9 Russian dining rules from the early 19th century

"At the Tea Table", Alexey Voloskov, 1851

Public domain“It was possible to arrive for lunch and sit at the table without an invitation,” wrote French philosopher Hippolyte Auger about Russian hospitality. “The hosts gave their guests full freedom, in turn doing what they pleased, without paying attention to the visitors.” So, what then was the hospitality of Russian landowners known for?

1. Large family dinners and a foreign chef

The early 19th century was a time of landowners and peasants. While the life of the latter was very modest, landowners held large and lavish family dinners with the entire household attending. The table was set by servants, who were usually serfs. They also prepared the meals. Wealthy landowners had foreign chefs, which was something to brag about to one’s neighbors.

2. Strict lunch time

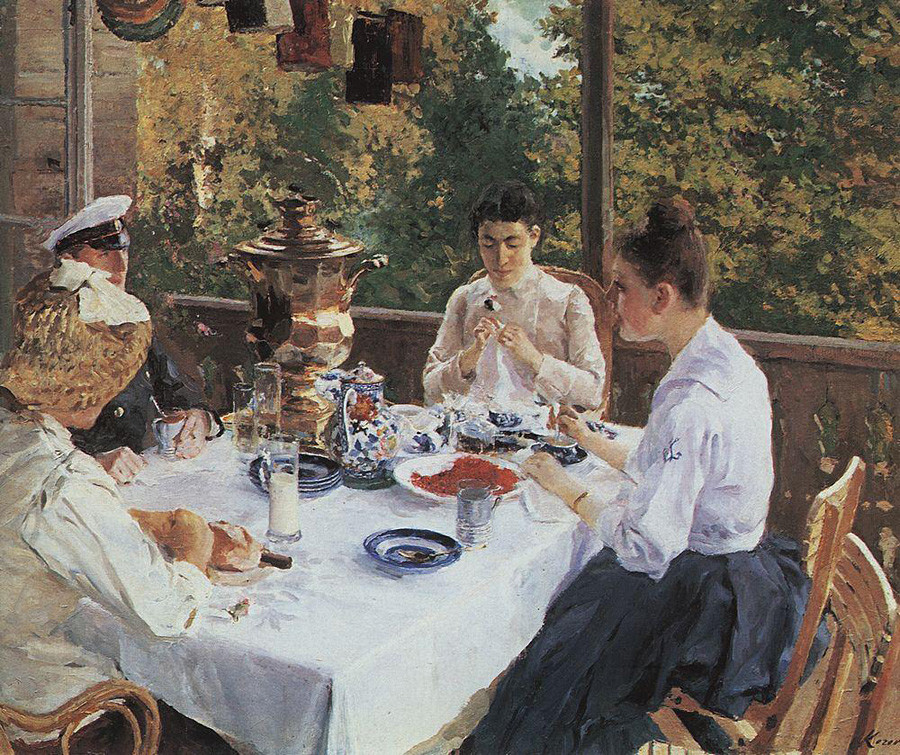

"At the Tea Table", Konstantin Korovin, 1888

Public domainLunch was usually eaten at noon or at one o’clock. There is a famous story of how Emperor Paul I heard that Countess Golovina took her lunch at three o’clock, and so he sent a police officer ordering her to always have lunch at one o’clock, which was when the Emperor always ate.

“In the years right before the war with Napoleon,” remembers D. N. Begichev, “most people lunched at one o’clock, some who were more important at two and only the fashionable ones lunched a bit later, but not after three.”

3. Business lunches

During lunch and dinner people not only ate but sometimes also settled business affairs. Guests came to visit the host, and during the meal the landowner would talk with his administrator about the estate.

4. Place at the table

Seating had great importance. At the head of the table sat the landowner, to his right sat his spouse, and to his left the most esteemed guest. The further a person sat from the landowner, the lower was his social position, or the less significant his relation to the host. The servants followed this seating arrangement when they served meals.

"Hiring a servant", Vladimir Makovsky, 1891

Tretyakov Gallery“Sometimes a servant did not know a visitor’s rank and would look at his master anxiously. One glance was enough to put him on the right path,” wrote an anonymous author to his friend in Germany.

Not surprisingly, superstitious hosts made sure that the table never had 13 people.

5. Tableware

Tableware depended on the host’s prosperity. If rich, dishes were made of silver. For example, in 1774 Catherine the Great gifted her favorite, Count Orlov, a silver dining service weighing more than two tons. The napkins that were used at the table usually had the host’s initials embroidered in the middle.

6. Serving the meal

In accordance with Russian tradition, courses were served one by one, not all at once. This mid 19th century tradition was borrowed by the French, and then by other Europeans. Wine was also served after each course, except “common wine in a carafe that is drunk with water” (from Dining Etiquette in the 19th Century, E. V. Lavrentieva).

7. Toasts after the third course

The most important guest pronounced the first toast, which was said not at the beginning of the meal, but usually after the third course. If the emperor was present at the table, he made a toast to the health of the hostess.

8. Conversation

"Evening society", Vladimir Makovsky, 1875

SputnikYou could not discuss illnesses, servants or romantic relationships at the table. Silence was considered bad manners, or a sign of a bad mood. Good manners were expressed by engaging in light conversation. If two neighbors at a table were speaking, they had to speak rather loudly so that the other guests could hear.

9. Dessert to conclude

Lunch began with the sign of the cross, and dessert concluded it. Fruits, candies or ice cream were served for dessert. At the end of dessert, cups were passed out so that guests could rinse their mouths. The custom of rinsing one’s mouth was fashionable at the end of the 18th century. Guests would also make the sign of the cross as they got up. Etiquette required that guests get up only after the most honorable guest had done so. A return visit was made no sooner than three days, and no later than seven days after the lunch.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox