Evolution of biological protection suits from the 17th century to today (PHOTOS)

Clothing offering protection from harmful environments is not a new invention. It was clear even during the first epidemics of plague that it was best to maintain a safe distance from anyone with the infection, and if distancing was impossible by virtue of professional necessity - in the case of doctors, for instance - physical contact had to be kept to a minimum. This awareness evolved through trial and error, of course, so that the “plague doctor’s” outfit (long leather overcoat, gloves, and a mask with a long “beak”) only appeared in the 17th century. Today, it is constantly being perfected and developed, having become the prototype for the special garments used for work in hazardous conditions.

Anti-plague suits

Deadly epidemics raged in many countries, including Russia, in the early 20th century: tuberculosis, typhoid, smallpox and flare-ups of plague. It had already been discovered by that date, that many viruses were transmitted either through airborne droplets or via mucus, and so, anyone working in infected areas had to wear special clothing.

During the last big epidemic of plague in Manchuria (1910-1911), the Russian Empire set up cordons sanitaires on the Chinese Eastern Railway to prevent its spread into Europe. Entry from Manchuria was prohibited, and residents of China could only board a train after spending five days in observation.

Desinfectors in Habrin.

Martinevsky I.L., Mollyare G.G., 1971All medical workers and disinfection teams had to wear special costumes with hoods, masks and gloves.

After every shift, all the outer garments were rinsed down in the open air with a solution of mercuric chloride or carbolic acid, and then cleaned at a specially designated laundry. Footwear was disinfected with the aid of a pressure pump. Historians say there were sporadic cases of the disinfection procedures not being observed, and these ceased after a number of sanitary workers became infected and died.

This kind of outfit is still called an anti-plague suit, even though doctors and scientists wear them when working with other agents of disease, such as smallpox, bird flu and coronavirus.

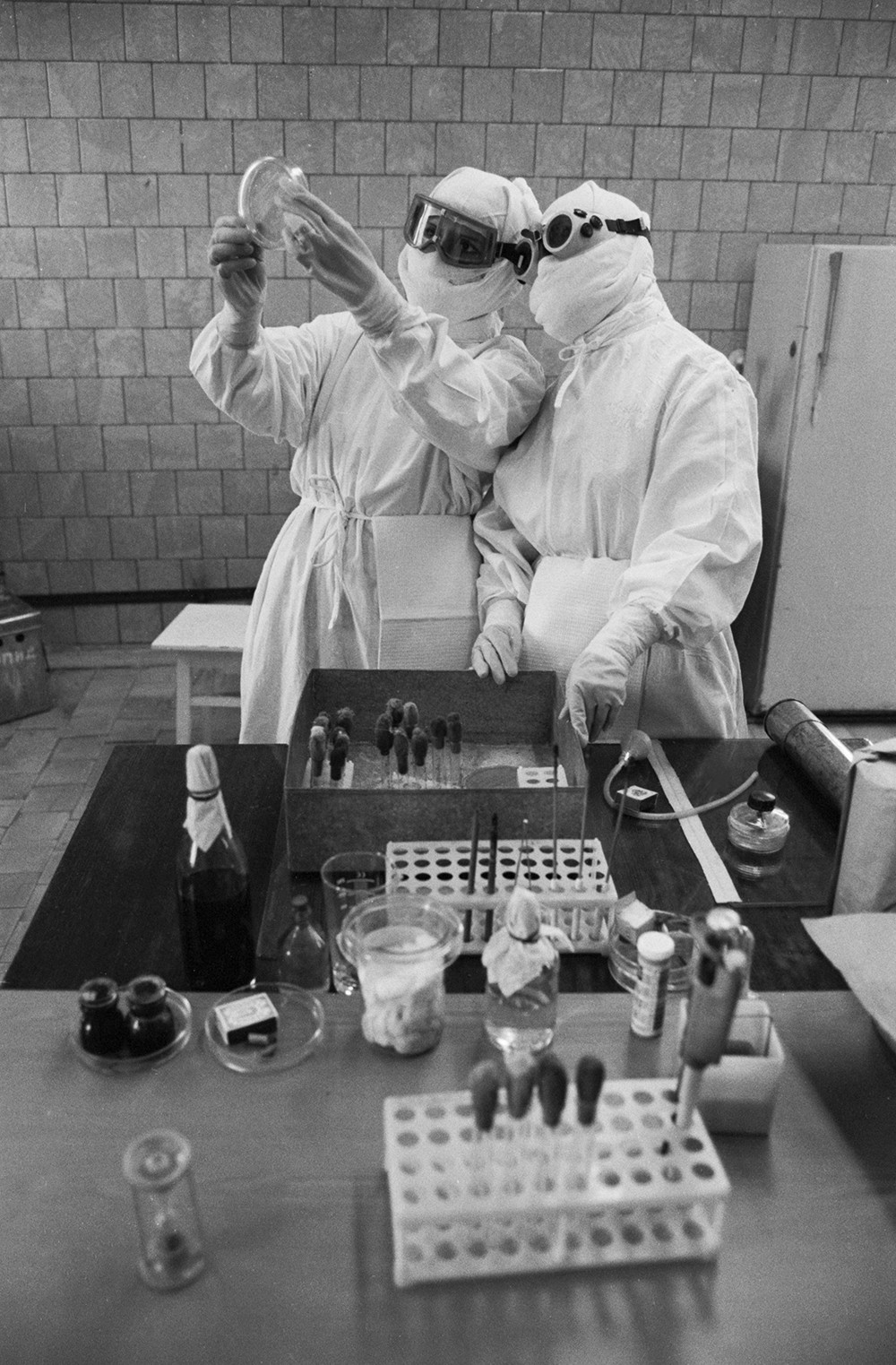

Anti-plague institut in Volgograd.

Eduard Kotlyakov/TASSThe suits consist of a whole-body garment (officially termed “pyjamas”), a hood, a gown, protective eyewear, a face mask, rubber gloves and boots. The whole outfit can also include breathing equipment.

Under Russian legislation, costumes of this kind must be available, not just in hospitals and outpatient clinics, but also emergency vehicles manned by anti-infection teams. Ambulance crews normally use the disposable version.

Anti-plague suit, the Moscow Region.

Valery Melnikov/SputnikDisposable suits are also currently worn when dealing with passengers arriving from abroad who are suspected of having coronavirus. They are much cheaper and are made of simpler materials: For instance, instead of boots they have laced shoe covers and, instead of a protective gown, there is a one-piece overall with arm protectors or an apron. The materials are also different: The disposable one is made of synthetic materials like polyester, while the reusable version is of heavy-duty cotton or viscose with a water-repellent surface.

At the Sheremetyevo airport.

SputnikAccording to sanitary regulations, the disposable suit has to be soaked in disinfectant and destroyed after a shift, while the multi-use one can be worn again after suitable cleaning. Whatever the type, the suits are made with a minimum of seams in order to stop viruses penetrating the wearer’s clothing.

Biological and chemical protection suits

Members of the military who work in contagion zones don’t wear anti-plague suits, but proper anti-exposure suits.

Something similar was also developed in the early 20th century, however not to counter a bacteriological threat, but a chemical one - the use of mustard gas in World War I. At the end of 1916, Russia had special chemical teams in the army, and full-fledged chemical troops were set up in 1918 after the Revolution (today they are called the radiation, chemical and biological protection troops). By the start of World War II, the USSR had suits made of special rubberized fabric that afforded protection from mustard gas fumes.

An anti-chemical weapon exercise in the 1930s.

MAMM/MDFAn all-service protective suit designed to be used not just for chemical threats but also biological ones was adopted by the Soviet army in the 1960s.

Measuring radiation in Chernobyl, 1986.

MAMM/MDFIn addition to a whole-body garment, hood, gloves and face mask (or respirator), the kit includes over-boots, an air filtration unit and spare filters.

Decontamination in Bergamo.

Russian Defense Ministry/TASSIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox