There are numerous interesting facts about the Nanai people. For example, their other name was ‘Fishskin’, because they wore clothing made out of fish skins. These days, a traditional Nanai costume like that would cost about $2,500-$4,000. Here is another interesting fact: when a Nanai person dies, a special ceremonial bib is made for them embroidered with a pattern in the form of intestines, while a small wooden doll was made to honor them, which was “fed” for another year after the person’s death. Then, there are the Nanai surnames. To this day, there are only 30 of them.

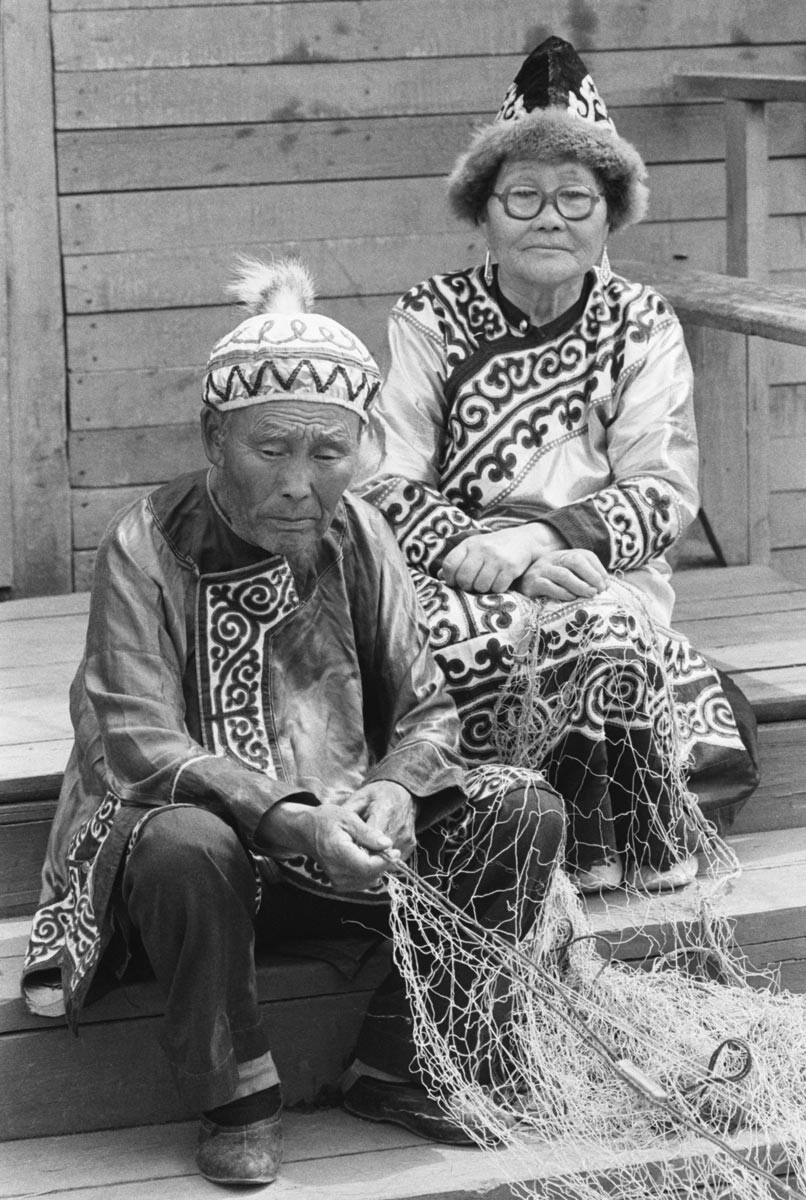

The Beldy family from the village of Daerga. Nanaysky District, 1987

Dmitry Korobeinikov/SputnikThe Nanai, like representatives of many other indigenous peoples of Russia, have now become almost fully assimilated with Russians. Few of them know, let alone use, the Nanai language in everyday life. And, yet, the Nanai continue to be the indigenous inhabitants of the Far East, who lived on this land before it was discovered by the Chinese and then the Russians.

Researchers are still divided as to where the Nanai first came from. Some believe that the ancestors of the Nanai originally lived in Manchuria (present-day northeast China) and then moved to the lower Amur and the valley of the Ussuri River. Others, like the ethnographer Lev Sternberg, believe that the Nanai people emerged through a mixture of different tribes. This theory was confirmed by a genetic analysis of the Nanai people. It turned out that different Nanai clans are strikingly different from each other in their ethnic composition: some can be traced to China, while others - to the Turks, Mongols or the Tungus.

Although the first mention of a Nanai settlement in Russia dates back to the 17th century, these people had lived on this land for centuries. Literally, “nanai” means “a person of the earth”. At the time of Russian colonization, they were called “outlanders” (back then, the word meant a representative of any ethnic group other than Russian) and now they are officially called “a small-numbered people”.

According to the 2010 census, there are 11,671 Nanais living in Russia. Another 4,600 Nanais ended up in China after the 1860 Treaty of Beijing, which drew the state border along the Amur and Ussuri rivers and divided the area populated by them between Russia and China.

When the Russians came to the Far East, the indigenous peoples were faced with a choice: either accept Russian rule or leave. The Nanai chose to remain on their historical lands. These days, more than 92 percent of Russia’s Nanai population live in Khabarovsk Territory: in the city of Khabarovsk and in villages on both banks of the Amur and the Ussuri, which are about a four-hour journey from Khabarovsk.

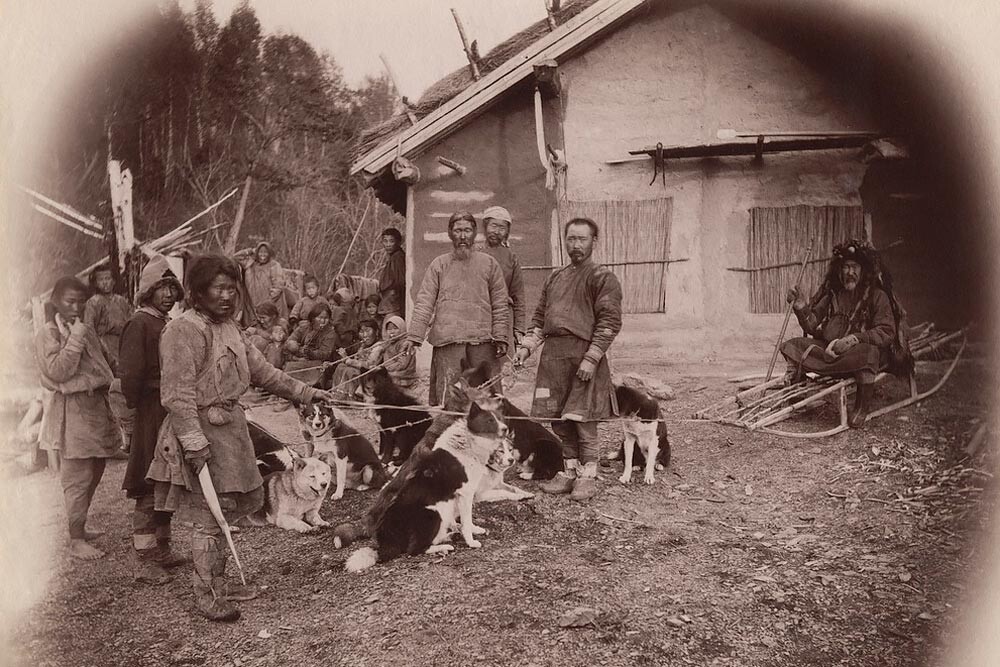

Shaman's ceremonial ride on dogs, 1900s

V. Soldatov / Union of Russian Photographers / Russia in photoThe Nanai were presented with another ultimatum when, in the second half of the 19th century, they were converted from paganism into the Russian Orthodox Church. In the Nanai traditional faith, nature had a soul, which could be contacted through shamans and with the help of dogs. The Nanai believed that dogs were guides and helpers for shamans to find “stolen” human souls.

The souls of the dead were taken care of differently. A deceased person had a burial bib prepared for them embroidered with a pattern in the form of intestines so that the soul of the departed could breathe and eat. In the coffin, a stone was placed at the corpse's feet, at their heels, so that the deceased would not rise to the souls of the living. For the same purpose, the deceased was taken out of the house through a broken opening or a window, but never through the door, so that they would not find their way back home. The Nanai believed that the soul of the deceased “lived” for a year after their death in a small wooden doll called ‘pane’. Every day, the doll was fed and, a year later, the shaman would send the dead person’s soul to the afterlife. Until the end of the 19th century, the Nanai buried their dead in “houses” that stood above ground. It was only in more recent history that they began to bury their dead in the ground.

The traditional Nanai dress consists of a wraparound robe and pants, which are embroidered with patterns that always mean something: protection from evil spirits, wish for good health, good catch, etc. “Can you see this bib? I made it myself. It was meant to scare away evil spirits. The more metal decorations on it and the louder they jingle, the better. Previously these bibs were worn under clothes, but now it is customary to wear them over one’s clothes,” says Elena from the village of Sikachi-Alyan.

Many modern Nanais practise two religions at once. They go to church, but, at the same time, they make offerings to the spirits of the river “for good luck” and, just in case, leave coins at the Savan ritual sculpture.

When they were issued with Soviet passports, the Nanai had to be given last names - for the first time in their history. Until 1974, the Nanai people never had last names. When the requirement for all Soviet citizens (with the exception of military personnel) to have a passport was passed half a century after the USSR was formed, the Nanai came up with Nanai last names for themselves on the basis of some of the most obvious logic. For surnames, they took the names of the clans they belonged to. Thus, they ended with a total of 30 Nanai clan surnames: ‘Possar’, ‘Aimka’, ‘Digor’, ‘Nuer’, ‘Yukomzan’, etc.

The largest clan is ‘Beldy’. Its most famous representative is the singer Kola Beldy (1929 - 1993). The song ‘I Will Take You to the Tundra’ won him the second prize in the main competition at the Sopot International Song Festival (Poland), after which he toured for many years, visiting 46 countries. His lyrics describe life in the tundra and reindeer herding, although the Nanai have never lived in the tundra or bred deer.

Hunter on skis on ice floe, with spear and rifle

Library of Congress / Public DomainThe Nanai are born fishermen. There are about 140 species of fish present in the Amur. Even five months of the Nanai calendar are named after fish.

The dwellings and everyday life of modern Nanai differ very little from typically Russian ones. Internet, household appliances, cars, modern motors for boats, portable power units - all these are used by the Nanai, even in remote villages. Although the majority of Nanai, especially the young and able-bodied, live not in villages, but in nearby cities, where ethnic Nanai are a minority.

“It’s good to be a Nanai in a Nanai village and go to a Nanai school, but few manage to do that. But when you are the only Nanai in a school, everyone considers it their duty to tease you about it. There was even an insult: ‘What are you, a Nanai?’,” says Leonid Sungorkin, president of the Association for the Protection of Culture, Rights and Freedoms of the Indigenous Peoples of the Amur Region.

July 11, 1990. Nanai couple Ivan Torokovich and Maria Vasilyevna Beldy.

Sayapin Vladimir/TASS/TASSEven fishing - the traditional livelihood of the Nanai people and their main source of food - is subject to modern realities. In Russia, the law determines which indigenous peoples can catch fish and how much. For the Nanai, the quota is 50 kilograms of fish per person per year, or 100 kilograms, if the family has three or more children in it. This is the most “high-profile” benefit, which, according to the Nanai, does not really work in practice. Nanai living in cities cannot afford it: they do not have a boat, nets, they are elderly, or they have a job and have no time to fish. At the same time, there is no financial compensation envisaged for those who do not use up their fishing quota.

Teacher Anna Denisovna Onenko explains the basics of applied national art and handicraft techniques at school.

Shlyakhov A./TASS“Also, the Nanai people are entitled to timber for building a house. But, this is also a complicated story, because they are allocated a bit of forest somewhere far away and are expected to clear the taiga, cut down the trees, clean, prepare, transport all that timber and only then build a house. This is unrealistic,” Sungorkin says.

Still, some Nanai have managed to benefit from their origin. In the 2010s, they began to develop ethno-tourism, having turned the Nanai culture into a tourist attraction.

“Trips to Nanai settlements are becoming more and more popular. We have been offering them since 2016 and the demand has not dropped. Moreover, people travel from everywhere - from our region and from neighboring regions and even from Moscow [which is 8,240 km from Khabarovsk] and other western parts of Russia,” says Olga Pomitun, from the Khabarovsk-based travel agency Voyage.

Odo Beldy, 92 years old, the oldest resident of the village of Naikhin, 1987

Dmitry Korobeinikov/SputnikOn a visit to a Nanai village, tourists can try their hand at archery, learn how to cook traditional Nanai dishes, taste them, play Nanai games and buy Nanai handicrafts.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox