Voices of War: Memories from the Siege of Leningrad

Young participants of Blockade Bread of Leningrad rally holding posters with pages from the diary of "blockade" girl Tanya Savicheva. The rally was held at the Piskarevskoye Memorial Cemetery in St. Petersburg. Source: Vadim Zhernov / RIA Novosti

On the 70th anniversary of the lifting of the Siege of Leningrad, RBTH is going back to the most authentic documents of the blockade days – the diaries of Leningrad residents. Below you will find true stories from one of the most horrific tragedies of WWII, as told by the participants themselves. Not all of the authors managed to survive.

September 8, 1941. Elena Mukhina, 17, high school student:

Today was the first time they announced that German planes are attacking Leningrad. It turns out that a group of enemy planes made it through the defenses, and in the first wave, incendiary bombs were dropped on different parts of the city.

A few fires started in residential buildings and warehouses, but these were quickly put out. (I don’t know about “quickly”, because those fires burned for 5 hours.) Buildings have been destroyed. There are people who are dead and wounded.

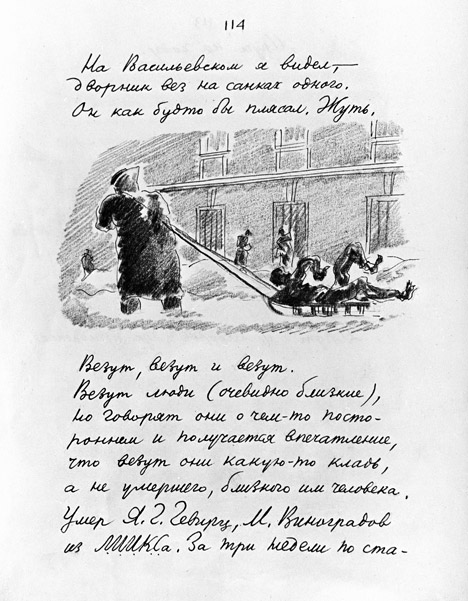

The diary of Leningrad resident. Source: Boris Losin / RIA Novosti

Military installations have not been hit. It’s not even nine in the morning now. A short alarm just ended. It’s strange, though. They sounded the ‘all clear’ some time ago, but I clearly heard the drone of an airplane and the single shots of anti-aircraft guns.

October 3, 1941. Elena Skryabina, 35, teacher of Russian literature:

The bread ration is 125 grams for office workers and dependents, 250 grams for laborers. Our portion (125 grams) is a small piece, as if for a sandwich. Now we’ve started to divide the bread among the entire household — everyone wants to do with his or her bread as they see fit.

View the timeline by RBTH: The chronicles of the Leningrad Siege

For example, my mother tries to divide it up into three pieces. I eat my portion in one go, after my morning coffee: this way, at least I have the strength in the beginning of the day to stand in queues or obtain things via barter. In the latter half of the day I lose my strength; all I can do is lie down.

November 12, 1941. Skryabina:

I visited a lady I know, and she let me try one of her culinary inventions – a jelly made from leather belts. The recipe is: cook belts made from pig leather and prepare a sort of aspic out of it. This nastiness begs description! A sort of a yellowish color and a horrible smell. Despite my extreme hunger, I couldn’t bring myself to swallow even a spoonful, and gagged. My acquaintances were surprised at my disgust; they eat this stuff all the time.

December 22, 1941. Klavdiya Naumovna, a doctor at a Leningrad hospital:

We’ve started to get many severely emaciated patients, and I’ve had to switch [to attending to them]. If you only knew what I’ve had to witness! These aren’t people, rather skeletons with dry skin of a horrible color stretched over them.

Their consciousness is muddied, there’s a kind of dullness and doltishness about them. They lack strength completely. Today I saw a patient like that; he walked to the hospital by himself, but died two hours later.

There are many people in the city dying of hunger. Today a doctor I know buried her father, who also died of emaciation. She says that there are horrible things going on at the cemetery and around it — everyone’s transporting corpses.

December 25, 1941. Mukhina:

I’m so happy, I’m so happy! I want to scream for joy. My God, how happy I am! They’ve given us more bread! And a lot, too. What a difference: 125 grams versus 200 grams: 200 grams for office workers and dependents; 350 grams for laborers.

I’m telling you, it’s salvation, pure and simple; lately we’d all grown so weak that we were barely shuffling our feet. And now — well, now, Mum and Aka, they’ll survive. This is what makes me so happy. This, and the fact that this is the beginning of an improvement. Now, things will begin to improve.

January 6, 1942. Lyubov’ Shaporina, artist, founder of the first Soviet Puppet Theater:

This morning I was going to work and my legs were shaking. There is so much to do at the hospital. Four subcutaneous injections for people fading away; being present at the operating table; running up and down… I barely dragged myself home. I came in and fell into bed.

The will to live is fading. My heart aches. I can’t believe that I might not make it… People with buckets are walking the streets, looking for water. Most buildings don’t have water; the pipes are frozen. There is no firewood. Fortunately, we often have water, and right now we have electricity. There are no letters from anyone. It’s snowing. We’re all going to die, and the snow will cover us.

January 7, 1942. Skryabina:

About an hour ago, a fellow my husband knows by the name of Pyotr Yakovlevich Ivanov, came by. This young man, always happy and full of energy, has now changed beyond recognition: he’s gaunt and pale, and somehow strange.

It’s as if hunger were turning everyone into lunatics. It turns out that he came to find out whether the large grey tomcat that a singer who lived in our house used to have is still living. He was hoping that the cat had not yet been eaten, as he knew how much the singer had adored it. I was forced to disappoint him – there is not a single living thing in our house, save for the people who are barely putting one leg in front of the other.

January 16, 1942. Skryabina:

The outpatient clinic is full of laborers and office workers who are so bereft of strength that they can’t continue working, but, afraid of being branded truants, come here for doctor’s notes. When they get here, many of them die in the queue to see the doctor. The floor in this building is literally thick with the dead and the dying. The people taking them away can’t do so fast enough.

January 17, 1942. Shaporina:

Yesterday I was walking past the Summer Garden. The trees were hoary with a downy, beautiful frost. Towards me comes a man of about 40, as gaunt as can be, with a genteel exterior. Dressed well, in a warm overcoat with a [thick] collar.

His nose is sharp and has, as the noses of many now do, a purple bruise on the hump of it. His eyes are open wide, about to fall out. He walks along, barely moving his limbs, his arms clutched to his chest, and repeats in a hoarse, quivering voice, “I’m freezing to death, I’m free-ee-z-zing.”

June 18, 1942. Shaporina:

Very interesting books are showing up at the bookseller’s on Simeonovskaya [street] and, instead of saving up for a casket, I’m hunting for books. It’s crazy. One bomb is all it will take to wipe it all out. But no one is thinking of that at all.

July 15, 1942. Klavdiya Naumovna:

Nothing’s changed. During the day, there is shooting, often… but life goes on and, I would even say, full speed ahead compared to the winter. The people are clean; they’ve started to wear nice dresses.

The tram is running, shops are opening up bit by bit. There are queues at the perfume shops — there’s been a delivery of perfume to Leningrad. Although a tiny bottle costs 120 rubles, but people are buying, and I’ve got a bottle as a present. I was very happy; I love perfume so! I put some on myself and I feel like I’m not hungry, like I’ve just returned from a concert or a restaurant.

August 6, 1942. Vladimir Bogdanov, 21, machinist:

Bloody sick of it all, and it’s summer. What’ll happen when winter comes and nothing’s changed? Not likely that we’ll weather the winter if things continue like this. On the other hand, my mind is set as far as evacuation goes: Dad and I don’t have anywhere to go, or anything to take with us, so we’ll remain here until the end. I can’t leave behind the city where I was born and lived all 20 years of my life, the city that’s so dear to me, the city that’s become so bleak and inhospitable during the war. I can’t leave it behind.

Based on the "The Blockade Book" ('Leningrad Under Siege: First-hand Accounts of the Ordeal') by Daniil Granin and Ales Adamovich (1977-1984).

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox