From shaving to potatoes: 5 things that Peter the Great brought to Russia

Portrait of Peter I of Russia (1672-1725)

Maria Giovanna ClementiPeter I, who would subsequently be called "the Great" after his death in 1725, was one of Russia's most energetic and active rulers. Throughout his life he tried his hand at various crafts and skills - learning engineering, architecture, and shipbuilding. At the same time, he ruled his country with an iron fist.

It's little wonder that Peter personally, though incognito, participated in Russia's Great Embassy to Europe (1697-1698), eager not only to strengthen the alliance with certain countries, but also to study European life and learn from it. Soon after his return, Russian civilization began to change rapidly as the inspired young tsar spared no effort to modernize and reform the existing order. So, what exactly did he bring to Russia from Amsterdam, Vienna and other European cities?

1. European chic

Peter I in a foreign dress, Stavropol Art Museum Russia. / Global Look Press

Peter I in a foreign dress, Stavropol Art Museum Russia. / Global Look Press

“You have no second chance to give a first impression,” probably thought Peter while looking at Russia's aristocrats (boyars). Long-bearded and dressed in massive kaftans, they looked nothing like the sophisticated European noblemen who had powdered wigs and clean-shaven faces.

So, Peter decided once and for all that every nobleman must be clean-shaven and wear European clothes. Though he admired Westerns ways, Peter remained the ultimate autocrat. His reforms were easy to implement. During assemblies and court balls he personally cut off beards and tore apart traditional bulky clothing. The boyars, who remembered that their monarch was also capable of cutting off heads such as during a failed palace coup in 1698, feared Peter so much that they quickly bid farewell to their beards and changed their looks.

2. Modern calendar

Until 1700 Russia lived according to the ancient Hebrew calendar from the Bible that came to Moscow via Byzantium and which commenced from the moment of the world’s creation (believed to be in the year 5508 BC). After his travels, Peter understood it was absurd that all of Europe lived in the year 1700, while Russia lived in 7208.

Following his return to Russia Peter literally rewrote history, proclaiming December 19, 7208 as January 1, 1700. At the same time he changed the day when Russians celebrated the New Year - from September 1 to January 1. Traditional society, especially Old-Believers, already considered Peter the Antichrist, and now they were mad as hell. But again, one can't so easily protest the tsar’s decision.

3. Printing press

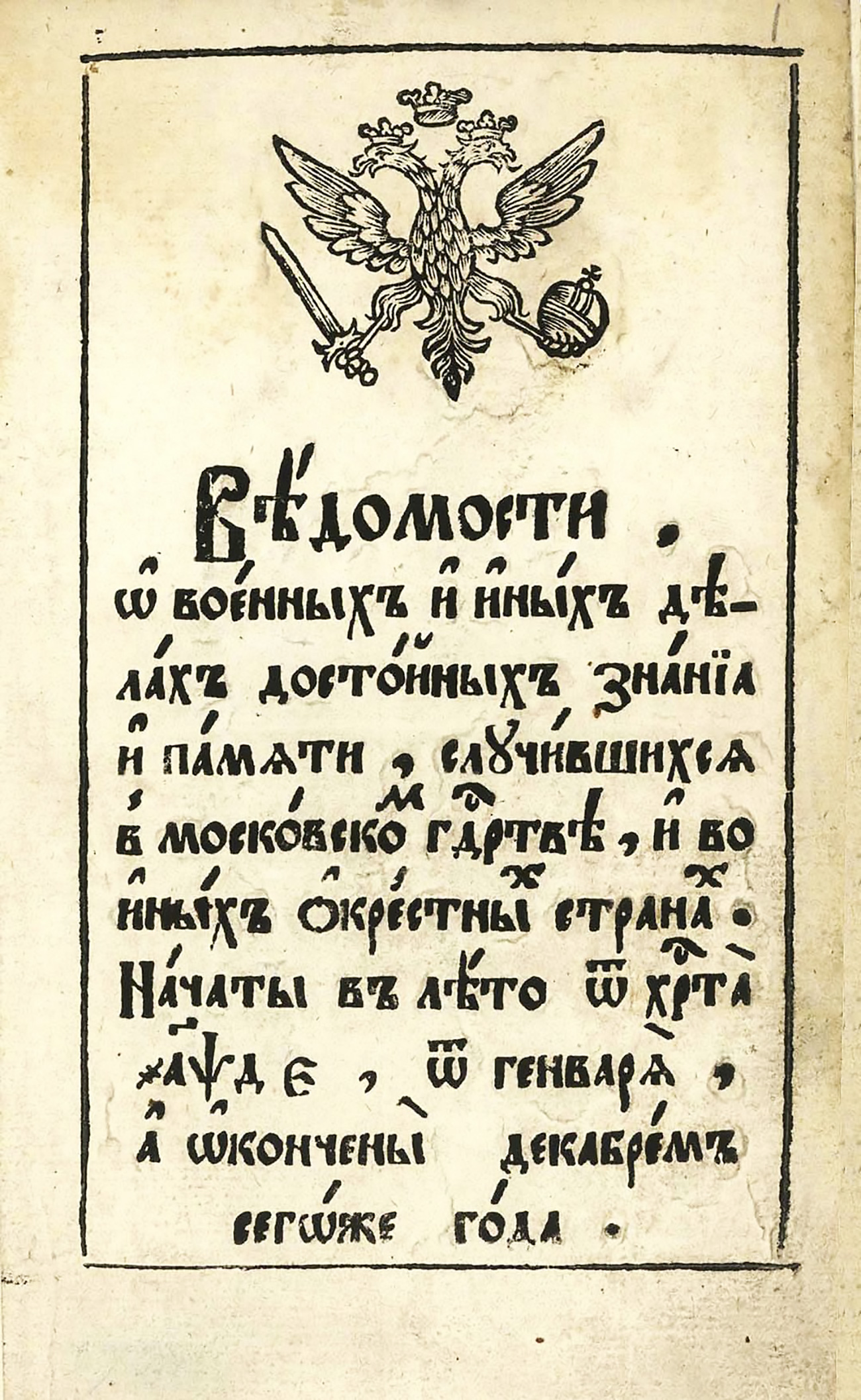

Vedomosti newspaper. / Archive photo

Vedomosti newspaper. / Archive photo

Under Peter’s rule the first newspaper was printed in Russia on January 13, 1703. Impressed by the rudimentary Dutch media industry, the Czar was sure that his people also deserved to know something about the world around them. The first paper was called Vedomosti, and contained 2 to 7 pages, and was basically a collection of facts from different spheres of life, with no headings and no structure. In the same paragraph it could tell about the harvest in a remote city and about a European war.

Nevertheless, the audience was not demanding when the first edition of Vedomosti was published. In fact, it was not demanding at all since the vast majority of Russia’s early 18th century population was illiterate. Still, the fact remains: Peter the Great was the first Russian media mogul.

4. Census

Peter was very active in domestic and foreign affairs, for instance, continuing the never-ending wars with Sweden and Turkey and finishing construction of his new capital, the magnificent St. Petersburg. But this meant that the state was in constant need of money. To address this issue, the tsar decided to reform the fiscal system.

Before his reign, peasants paid a sum of money as a single household and often tried to fool the state by combining several households into one big estate. The fiscal reform called for each male peasant to pay 70 kopeks, which left no way to deceive the government. In order to know the approximate population of Russia, Peter held his country's first census. According to historians, there were approximately 12 million people living in Russia in 1715.

5. Useful food products

A reproduction of the painting "Potato Picking" by Arkady Plastov. From the collection of the State Russian Museum. / RIA Novosti

A reproduction of the painting "Potato Picking" by Arkady Plastov. From the collection of the State Russian Museum. / RIA Novosti

In Russia today it's common to see people frying potatoes with sunflower oil. Probably not many Russians, however, know that we do this today because Peter the Great brought home from Holland both potatoes and sunflowers, (they originally came to Europe from the Americas in the 16th century). The tsar foresaw that Russians could make good use of these, but people resisted at first.

While peasants rather quickly understood what to do with sunflowers, the potato proved a challenge. They were strictly demanded to grow the tuber, but received no instruction how to cook and eat it. Instead of consuming potatoes, which they should have done, they tried to eat the inedible potato leaves and often poisoned themselves. In fact, peasants used to call it the “Devil’s apple.” But after a while everyone made peace with the tuber and by the late 19th century it became “the second bread” for Russians.

Read more:

Where to find the Amber Room, a cultural treasure stolen by the Nazis

'Don’t eat like a pig' and other rules of etiquette from Peter the Great

True or false: How much do you know about Russia’s first emperor?

The first Romanov political exile: How Peter the Great's son fled Russia

What was so ‘Great’ about Catherine?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox