52,000 tourists expelled from seaside Sochi in one day. Say what?

What happened?

Russians must self-isolate, it was announced by President Vladimir Putin in a special address to the nation on March 25, which means a week of sitting at home. “The safest place to be now is at home,” he said. As such, the week March 30–April 5 will be, for many, fairly inactive. It was assumed that this anti-coronavirus measure would reduce the number of people on the streets and in public transport, and everyone would obediently stay at home and read a good book. Dream on.

The news of the unexpected “vacation” was seized upon by thousands of happy Russians eager to sit out the quarantine somewhere warm: that same day, hotel bookings on the Black Sea coast, especially in Sochi, increased threefold.

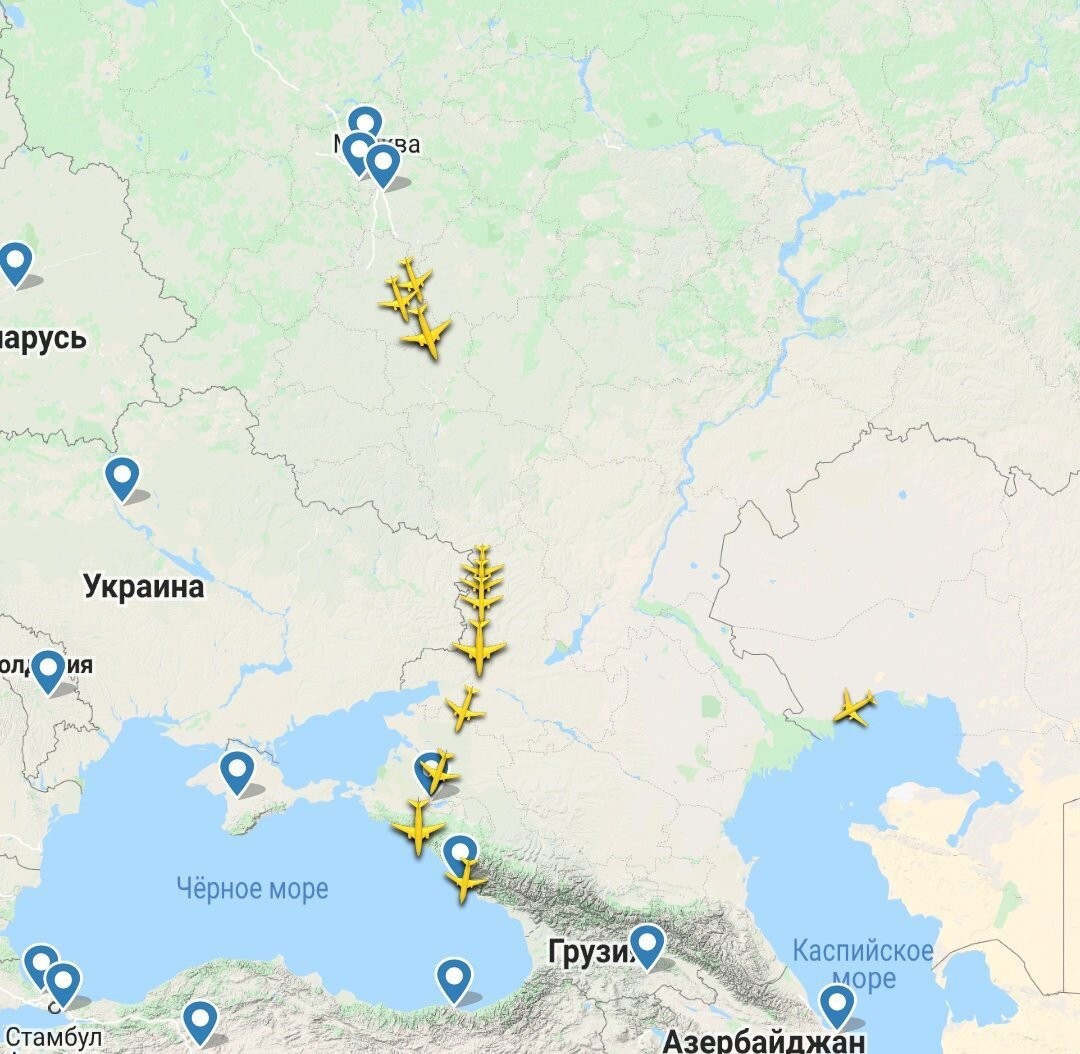

Airlines also played a part. Just days before, Aeroflot had slashed prices on domestic flights by 40-60% to attract passengers no longer able to travel abroad. Other carriers followed suit. As a result, by Friday, March 27, 52,000 tourists had assembled in Sochi, among them only 200 foreigners.

Mid-air about-face

But the tourist paradise didn't last long. The governor of Krasnodar Krai (which includes Sochi), Veniamin Kondratiev, alarmed at the stampede of tourists, urged people not to come and closed down all entertainment in the city, including concerts, amusement arcades, nightclubs, and movie theaters. All restaurants, cafes, bars, malls, leisure centers, and even parks were also ordered to shut up shop for this period. The only thing that tourists were allowed to do was go for a walk — around their hotel.

But the most radical measure of all was the ban on all new bookings — the governor simply forbade hotels from taking reservations. “Tourists already at hotels and sanitoriums will not be evicted. But starting March 28, no newcomers are allowed,” he stated.

The consequences came hard and fast as operators canceled tours left, right, and center. For example, a plane carrying 147 tourists from Perm to Sochi on March 27 had to turn back in mid-air when the operator promptly canceled the package tour and the chartered flight that went with it.

Despite all that, a significant mass of tourists did not heed the call and made their way to Sochi. “Well, what was I supposed to do? The hotel and round-trip tickets were paid for. And then we get told not to show up,” wrote Vitaly Demeshev in social media, one of the many who defied the ban.

No room at the inn

Many hotels, contrary to the government order, decided not to order guests to self-isolate, but to turn them out. The evictions began in the middle of the night, regardless of the date of their return flight. “About 3,000 people left the hotel that night. The rest, another 3-4,000, have to leave by 12 noon,” wrote Sergey Sergeyevich on Instagram.

One tourist told how hotels had stopped providing food: “This morning my mother and child went down to breakfast, which was prepaid. A security guard was sat there — no breakfast. They asked if food would be brought up to us and were told there weren’t enough boxes. They didn’t set up a hatch for serving food, didn’t take food to people’s room, didn’t return our money, didn’t put food on plates and leave it out for us. Nothing. Just a message at 4am from the tour operator saying that we had to leave on March 28.”

Evacuations home were arranged only for those who had bought a package tour, that is, flight and accommodation. Those who hadn’t were forced to fork out for more tickets, but this time the price was way higher: tourist Yana Pardo told Interfax that she had bought a ticket from Moscow to Sochi for 6,000 rubles ($75), but the flight back was 32,000 ($400).

The city administration announced that most tourists had agreed to leave Sochi of their own accord. Those who couldn’t or wouldn’t go were, in the end, allowed to stay in their hotels for a few more days at no extra cost — and with no food either.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox