10 things you can only understand if you lived in the USSR

1. Drinking “mushroom tea”

In many Soviet apartments, the older family members often advised young ones: “Drink mushroom tea, it’s good for your health.” In the kitchen or on the window-sill, a jar often stood containing a jellyfish-like entity floating in brown liquid. Kombucha (“mushroom tea”) is a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast, floating in sweetened black tea, which it uses as a nutritional source. After some time, the colony turns the tea into “mushroom tea,” a bittersweet sparkling drink resembling kvass and containing a bit of alcohol.

In the USSR, kombucha was purported to heal all kinds of diseases, from AIDS and cancer to grey hair - though none of this has ever been proven. With long queues in hospitals and medicines hard to get, Soviet people often embraced various pseudo-medicinal recipes, and “mushroom tea” was one of the most popular home remedies – not to mention a way to pass the time. Not long ago, Russian arms dealer, Viktor Bout, cultivated “mushroom tea” in his prison cell in the U.S. – but his kombucha was confiscated on the grounds that it contained alcohol.

2. Carpets on walls

Carpets and rugs are made for covering the floor, right? Think again. In Soviet apartments they hung on walls and we're treated with great respect and care. In fact, carpets and tapestries have been covering the walls of wealthy Russians since the 17th century, and have been a sign of prosperity. For Soviet people, however, carpets served as both heat and sound insulation in low-class residential buildings, where most of the population lived.

3. Soda siphon

Siphon, a device for dispensing carbonated soda water, was created in 1829 in France and was very popular in Europe before World War II. The war, however, destroyed most siphon production plants in Europe, and then bottled carbonated beverages became popular everywhere, except in the USSR where buying bottled water was very expensive. It was much cheaper to buy a siphon and then replenish it using little cylinders containing carbon dioxide.

There was another use for a siphon – one could carbonate vodka. During Gorbachev's alcohol prohibition, people desperately sought ways to increase the potency of alcoholic drinks, which were hard to find and expensive. Carbonated vodka had a quick effect on the body because bubbles are absorbed into the bloodstream much faster, just what hard-drinking workers wanted.

4.Mittens on a rubber band

Nothing beats warm woolen mittens when it’s biting cold outside. In Soviet Russia, however, you couldn’t just buy new mittens if you lost them, especially in small towns and villages. For sure, any babushka could knit new mittens, however, wool was often in short supply. So, mothers took a rubber band and sewed the mittens at both ends so that the band passed through the sleeves and through a stitch in your overcoat near the back of the neck. Then, the mittens would hang down from the sleeves even if you took them off. This 'know-how' was familiar to any Soviet kid who loved to play outside in winter.

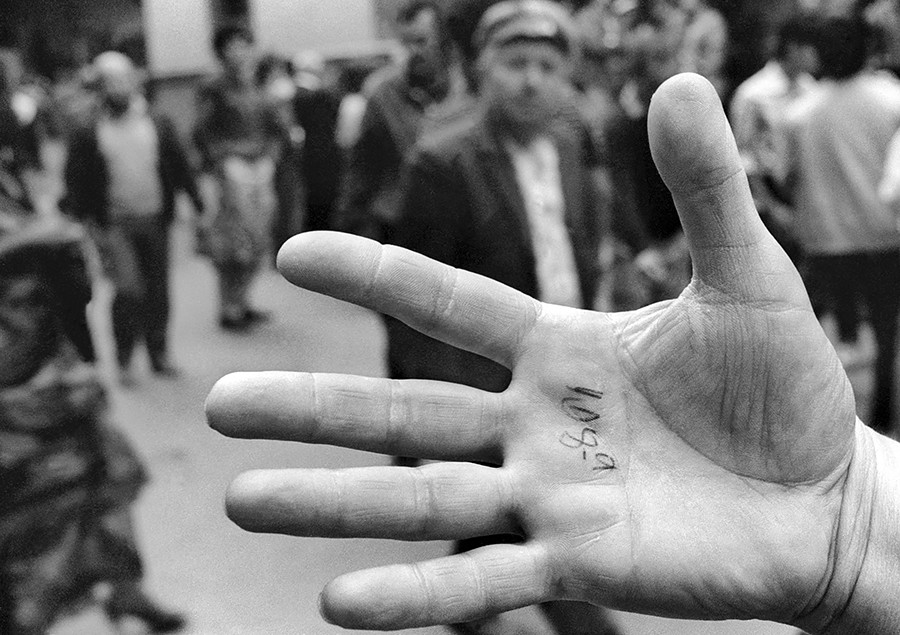

5. Numbers on your palms

No, this is not about prisons. Instead it’s about waiting in lines, which took up an enormous part of a Soviet citizen’s time. When there were shortages of consumer goods - be it furniture, house appliances, fresh meat or fruits - it was certainly worth standing in line for the chance to buy something scarce. Sometimes there were multiple queues for different goods, especially in big department stores. People had to “register” in these queues. In each line, there usually was an unofficial numbered list of people, and with the numbers written in pen on palms. If you were lucky, you could be “registered” in two or three lines simultaneously, and in one evening have the chance to buy a pair of shoes, fresh oranges and a bottle of good wine; not to mention end up with a dirty hand from all the ink.

6. String bag

A string bag, made of simple rope, takes up little place in your briefcase or handbag, but it’s super handy if by chance you came across scarce goods on sale. In the USSR, this bag came to be called avoska, which derives from the old Russian word avos, which can be translated as, “What if?” Remember, you couldn’t buy a plastic or linen bag in department stores – none were on sale. With avoska everybody could see your purchases when you commuted home. “Comrade, where did you get hold of those… oranges, shoes, frozen fish, canned fruits, and so on?” a passerby would ask. And you’d duly report the location – this was a means of mutual support.

7. Soviet recycling: paper and glass waste

Recycling in the USSR was organized by the government. Schools held compulsory competitions for wastepaper collection. For adults the state offered a type of coupon that allowed one to buy great works of literature in exchange for wastepaper. For example, hand in 20 kilos of paper and you could get a single volume in the full collection of Alexandre Dumas’ complete works.

Recycling glass was big business in the USSR. You rarely found broken glass on streets because it was profitable to bring it to recycling centers. A redeemed milk bottle could get you around 0.15 ruble – a value more than the milk itself. One just had to wash the bottle and remove the labels. The bottles were not crushed, but reused, and often were accepted in the same stores where the drinks were sold. So, collecting bottles became a source of income for many Soviet citizens, even those not very poor.

8. ‘Sausage trains’ and ‘sausage platforms’

“What's long, green, and smells of sausage? – A suburban train,” so went a Soviet joke. But why? Before major holidays, such as New Year's Eve or the May holidays, festive foods were scarce, especially sausages, which was a staple for any holiday feast. Only in big cities could one get hold of fresh meats or sausages. So, as the holidays approached, early morning suburban trains were filled with people going to cities to stand in long lines for festive foods. To accommodate the excessive number of passengers, trains were extended with extra cars, and the platforms of some stations was also extended to welcome such trains – hence, “sausage” trains and platforms.

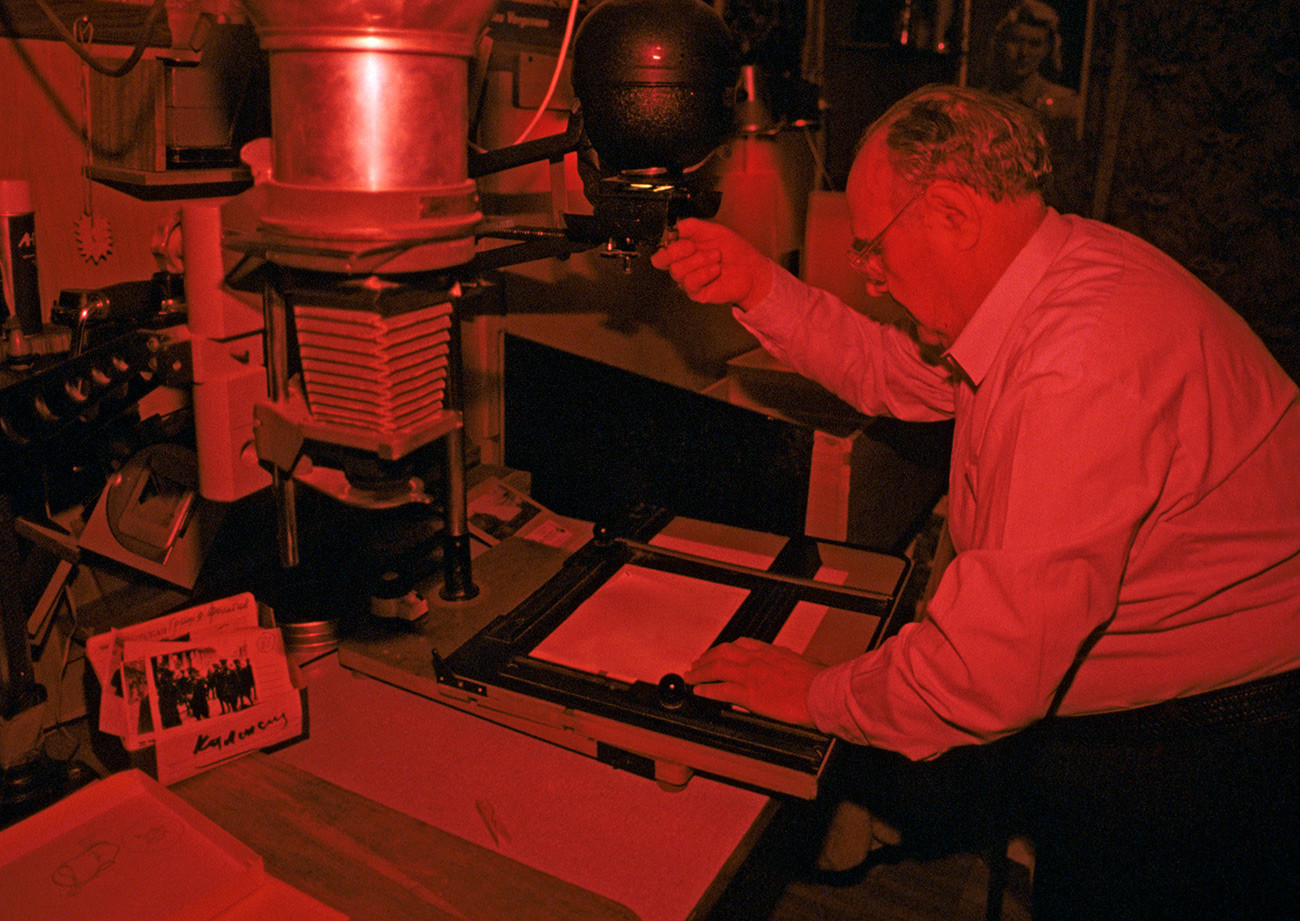

9. Red light in your bathroom

This has nothing to do with a red light district. Instead, if you were spending hours in your bathroom with a red light on, then it meant you were an amateur photographer. While photography was one of the favorite hobbies of Soviet youth, it was costly to develop your film in a professional photography studio. Armed with simple tools, as well as fixer and developer solutions, and using a red lamp to provide light, amateur photographers created visual histories of their families, which were carefully preserved in old-fashioned photo albums. These albums also became a special aspect of Soviet life - in awkward social situations, such as when meeting your boyfriend's parents for the first time, out came the albums that served as a good way to pass the time.

10. 'Music on the ribs'

Most foreign music records were banned in the Soviet Union, and were derided as “imperialist.” The Soviet government didn’t want their citizens to listen to “freedom-induced” rock-and-roll, jazz and what not. New records by The Beatles or T-Rex could be acquired only on the black market at enormous prices. Since demand was very high Soviet bootleggers devised an ingenious way to satisfy it - “printing” the records on obsolete X-Ray images procured from hospitals. These were primarily lung X-rays, depicting a man’s thorax, which is why it was called “music on the ribs.” X-rays were cut into the form of 7-inch disks, and the music was recorded onto them with machines converted, apparently, from old phonographs. The quality was awful, and such a “disk” could be played no more than 10 times. It cost a ruble or two, while new foreign vinyl could cost as much as 80 rubles (a month’s salary). These 'ribs' were sold at underground markets and were easy to hide in your sleeve.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox