Why Moscow is the greenest city in the world

A house at Nezhinskaya street, Moscow

stroi.mos.ruAccording to WorldAtlas, 54 percent of Moscow’s territory is covered by public parks and gardens, making it the greenest city in the world.

There are 20 square meters of trees and shrubs per inhabitant in Moscow – many times more than in Tokyo, London or Beijing. This happened because of the combination of two factors: first, Moscow was initially built amongst the forests of the North-Eastern Russia, second, landscaping and greening started in Moscow as early as the 18th century.

Fortress on a forest hill

Apollinaryi Vasnetsov. The Trubnaya Square in Moscow in the 17th century.

Muesum of MoscowBorovitsky hill, upon which the Moscow Kremlin stands, is named after the word ‘bor’ – ‘forest’ in Russian. And indeed, in the 11th century there was an oak grove here, where the central streets of Moscow are now. Another example is the Church of St. John the Evangelist under the Elm Tree, now on Novaya Square, not far away from the Kremlin. Historian of Moscow Pyotr Sytin believed this church had its name in honor of the dense forest that protected the eastern part of the Kremlin until the 15th century.

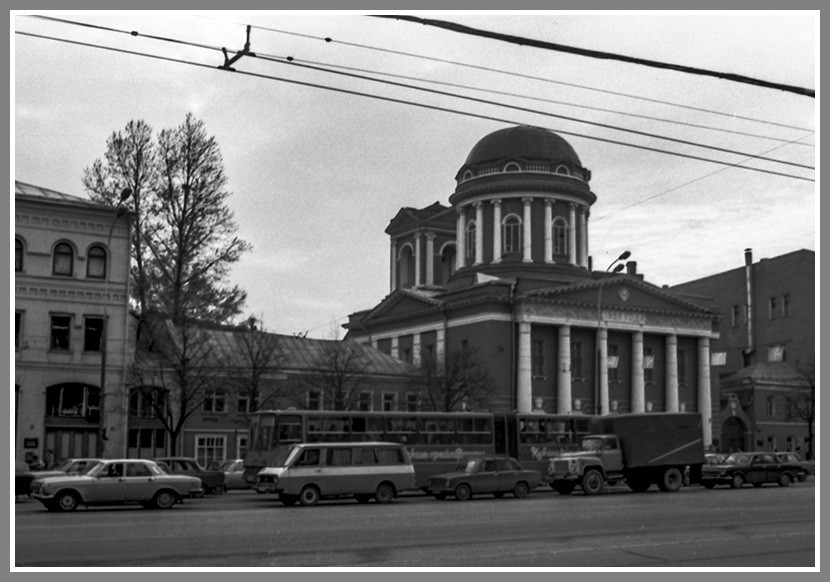

Church of St. John the Evangelist under the Elm Tree

home.nubo.ruIn these places, spruce and pine trees predominated, which were actively cut down and used by the city's population for construction. The city was expanding, and the forest was being cut down at its outskirts for building new houses. But these ‘outskirts’ were so close to the Kremlin that it’s now the very center of the city – even in the 17th century, places like Trubnaya Square (a 20 minute walk from the Kremlin) were still largely green, and until the early 19th century, bushes and trees grew right beside the Kremlin wall, in the now obsolete Aloisios’ Ravine, constructed in the 16th century under the supervision of Italian architect Aloisio the New. However, the city’s greenery wasn’t organized in a systematic way.

The Boulevard Ring

Tverskoy Boulevard in Moscow, early 19th century

Auguste-Jean-Baptiste-Antoine CadolleCatherine the Great, who wanted to update the old capital, ordered the construction of the Boulevard Ring. It took the place of the obsolete Belyi Gorod (‘White City’) fortification wall.

“Moscow is encircled by boulevards – they are not only an ornament, but also an important benefit,” Vladimir Odoevsky, a 19th century Russian journalist, wrote. “When foreigners, looking at the plan of Moscow, see this green ring, we are proud to explain to them that in winter and summer, both sick and healthy, and the elderly, and children can walk around the city, walk between the trees and not be afraid of being hit by a carriage.”

The Kremlin ravine, the 1800s

Public DomainAfter the fire of 1812, another green ring appeared – the Sadovoye (‘Garden’) ring, a wide street encircling the fast-growing center and covered in private houses’ gardens.

Greened by the Reds

Sokolniki Park, Moscow

Vasily Yegorov/TASSRapid urbanization starting after the 1917 revolution brought swarms of new inhabitants to Moscow, and the old city had to adjust to the needs of the industrial state. Unfortunately, with the 1930s Stalinist plan of Moscow reconstruction, many historical buildings were demolished, and main streets turned into highways.

Sadovaya-Kudrinskaya, Garden Ring, Moscow, 1928

Archive photoIn the 1930s, the Garden Ring was paved, trees at many squares and streets were cut down, there even were plans to destroy the Boulevard Ring, but fortunately they were not carried out. Georgy Popov (1906-1968), a Moscow Communist Party official, remembered that after WWII, in 1947, Stalin personally supervised the plans for re-greening the city center: “I remember how quickly we were deployed. We planted greenery on Dzerzhinsky Square (now Lubyanka Square), and in Okhotny Ryad, restored the garden on Sverdlov Square (now – Teatralnaya Square), and planted on Bolotnaya Square. Gorky Street was preplanted from Manezhnaya Square to Belorussky railway station. This was the first step in the greening of the central part of the city,” Popov wrote.

Sadovaya-Kudrinskaya, Garden Ring, Moscow, 1936

Archive photoIn 1951, the Moscow government chose from as many as 272 projects for re-greening Moscow. By 1961, forestry workers had planted over 500,000 trees and shrubs in the city. Small-leaved linden, blue spruce, fir, western thuja, irga, golden currant, barberry, and roses.

Gorky Park, Moscow, 1979

Boris Kavashkin/TASSThe 1950s-1960s also saw the reconstruction of Moscow’s biggest public parks. Gorky Park, transformed in the 1930s from Neskuchny (‘Merry’’) Garden, a 19th century public leisure space, has seen over 2,000 trees and 25,000 shrubs planted annually. The total space of the park expanded to 2.2 sq km, and the total length of the park’s alleys reached 30 km.

In the 20th century, more big parks were organized in Moscow: Sokolniki (5.16 sq km), Izmailovsky (16 sq km), Pokrovskoye-Streshnevo (2.22 sq km), Bitsevski Park (22 sq km), and, most importantly, Losiny Ostrov National Park (116 sq km), the largest urban park in Europe.

Felling a tree, planting two

Japanese garden in Main Botanical Garden in Moscow

Legion MediaCurrently, Moscow’s green affairs are under strict control from the city’s government. In 2010-2016, 432,000 trees and 3.5 million shrubs were planted, and since 2013, a government initiative called “A Million Trees” has been implemented, meant to plant vegetation inside the inner yards of apartment buildings, with the plants being chosen on a digital app platform by locals.

Cutting down a tree in Moscow (for example, during a house construction) is very difficult, and if you still have to resort to such a measure, then the developer is obliged to compensate for this by planting two trees. However, these rules do not yet apply to other Russian regions, even in close proximity to the city – for example, the Moscow Oblast’. In 2007-2012 in Khimki, a suburb in Moscow Oblast’, a part of forest containing ancient oaks was being cut down for a road construction project. The project was eventually implemented, and a section of toll road was organized, causing air pollution near the highway, and in addition, noise pollution in the forest.

According to Moscow government’s official portal, by the end of the year, over 5,000 trees and 136,000 shrubs will be planted in Moscow, so the city is not going to lose its status as the greenest capital of the world any time soon. However, the indexes of the air pollution in Moscow are still unfortunately high – the city is still Russia’s largest trade and industrial center. The World Air Quality index places Moscow in 27th place in the air pollution ranking.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox