church in Russia, emerges suddenly in the

Believers near the Roman Catholic Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception of the Holy Virgin Mary during Catholic Christmas celebrations in Moscow.

Ruslan Krivobok/SputnikSeveral people hurry to the church: The mass, the fourth this day, is about to start. For Catholics it’s especially important to attend church these days because it’s Advent, the season before Christmas when believers must especially dedicate their thoughts to God, pray and expect the birth of Jesus.

Those entering the cathedral see a big cross with the inscription: “Christ yesterday, today and always.” But it wasn’t always like this. For decades, Jesus and his worshippers weren’t welcome in the building at all.

Overcoming historical enmity

While centuries ago the two faiths were bitter rivals, today the differences between Orthodox Christian and Catholic Russians (about 1 percent of the country’s population) seem minor. Everyone who has ever been to an Orthodox church can recognize similar ceremonies in this Catholic cathedral that is full of Christmas trees.

Some outward differences catch the eye: Catholic women don’t cover their heads, people make the sign of the cross differently, priests are beardless and wear different clothes. Obviously, there are more serious contradictions: For the Orthodox, the Pope isn’t the head of all Christians, the two confessions disagree on the nature of the Holy Trinity, and etc.

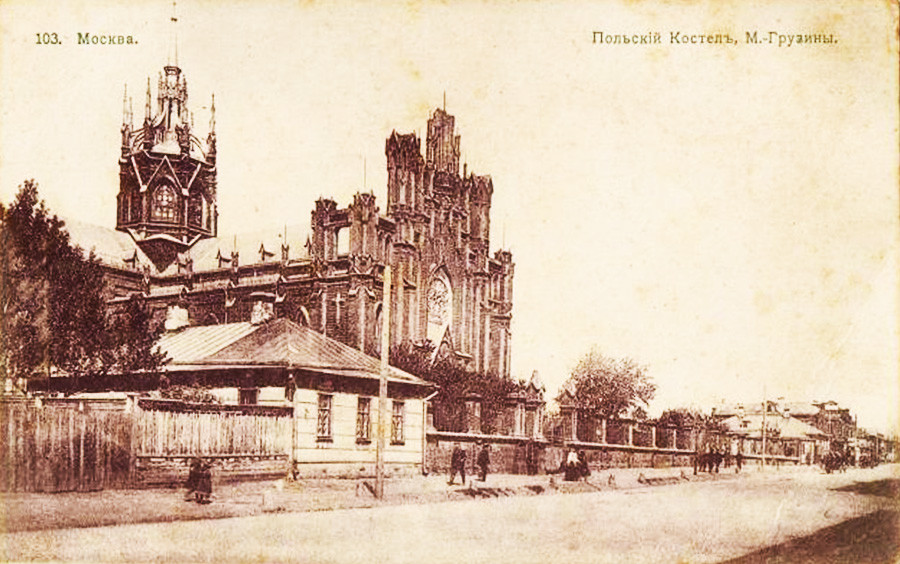

Catholic Cathedral Moscow Postcard

Public domainThe onslaught of secular modernity and competition from other religions, however, is bringing Catholicism and Orthodoxy closer. “We all are Christians and we should be closer to each other than to people of different religions,” said Igor Kovalevsky, the General Secretary of the Conference of Catholic Bishops of Russia, in an interview with Echo of Moscow radio.

Orthodox Metropolitan Illarion agrees: “Both our Churches are concerned with the same things: The crisis of morality in society, the high level of abortion and divorce, and a lack of social security.”

While relations today are warmer, in the past it wasn’t always like this.

A grim past

Predominantly Orthodox Russia acquired its Catholic minority in the 18th century after annexing large parts of Poland and Lithuania. “Historically, most Catholics live in the western parts of our country. Or, it’s connected with the sadder pages of history: Many Catholics were sent to Siberia from Poland, Lithuania, and Ukraine,” said Father Kirill Gorbunov, spokesman for the Roman Catholic Archdiocese in Moscow.

Orthodox Tsars allowed Russians the chance to convert to Catholicism only in 1905, and six years later the grand cathedral of the Immaculate Conception was built. But dark days soon set in. After the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917, the situation turned grim for Catholics and all religious believers.

Many Catholic churches were closed (including the cathedral), and many priests arrested. By the late 1930s, only two Catholic churches remained open in the USSR, both with the status as “French embassy churches.” As for the Moscow cathedral, it became a secular building with four floors that served as offices for state companies: a furniture factory, a lamp store, and even an alcohol bottling shop.

Only in the 1990s, after negotiations with the city government, and thanks to

New churches planned

Organ music and singing fill the cathedral, as several dozen people pray. Some sit on benches and others stand, constantly crossing themselves. The priest reads the Gospel in Latin, but five minutes after the Latin mass ends the Russian-language mass starts immediately.

“We have masses in Russian, Latin, of

Believers attend a traditional Christmas Eve Mass at the Roman Catholic Church of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Rosary.

Vladimir Smirnov/TASSIn total, there are only three Catholic churches in the capital. Besides the cathedral, there is the Church of St.

Who are Moscow Catholics?

Andrei, 25, sings in the church choir. He has Belorussian roots and used to be Orthodox, but then after scrutinizing different aspects of various confessions, he decided that Catholicism better suits his worldview, and so he converted. “I side with Catholics in all major issues, including the supremacy of the Pope,” Andrei explains with a smile.

According to Father Kirill, around 150 people are baptized into Catholicism each year in Moscow. This includes those converting from other religions, former atheists who found faith, and newborns in traditional Catholic families.

“Mostly, our parishioners are people of Russian culture, who speak Russian and associate themselves with this country,” Father Kirill said, adding that some had Catholic (Polish or German) origins, but other converts just chose this confession.

In many ways, Russian Catholicism has certain unique traits. For instance, Russian Catholics adore the ceremony of breaking bread on Christmas and other church holidays. “That’s what you hardly see in Catholic communities in Italy or Latin America; this is an Eastern European tradition,” said Father Kirill.

Also, Russian Catholics embrace several mostly Orthodox traditions, like strict fasting during Lent and Advent – while in the West that’s not necessary. This comes as no

Doors open for guests

Though the Catholic Church in Moscow is small, both priests and parishioners are always ready to welcome foreign guests – expats living here, or anyone visiting the capital for a couple of days. In Moscow, you can find different Catholic communities, including not only Europeans but also Vietnamese, Korean, Filipino and so on.

“Our main mission is connecting people with God, but we’re happy to connect people with each other as well,” Father Kirill comments. The Church unites everyone, and a foreign student attending mass in one our churches might see the ambassador of his country sitting next to him. Why not?”

You can start exploring the small but proud world of Catholic Moscow on the website The Catholic Travel Guide, where addresses and service schedules are listed. Good luck, and Merry Christmas.

If you want to know more about Christmas in Russia, read our article on how Russian Tsars used to celebrate it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox