“First day underwater. A rock, overgrown with an underwater thicket, is visible nearby. It’s teeming with life. Crab Mitka settled in a crevice. Sometimes, he leaves his shelter, crawls the rock phlegmatically, while always chewing on something in the meantime. Night fell. Lightning blazes in one or the other porthole – these are simple microorganisms glowing,” amateur aquanaut Alexander Haes, the inhabitant of the first underwater house in the USSR, wrote in August 1966.

The 1960s in the Soviet Union were marked by a thirst for exploration of not only space, but the sea depths, as well. Donetsk divers were the pioneers in this, whose enthusiasm was spurred by the news of the successful experiments of famous French explorer Jacques-Yves Cousteau. In 1962, he lowered the world-first underwater house ‘Conshelf I’ to the seafloor and, in 1963, he “built” a whole village on the floor of the Red Sea.

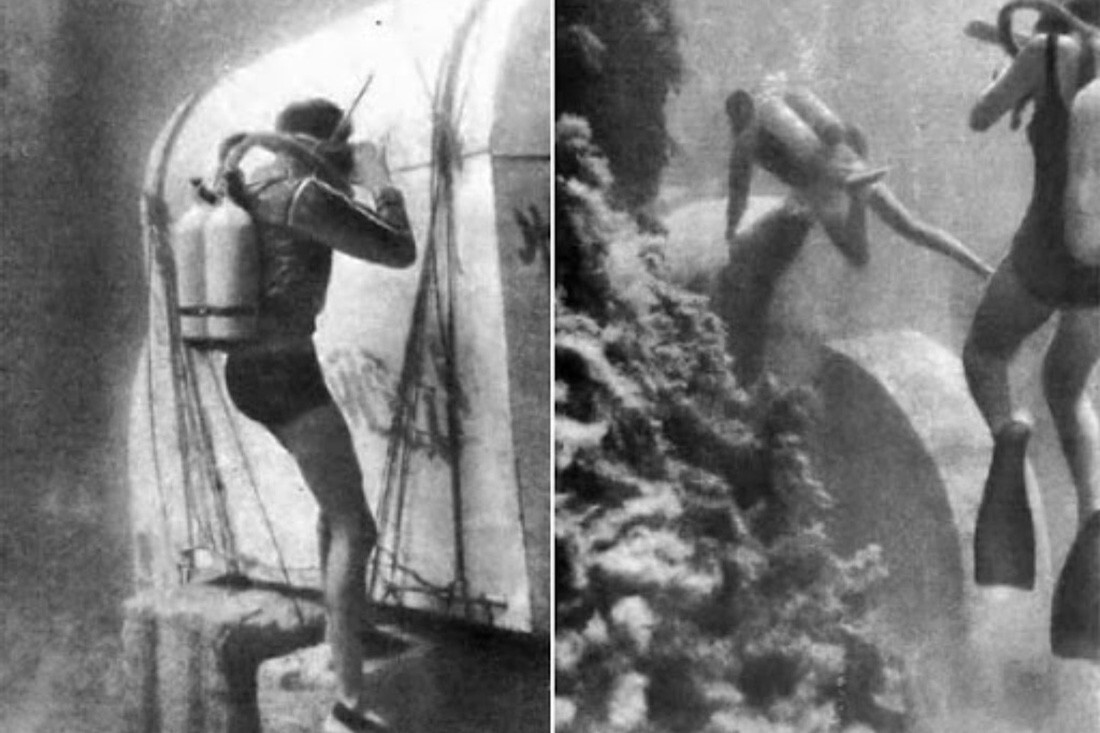

‘Ichthyander-66’

Archive photoWhile, in the West, professionals dealt with the construction and testing of underwater homes, in the USSR, the first attempts were undertaken by amateurs – members of the ‘Ichthyander’ diving club, named after a character from the novel ‘The Amphibian Man’ by Soviet sci-fi author Alexander Belyaev.

They started to assemble the underwater house in Fall 1965. Metal sheets – future walls – were provided to the enthusiasts by the Institute of Mining Mechanics and Technical Cybernetics. The compressor that filled the divers’ tanks with compressed air was found at an airport and repaired. The only power plant at the divers’ disposal was decommissioned, but it, too, came in handy.

The first Soviet underwater house, in its shape, looked like a little hangar with an arched roof; it had an area of six square meters, with the capacity of two people. Inside, there was a bunk bed, a desk with a phone, monitoring and medical devices and a lavatory. Four portholes provided a view outside. Forced ventilation was designed in such a way that the aquanauts could even smoke inside. It was planned that electricity, fresh water and air would be pumped from the shore through pipes and cables; food for the inhabitants – a daily ration of 5,000 calories – was to be delivered by other divers.

On August 5, 1966, the house was brought to Tarkhankut Cape in Crimea. The local sea depths were, by that moment, well explored: ancient amphoras and Scythian household items were found there. On the cape, the divers set up a tent city for 100 people. Engineers and rescue workers were on duty on shore and ensured that the experiment would be conducted safely. Doctors were measuring the breathing, blood circulation, metabolism and mental reactions of the divers. Meanwhile, news camera crews were recording this historical moment. In total, there were three underwater inhabitants.

‘Ichthyander-66’

Archive photoThe first attempt to lower the house to an 11-meter depth with the help of five half-ton concrete blocks was undertaken on August 19, but the plans were foiled by a three-day storm that scattered the blocks around the entire bay. The second, successful attempt was undertaken on August 23. The house was towed to the dive site for two hours on oars, because the boat motor had failed.

The chairman of the divers’ club, surgeon Alexander Haes, became the first inhabitant of the house, escorted to the sea depths by his colleague, Zhora Tunin. The first day Haes spent alone.

“The house was rocking all night. Several times I woke up in horror – I lost my sense of space; sometimes it seemed that the cables were about to snap and I’d have to rush to the exit, but where was it, from what side? Where should I’ve looked for the rock afterwards where the emergency scubas were stored!? Every time, I called our base anxiously, but a confident voice always answered: ‘Sasha, everything is totally fine…’ Now there are no doubts. The experiment, our experiment, was successful…” one of the excerpts from Alexander Haes’ diary in 1976 published by ‘Vokrug sveta’ (‘Around the world’) magazine read.

At 7:30 am on August 24, Haes was visited by the doctors, who checked his health indicators. At 8:30 am, a “waiter” with breakfast went down to him, who later also accompanied Alexander for an underwater stroll. Closer to the evening, he was joined by Dmitry Galaktionov, an engineer from Moscow. Donetsk miner Yuri Sovetov then replaced the pioneer on August 26.

Before surfacing, Haes went through the process of desaturation in the underwater house – the flushing of nitrogen from the body by first inhaling an oxygen-helium mixture and then – pure oxygen. During the surfacing, Haes had his first 20-minute stop at the seven-meter depth. Then another one at the three-meter depth. These pauses had been planned for decompression – a slow removal of excess nitrogen from the body. In 60 minutes, after three days of underwater life, the USSR’s first aquanaut resurfaced alive and in good health.

The following day, on August 27, a storm began. At 8:00 am, doctors managed to dive and check on the health indicators of aquanauts Galaktionov and Sovetov, but, by two in the afternoon, they decided to abandon the entire experiment.

When the ‘Ichthyander’ project team returned to Donetsk, they received a late notice from the Federation of Underwater Sports prohibiting the experiment, but, several months later, the Federation nevertheless awarded the divers with diplomas.

‘Ichthyander-67’ lab before launch

M.Turovsky/TASS‘Ichthyander-66’ gave a start to a series of experiments with underwater houses by Donetsk divers. On August 28, 1967, again in Crimea, in Laspi Bay near Sevastopol, they lowered ‘Ichthyander-67’ to now a 12-meter depth – a four-room house designed for five people, with a kitchen, a bedroom, a bathroom and a laboratory. Aquanauts – now women, too – lived underwater for 14 days in total, in shifts. They tested their organisms for working in unnatural conditions and also brought in guinea pigs, mice, a rabbit and a cat. The divers also happened to test their nervous systems – water leaked into the house twice and, during the second time, it flooded the house half-way.

The last house from the ‘Ichthyander’ series was lowered to the sea floor in 1968, also in Laspi Bay. The aim of the experiment was to conduct geological research: a drilling rig was operating on the seafloor not far from the house, which the aquanauts were maintaining. The project was halted after four days, due to a storm. That was the last experiment by the Soviet amateur divers.

‘Ichthyander-68’

YouTube/Gosudarev BuerakIn 1970, Tarkhankut Cape featured a sign commemorating the first underwater house that said: “Look forward and don’t look back”. In 2006, 40 years after the experiment, three black-and-white checkered plates were installed at the same place, symbolizing the shape of the second ‘Ichthyander’ house.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox