3 very real tales about working in the USSR

1976: Petya ‘Gillan’, 28, street hustler; Boris, 24, unemployed

Gillan parks himself on a bench by the Pushkin monument, lighting a cigarette. Boris joins him.

– Hey, what’s up man, you Gillan by any chance?

– What do you want?

– I’m Borya. Kostya Old sent me.

– Oh, him. What’s going on man, yeah, I’m Gillan.

– Listen, so Kostya told me you’re the man to ask about making some money…

– Yeah, I’m the guy. I was actually just looking for someone to go on runs over to an utyug [flatiron in Russian].

– I’m good for it, just say what you need me to do. I’ve had about enough of this sh*t… parents

– I’m digging the enthusiasm, pal, you and I both know you can’t stay jobless, they’ll have you arrested on a 209 [‘parasitism’, according to the Soviet criminal code]. It ain’t a pretty picture: someone at the komunnalka rats you out for sitting on your ass all day, drinking, bringing home broads – the law’s gonna have you like a dumb little pussy. And you will work, trust me. ‘Cause if you don’t, it’s bye–bye freedom. Remember that poet, Brodsky, from Leningrad? They had that clown on parasitism back in the 60s… poor bastard had to do hard labor up north – believe that sh*t?! So you best make nice by your folks and be a good little boy, get a job as a lab assistant at some institute, and just show up once a week or something. And if they ask where all that money’s coming from, just tell ‘em you found a good score.

– OK, but will there actually be money?

– Alright, look here… if you head down the street right here, you’ll eventually get to the ‘Inturist’ hotel. Enter the lobby and you’ll see these dudes all dressed up fancy. Approach any one of them, and they start addressing you in English. Those are the flatirons (utyugi) I was talking about. They stick to foreigners like glue.

– And what are they supposed to sound like…?

– Well [in English], “hello, mister, maybe you need rare Russian souvenirs? Coins? Matryoshka?”...that kinda stuff. You get the point that a lot of foreigners are here on business, right? They’ve got their entire day planned out, and they’re being driven around town. Thing is they’ve also got the KGB on their tail 24/7. You can imagine, there’s no time to so much as visit a shop, get some presents. They even have to fill out forms when receiving Soviet money – and you can’t exactly buy anything using dollars, right? That’s what the flatirons are there for – and everybody’s happy: our guy gives him some sh*tty matryoshka, maybe even a Nicholas II-era ruble, or an old bracelet, and the American hands him his leather jacket. You see, back home, he’s gonna get that jacket in a matter of minutes at some ‘municipal store’ – or whatever they call ‘em. The utyug, meanwhile, can sell that jacket for a whole fortune over here – it’s all good brands after all! I mean – these guys’ll take anything – cameras, cassette players, shoes, watches, umbrellas… don’t forget about bubblegum and cigarettes! We’ve got foreigners bringing stuff into the country deliberately… I mean – where else are you gonna trade a pair of shoes for a freakin’ Romanov dynasty relic?

– The Romanovs?!

– Sure! That’s what they’ll tell you! These hustlers scam foreigners like nobody’s business. No principles, these people. And that’s how it goes: hotels, train stations, airports – they’re everywhere…

– What, all in plain sight of the militsiya [old word for police]?

– Well, the militsiya gets its cut – and it’s a good cut. This isn’t exactly legal, after all. But once you move up into the big leagues and trade currency, it’s best to avoid them altogether. You know as well as I do – currency speculation is certain death by firing squad. These guys won’t be caught dead trading. And that’s where you come in. You hook up with them, they give you the parcel, bring it to me, and I handle the sales, I’ve got people for that.

– So, anyway, what’s up with “Gillan”?

– I’m a big fan of Ian’s. Got a legit pressing of Jesus Christ Superstar, a buddy hooked me up, he’s a conductor on the Moscow-Berlin train. Which, by the way, is an awesome gig these days… So, anyway, Borya, why don’t you come by, we’ll have a listen to Superstar and a drink and talk business. Alright, time to wrap this up, there’s a patrol car over there, see the one – checking these long-haired dudes for their IDs?

1973: Aleksandr, 38, manager at the Ministry of Electricity; Elena, 36, factory worker at the Ministry for Non-ferrous Metallurgy

It’s Saturday evening. Aleksandr and Elena are sitting in their room at a communal flat, getting ready to go visit friends.

– Hey Sasha… Sasha! Why do we have to go to your boss’s birthday party? You see the man practically every day…

– Lena, you’re an adult, don’t you get it? It’s all about who you know in this country – nothing ever happens without connections! If I don’t sustain a close relationship with management, I can kiss my career goodbye! My department didn’t make the quota for the last quarter. You know Mironov, right? The guy from the other department? Well, he got expelled from the Party yesterday for that very crime! And demoted as well… now his deputy’s the one giving him orders! And you know why that happened, right? It’s because he didn’t come to Petrov’s last birthday bash, didn’t even present him with a nice bottle… by the way, you

– They’re right there, on the closet. Sasha, you’re at the office every day, and you haven’t been tardy once in 10 years! You’ve been at that place since the Khrushchev times, remember? Each day feels like the army: office at 9, lunch

– It’s always complaining

– I do know, you remind me on a daily basis. I’ve been leaving the office at 9 all of last week… and what are my heels doing on the bottom shelf again? I’ve asked you a hundred times – you know they get covered in

– And why did you have to work late anyway?

– What do you mean “why”? You don’t remember me taking three sick leaves in a row? Now I have to show “will and determination” – as my boss puts it, or she’s gonna have my behind at the monthly Party members meeting… I can’t handle another one of those!

– Alright, all set? Let’s go. Where are the keys?

–

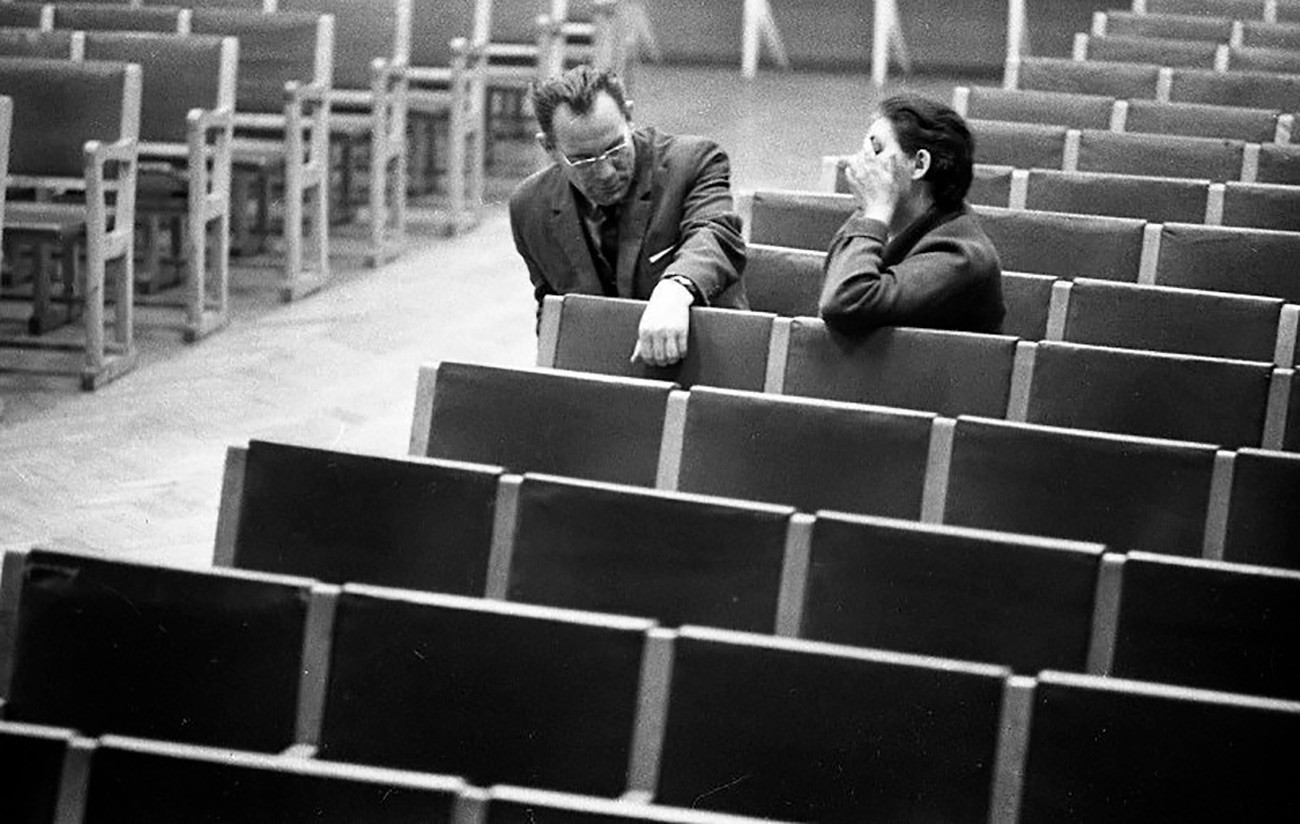

1981: Viktor, 34, artist/painter; Andrey, 22, student at the Surikov Institute for the Arts

It’s a hot summer’s day. Viktor and Andrey are at Viktor’s workshop, drinking port.

– So, you brought the port, Andrey, but have you got the snacks?

– Yeah, here’s the baloney…

– God almighty, whoever has baloney with port?! You’re a shining example of

– Which one? The junior membership at the Soviet Artists’ Union? I got in. A lot of us did – I mean, you have to work don’t you. Just tell me this – what’s the use anyway?

– What do you mean? The sooner you start exhibiting your work, the better of course! Why do you think all of that needs doing… it’s so so you get your own exhibits. That’s how a painter’s worth is measured in this country – the number of exhibitions they’re able to put up. You gotta have at least 2-3 every year, whatever the cost. Plenty of halls for that as well.

– Wait, and how am I supposed to paint that many paintings? 2-3 exhibitions per year? That’s insane.

– Man, don’t you get how this works? Those aren’t personal exhibitions – but group ones… students like yourself. Look outside, you’ll see placards for that kind of thing: ‘an exhibition of student works’... 15-16 per year, that’s what you gotta do, 2-3 paintings for each one, and you’re good.

– Viktor… can you count?! 3 works per 3 exhibits – that makes 9. What about the rest?

– What is wrong with you, buddy? It’s not like you can hope to showcase each painting. They’ve got to be accepted by the committee first. They might take half and throw out the others for “conflicting with ideology”, you know the score, Union people are all Partymen! So, if you’re not a Rembrandt, pick something ideologically fitting… Take me, for instance, I’ve got my

– I see that port’s taking effect nicely. So what, you’re saying you’re gonna be doing Lenin and peasants until you drop dead?

– What else am I gonna do? It’s not like either of us is in a hurry to get an actual job – we want to be “free”... artists! So, do yourself a favor, and stick with the youth program. And then, in four years’ time, once you’re done with university, you’ll enroll in the adult department. They’ll sort you out with a membership program at some painters’ plant, and off you go, constantly receiving orders for new works, picking up checks at the cashiers’.

– Speaking of money – where does it all come from?

– It’s, the Painters’ Union of the USSR, pal! A state body! The Houses of Culture themselves don’t do the paying, they’re just issuing requests for this or that job, while the Union then distributes them. It all comes from the budget. Who do you think funds our work-related trips?

– You mean your work-related trips… you’re the one with the workshop…

– That’s right, pal. You gotta set yourself up for success! Got my workshop now, been at it for four years. 25 square meters – and a Garden Ring view… I’m rolling in luxury! As far as creativity goes [approaches an easel and removes the drape]...

– Oh, I’ll say! What breathtaking scenery…

– That’s right. Something I wouldn’t be ashamed of hanging up on my own wall.

Editor's note:These fictional conversations are based on actual interviews and memoirs.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox