The Russian streamer who plays games using his FEET

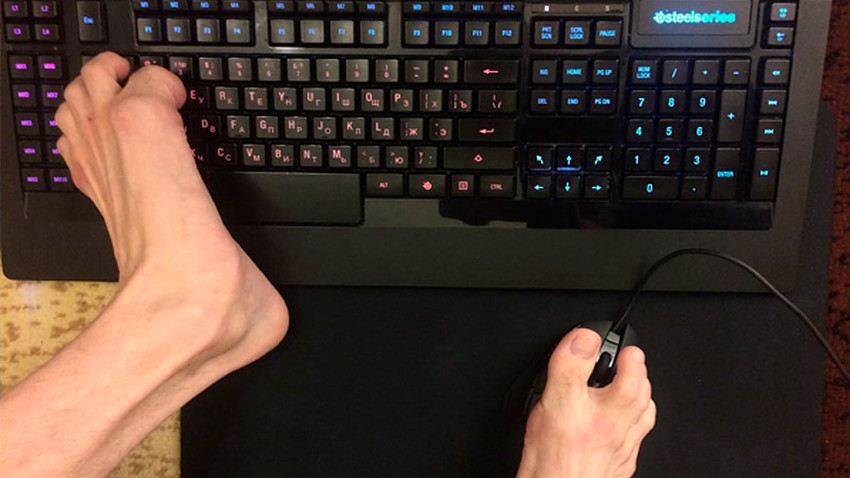

Viktor found his first days of streaming difficult. It was not easy to summon all his courage and emerge from the psychological comfort zone he had got used to over the years. He turned on the camera and directed it at his feet. One foot hugged the gaming mouse and the other started sliding across the keyboard. The movements were familiar. What was unfamiliar was that someone was watching him.

“I also wanted to know how the people whom for many years I had had the privilege of calling my friends would accept the truth,” he recalls, a year after his first stream on Twitch.

He had never met these friends in person. They had never heard his voice. Many of them didn’t even know what city he lives in. “500 km from Moscow. In which direction is not that important,” he tells everyone. Because, by and large, he simply fears that people, with the best of intentions, will try to persuade him to meet up in real life. “I am not ready for it at all,” he admits. It was also the first time that many learned that 30-year-old Viktor has cerebral palsy and that he works, communicates and streams video games using his feet.

‘I spent the first 10 years of my life in hospitals and pressure chambers’

Cerebral palsy can manifest itself in different ways and affects different parts of the brain. The symptoms of this congenital disease can cause motor impairments, mental disorders, or both. As borne out by statistics, the disease is diagnosed in two per 1,000 births, and 30-50 percent of such babies are mentally disabled. Total lack of control over the hands, an inability to walk, defective speech - these are Viktor’s symptoms. At the same time, his thinking processes are unaffected. “At least in something I was lucky,” he says ironically.

For the first 10 years of his life, hospitals and clinics were his home. Hospitals in his own city and region, hospitals in other cities, and one clinic abroad. Acupuncture, pressure chamber therapy, tons of tablets and the not always tactful behavior of doctors were all part of the deal. And, despite all this, Viktor had been growing up all this time not thinking that his general abilities were limited in any way. “I had real friends, independent walks outside and very many other things that my peers did not have. All my childhood, I cared about the same things that others cared about: The Terminator, Star Wars, Pokémon, pretending sticks were lightsabers, Harry Potter and how much Coca-Cola there was left in the fridge. How my parents managed all these feats at a time when they themselves were still yesterday’s children in the realities of the 1990s is anyone’s guess now,” he says.

And one day, the first game console - Sega - came into his life. It was a present from his father and someone had the logical idea of putting the joystick at his feet. He had already been doing many things using his feet for several years by then - for example, operating the TV remote control or assembling LEGO. Sega was followed by PlayStation, and then a PC appeared in the house. Before online games, gaming had been just one of his pursuits. But the renowned ‘Lineage 2’ game changed everything.

Two of his peers in the Far East told Viktor about it. But there was a problem - limited bandwidth that didn’t allow him to download the game in full. Sending his parents to look for a specific client version to match the server that his friends used for gaming didn’t seem like a way out of the situation either. So he told the friends about it and they recorded the client on a whole bunch of blank disks and sent them in a parcel to Viktor, 8,000 kilometers away. He received it.

“For the first few days and months, I just went crazy from a sense of freedom, something that until then I had felt only when playing GTA. The fact that you are surrounded by live players only made the feeling many times more intense,” he recalls.

And then the virtual world started pushing out the real one.

‘It's indescribably important to feel you're like everyone else. It’s possible in the virtual world’

The most difficult thing was explaining to everyone around him why he spent so much time in this virtual world. For other players, Viktor was a nerd wasting his life on some Korean trash that had no sense or tactics. For people in real life, he was a person getting over excited at the siege of a non-existent castle (in other words, roughly the same). To Viktor, it was all different.

“Personal interactions, a whole list of friends on each server, knowledge of the entire politics of clans and alliances but, most importantly, real people around me all the time. At times, I would just stop in cities, reading the dialogues of random strangers, and doing it for days on end.”

There was one important condition - full anonymity. “So that people would think that they were dealing with someone like them. In my situation, feeling that I am no different from others is indescribably important.”

Initially, in 2003-2009 it was very easy to stay “one of many” since essentially everything on the internet was based on text. Then, with the advent of voice chat, it became more difficult. “As an excuse, I used to claim I had no microphone. In almost every game I had trusted people who would use their voice to placate the most intrusive people who were trying to persuade me to buy a microphone.” With time, Viktor became bolder and started saying that he was silent because of his health condition.

Streams, love and lifelong self-isolation

His first stream on Twitch was mainly for his friends. They got together at short notice, spreading the word about the stream in their communities, no matter how long ago they had last been in touch: Viktor hadn’t chatted with some of them for years. “Unexpectedly for me, I got a lot of support. Seeing their reaction, I realized I had found my calling, no less. It was a great opportunity to challenge myself.”

Now he has a streaming and gaming schedule. Each session lasts a maximum of five hours. In the left corner of the screen is the warning: “Streamer without voice, chat only :)”, and above it: “Can’t use hands”, while on the right is the ‘donations’ target: “For my girlfriend to come over”. Out of the 15,000-ruble (approx. $210) target, only 3,400 has come in so far. Viktor found his girlfriend after he began streaming - they met during an Overwatch game transmission, and did a couple of joint matches. She lives 3,000 km away. They’ve seen each other twice, and saw in the last New Year together. He thinks he’s been incredibly lucky.

Viktor says that, for all the support he gets from viewers, streaming can’t provide a livelihood - he doesn’t have all that many followers; newcomers often watch for 5-10 minutes and don’t come back. So he makes extra money as a freelancer, writing articles for gaming portals, and in the future, intends to try his hand at software testing.

“Different transmission formats have been and will be on trend. Being a foot gamer is clearly not enough in itself to maintain an audience,” he says, and admits that he realizes full well that what he does is not even unique and there are many streamers on the internet with restricted physical abilities. One of the most striking examples is Michael ‘Brolylegs’ Begum of Florida, who plays in online Street Fighter tournaments using just his mouth. But Viktor does not understand why foot gaming is often less highly regarded than the game of a streamer who spends three hours making faces. People who chat with Viktor occasionally ask him to vary his game by at least trying to say something, but Viktor refuses to even show his face.

“What is more, the problem now isn’t any fear of haters or of not being accepted for the way I am.” Viktor has virtually no haters, and here, too, he has been lucky. “The behavior of my facial muscles very much depends on my emotions. Because of the difficulty I have in controlling them, there aren’t all that many acceptable angles of me.” And he also doesn’t want people who are close to him to see what can happen when he gets excited. “To speak, I have to use up all my concentration. I don’t think the possibility of losing my breath attempting to talk on a stream is a good idea. I doubt anyone would like to hear it.”

He knows that people leave the site because of the absence of a voice commentary (ultimately, streamers gain a following because of their individuality, and not the speed at which they get through games). But he doesn’t know what he can do about it yet. Subscribers suggest he should start coloring his feet and provide a bit of “cosplay”. Viktor promises to think about it. He invariably responds to every comment with the words “Thank you for your support” or “Take care”.

He has hardly left the house in the past seven years. He’s heard of the novel coronavirus and the pandemic, of course, but it hasn’t changed anything in his own life. It is hard for him to understand why people have found it so difficult to stay self-isolating at home when he has been in voluntary isolation from the real world almost his whole life, and never gets bored if he has at least a book in the room with him. But if you ask him what he would wish for if he had a single wish and it was 100 per cent certain to come true, he says: “It wouldn’t be an amelioration of my physical condition.” Because, firstly, there are people who face much greater adversity and he doesn’t complain about his lot, and, secondly, it’s all “trivial stuff”.

“I think the world has missed out on a lot of fine things that never saw the light of day because of someone saying: ‘You won’t succeed.’ So my wish is that people should believe more - believe in themselves, the ideas of their friends and those close to them. You might say, of course, that it's all rather naive and idealistic, but in actual fact it's really important. I’d really like people not to be afraid of living the way they feel they need to.”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox