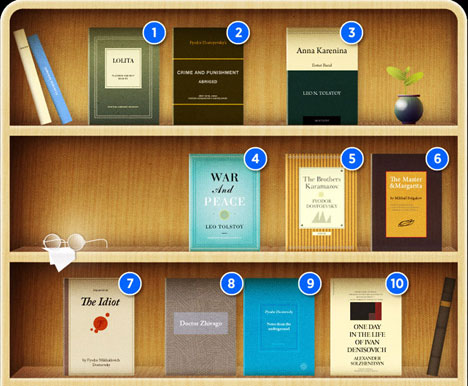

The Top 20: Readers vote for the best in Russian fiction

Click here to enlarge the picture. Drawing by Anton Panin

The books are in the order of the number of votes they received. So grab your Ipad, your Kindle, or run to the last independent bookstore in your area—and support it!. Then let us know what Russian stories transported you this summer to new and distant shores. Happy Reading!

1) “Lolita” (1955-58) “Lolita” is without doubt Vladimir Nabokov’s most provocative work. The story of a relationship between a mature man and a 12-year-old girl both gripped and scandalized readers. Stanley Kubrick directed the film in 1962 from a script written by Nabokov himself. The work ranks fourth in the Modern Library top 100 English-language works.

2) “Crime and Punishment” (1866) Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote this urban novel, published in 1866, about the criminal ambitions and delusions of an impoverished student. The author himself serialized the work to pay back a gambling debt. One of the Russian novels most frequently adapted to film (8 films have been made), it has provided the basis for a multitude of stage plays.

3) “Anna Karenina” (1873-77) The novel’s famous opening sentence, “All happy families are alike, but an unhappy family is unhappy after its own fashion,” (Penguin Classics translation) has become known as “the Anna Karenina principle.” Readers follow the emotional decline and eventual tragedy that befalls Anna, although a few resent what they view as the melodramatic plot. The novel has been adapted to the screen more than 20 times all over the world. The upcoming British version, starring Keira Knightley and Jude Law, will be released in September.

4) “War and Peace” (1863-69) This four-volume epic novel was conceived as a story about the Decembrists, the 19th century opposition movement spawned within the aristocracy. Yet, to trace the sources of the Decembrist movement, Tolstoy also delved into the history of the 1812 war against Napoleon. The author rewrote the novel in longhand about seven times and some episodes more than twenty times. Each time he edited it, he found ideological and artistic flaws in it, he later said.

5) “The Brothers Karamazov” (1880) This is known as Dostoyevsky’s most philosophical and intellectually challenging work. The writer died before completing it. The existing novel is only the first part of what was to be “The Story of a Great Sinner.” By the end of the series, Alexei Karamazov was to become a revolutionary. The writer did not live to see the first attempt on the life of Tsar Alexander II, otherwise that event might have led him, a monarchist, to give the novel a different twist.

6) “The Master and Margarita” (1929-40) Unofficially, Russian critics refer to Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel, “The Master and Margarita,” as the most intriguing of all the 20th-century novels. The plot consists of “a novel within a novel,” stories from different cultures and epochs and unorthodox portrayals of the Devil and Jesus—all of which are striking and highly unusual for Russian literature. The Soviet authorities could not accept a novel that touched on religious matters and, for a long time, it was available only through samizdat (self-publishing), while the first posthumous publication in Russian was heavily censored.

7) “The Idiot” (1868) Dostoyevsky’s novel, “The Idiot” refers to an unduly humble and timid person; in this case, Prince Myshkin, is an embodiment of Christian morality, but after years in a sanatorium for seizures, he becomes entangled with two women, who appear to be moral opposites. The Prince is a classic holy fool, too naïve and too trusting for the menaces of the real world.

8) “Doctor Zhivago” (1945-55) “Doctor Zhivago” is at once a novel and a collection of poems by the doctor and poet Yuri Zhivago. The Soviet Communist Party felt that Boris Pasternak gave an ambiguous interpretation of the Bolshevik Revolution and other “glorious” pages in the history of Communism. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1958 but the then Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was enraged by the high appraisal of an anti-Soviet novel. Pasternak was forced to reject the prize. Doctor Zhivago was published finally in the Soviet Union toward the end of perestroika (1988), when the writer’s son received his great father’s Nobel diploma.

9) “Notes from Underground” (1864) This short satirical work by Fyodor Dostoyevsky reflects his artistic and ideological principles. A deeply disturbed man narrates his own story as he finds himself on the verge of insanity. He is one of the first “anti-heroes” in fiction, and is the precursor of the tragic characters in “Crime and Punishment,” “The Idiot,” “Demons” and “The Brothers Karamazov.” The character is one of the last members of the Russian intelligentsia to challenge the rest of the world.

10) “One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” (1959) A brutal rendering of the Soviet labor camps, the work shook the Soviet Union and the whole world with its portrayal of the horrors of daily life in a GULAG camp. The poet Anna Akhmatova made this comment on One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich: “This is a story everyone must read and learn by heart – every citizen of the Soviet Union.” Miraculously, Nikita Khrushchev approved of the story and it was spared the fate of underground literature, unlike other truthful accounts of labor camps.

Yet Solzhenitsyn’s other stories of the GULAG were less favorably received in the U.S.S.R. and the writer was expelled from the country after being awarded the Nobel Prize.

{***}

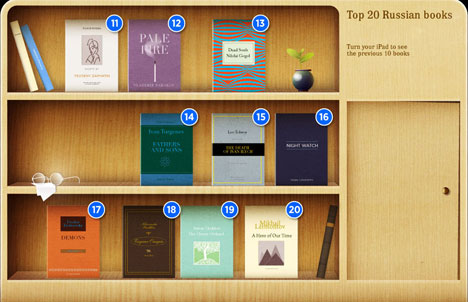

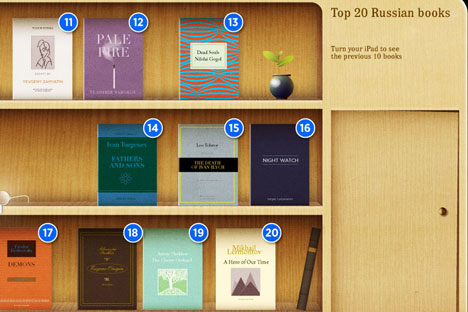

Click here to enlarge the picture. Drawing by Anton Panin

11) “We” (1920) American and French readers bought the novel before Yevgeny Zamyatin’s fellow-countrymen. The novel was first published in New York. In the USSR, it was published during the perestroika years, like many other “undesirable” works. This 1920 anti-utopia had influenced George Orwell’s “1984,” Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451” and Aldous Huxley’s “The Brave New World.” Yevgeny Zamyatin was inspired by the science fiction of Herbert Wells.

12) “Pale Fire” (1962) Vladimir Nabokov conceived of this novel before he moved to the United States, but remarkably, he wrote as an émigré in English. It is a poem with a non-linear structure and a host of literary allusions. Even the title is borrowed from Shakespeare’s tragedy “Timon of Athens”: “The moon’s an arrant thief,/And her pale fire she snatches from the sun.”

13) “Dead Souls” (1842) Nikolai Gogol’s“Dead Souls” is as funny as it is great. The brilliant and biting plot involves the character Chichikov, a man with modest means who makes an industrious trade of dead serfs by keeping them alive on paper. Though written in prose, Gogol thought of the comic satire as a poem. He planned to write three volumes corresponding, respectively, to Dante’s “Paradise,” “Purgatory” and “Inferno,” in which the heroes were to traverse a path of transformation from soulless and spiritually bereft in the first volume to enlightened and high-minded in the third. But the writer thought even the second volume to be a failure and burned the unfinished version.

Even so, the rough drafts survived and were published after the writer’s death. Incidentally, the unusual plot was suggested to Gogol by the poet Alexander Pushkin.

Related:

The seven jenres of Russian literary giants

14) “Fathers and Sons” (1861) Ivan Turgenev to this day offers an insightful portrayal of intergenerational conflict with “Fathers and Sons.” The main character, Yevgeny Bazarov, is a representative of “superfluous people” in literature. He puts rationality above all else and denies all feelings, which leads to his undoing. Yet exalted 19th century intellectuals and revolutionaries admired Bazarov for his Nihilism.

15) “The Death of Ivan Ilych” (1882-86) One of the latest works by Leo Tolstoy met with a cool reaction from readers and critics. The overly naturalistic and detailed description of the illness and death of a man seemed, to his acolytes, un-Tolstoyan. Eventually, the hero finds bliss in death, which led Vladimir Nabokov to see echoes of Buddhism in it.

16) “Night Watch” (1998) “Night Watch” is the only contemporary work from the past decade to make the Top 20 list. Sergey Lukyanenko’s imagination created a whole world of Others, powerful magicians who live among people, creating a spell-binding tale of magic in Moscow. While the Light and Dark magicians settle accounts in the manner of special services using fireballs and chants instead of machine guns, the heroes constantly face the dilemma of whether it is pardonable to use “dark” methods to achieve “good” ends. The first two of the “watch” novels were made into films by Timur Bekmambetov.

17) “Demons” (1872) Dostoyevsky’s sixth novel is devoted to political matters and depicts radical terrorists. In Russian literature, the revolution is generally depicted as an irrepressible storm. Demons are the embodiment of the dark forces that drive the revolution and possess the heroes, making them violate the laws of humanity and morality.

18) “Eugene Onegin” (1823-31) This is a novel in verse, a genre invented by poet Alexander Pushkin to shake off the fetters of the novel and acquire poetic freedom. Foreign readers are captivated by the depiction of a bored Russian dandy. Initially, Pushkin admitted that he did not know what the end would be. The famous 19th century critic Vissarion Belinsky described Eugene Onegin as “an encyclopedia of Russian life.”

19) “The Cherry Orchard” (1903) Anton Chekhov subtitled this work a “comedy” but there is little mirth in it. The break-up of a family is portrayed against the backdrop of the country’s transformation and emergence of new attitudes at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. This is Chekhov’s last play, written shortly before the 1905 revolution. It is hard to think of another play that has been staged so often within Russia and elsewhere.

20) “A Hero of Our Time” (1838-40) Mikhail Lermontov’s work further explores the anti-hero; thischaracter travels through the Caucasus and kidnaps a beautiful woman—among his many exploits. The narrator is first the author, then his fellow traveler, and finally the main hero.

Lermontov gradually reveals the main character, Grigory Pechorin, as a world-weary young man who is incapable of strong feelings and brings nothing but suffering to the people around him. He belongs to the same category as the anti-heroes of Pushkin’s “Eugene Onegin” and Turgenev’s “Fathers and Sons.” Readers continue to be drawn to these characters of limited feeling and self- destructive tendencies. The Russian anti-hero takes us on an emotionally charged journey. But in the end, they often help us feel better about ourselves!

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox