Novgorod the Great (Veliky Novgorod). Cathedral of St. Sophia, south view. March 14, 1980

William BrumfieldAt the beginning of the 20th century, Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography.

His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated with special clarity through his photographs of medieval architecture in historic settlements northeast of Moscow such as Vladimir, which he visited in the Summer of 1911.

Vladimir. Dormition Cathedral, northeast view. Right: Regional Administrative Building (1785-90). Summer 1911

Sergey Prokudin-GorskyAmong his several views of the town are two photographs of the monumental limestone Dormition Cathedral. Completed in 1158 by Prince Andrei Bogoliubsky (?-1174), the Dormition Cathedral was rebuilt in a larger and more complex form during the reign of his half-brother, Vsevolod III (1154-1212). The impetus for the expansion stemmed from a fire in 1185 that destroyed much of Vladimir and severely damaged this central cathedral.

Veliky Novgorod. Fortress (detinets), view across Volkhov River. From left: Bell Gable, St. Sophia Cathedral, St. Nicetas Wing, Vladimir Tower. May 19, 1995

William BrumfieldIn reconstructing the Dormition Cathedral in 1185-1190, Vsevolod's builders dismantled the attached galleries, but retained the smooth limestone walls of the original structure as the core of the rebuilt cathedral, encased on three sides with new aisles. The cathedral was crowned by four secondary domes placed diagonally to the main dome.

The resulting grand structure conformed to an elongated plan with a large central dome typical of major shrines in Novgorod, such as the Cathedral of St. Sophia, built almost 150 years earlier. Although constructed of different materials, the two cathedrals show important similarities in adapting Byzantine traditions to the territory of early medieval Rus’ (as the lands of the Eastern Slavs were collectively called).

Cathedral of St. Sophia, southeast view. Main apse with south gallery (left) & apse of Chapel of Nativity of Virgin, to the right of which is the 16th-century Chapel of Sts. Joachim & Anna. May 27, 1998

William BrumfieldOfficially referred to since 1999 with its medieval designation ‘Novgorod the Great’ (‘Veliky Novgorod’), this northwestern Russian city near Lake Ilmen is a magnificent repository of medieval Russian art, with more than fifty churches and monasteries extending from the 11th to the 17th centuries. In 1992, this wealth of historic monuments – centered on the Novgorod Kremlin or ‘detinets’ – was honored by inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Medieval chronicles first mention Novgorod between 860 and 862, when the eastern Slavs summoned Varangian leader Rurik to assume control of their affairs. Although the Rurikovich rulers transferred power to Kiev at the end of the 9th century, Novgorod continued to exercise control over a vast area of northern Rus’.

Cathedral of St. Sophia, east facade. Apse with detail of original plinthos brickwork beneath stucco. March 27, 1991

William BrumfieldIn 989, following the official acceptance of Christianity in the domains of Grand Prince Vladimir of Kiev, Novgorod was visited by Vladimir's ecclesiastical emissary, Bishop Joachim of Kherson. The bishop overturned pagan idols into the Volkhov River and commissioned the first stone church, dedicated to Sts. Joachim and Anna, as well as the wooden Church of St. Sophia, with thirteen "tops" (domes).

The political history of Novgorod was far from calm, for the city not only frequently challenged its leaders, including Rurik, but also participated in the princely feuds that wracked the Kievan state. Nevertheless, Novgorod prospered during the 11th and 12th centuries, as part of the Dnieper trade route from the Baltic to the Black Sea. With its mercantile wealth, the city had the means to create a citadel and an imposing architectural ensemble of churches.

Cathedral of St. Sophia, northeast view with north gallery & apse of Chapel of St. John the Divine. March 14, 1980

William BrumfieldThe Volkhov River, which separated the city into the ‘Trading Side’ and the ‘Sophia Side’ (after the Cathedral of St. Sophia), provided an essential link for trade and exploration within a network of waterways that led in every direction. The extent of this commercial activity produced literate citizens independent of Kiev and its representative in Novgorod (usually, the brother or son of the grand prince in Kiev).

The oldest surviving and most imposing monument in the city is the Cathedral of St. Sophia (Divine Wisdom), built between 1045 and 1050 and located in Novgorod's ‘detinets’ or kremlin on the west bank of the Volkhov River. The cathedral was commissioned by Vladimir Yaroslavich, the prince of Novgorod, as well as by his father, Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and by Archbishop Luke of Novgorod.

Cathedral of St. Sophia. West facade, center bay with fresco of Old Testament Trinity. March 14, 1980

William BrumfieldIt is fitting that Yaroslav, whose own Sophia Cathedral in Kiev was entering its final construction phase at this time, should have played a role in the creation of the Novgorod’s St. Sophia. Novgorod had been the base of his power during the reign of his father, Grand Prince Vladimir of Kiev.

Cathedral of St. Sophia. West facade, center bay with Sigtuna Door. November 18, 1979

William BrumfieldWith the building of large masonry cathedrals dedicated to the Divine Wisdom in both Kiev and Novgorod, Yaroslav rendered homage to one of the most sacred mysteries of the Orthodox Church and established a symbolic link between the two major cities of his realm and Constantinople.

In addition, Yaroslav's participation would have been essential from a practical point of view. Masonry construction was rare in Novgorod before the middle of the 11th century and a cathedral of such size and complexity could only have been constructed under the supervision of experienced builders.

Cathedral of St. Sophia, interior. Central crossing under main dome. May 19, 1990

William BrumfieldThey applied a method of placing blocks of local rough gray limestone within a mortar of crushed brick and lime that imparted a pink hue to the coarsely textured façades. Narrow plinthite (an iron-rich, humus-poor mixture of clay with quartz and other minerals) brick was used for the interior arches and vaulting, as well as for other segments that required structural precision. Stucco was first applied only in the interior, which was then covered with frescoes painted by local and foreign masters from Greece and the Balkans.

On the exterior, the cathedral walls presented a highly textured appearance, even after cladding with mortar to reduce the unevenness of the surface. The earliest reference to the application of whitewash to the walls appears in the Novgorod chronicle in the year 1151.

Cathedral of St. Sophia, interior. View east from choir gallery toward icon screen & central apse. March 27, 1991

William BrumfieldThe Novgorod cathedral included enclosed galleries attached to the north, west and south facades. Originally intended to be only one story, the galleries evolved during the building of the Novgorod cathedral into an integral part of the structure on both levels. The north and south galleries contain chapels on the ground level, while the west gallery includes a round stair tower that leads to the upper gallery levels, including the choir gallery in the main structure.

The facade above the west portal displays fragments of a medieval fresco depicting the Old Testament Trinity. The portal itself contains the bronze Magdeburg or Sigtuna doors, produced in Magdeburg in the 1050s and taken as loot from the Varangian fortress of Sigtuna by Novgorod raiders in 1117.

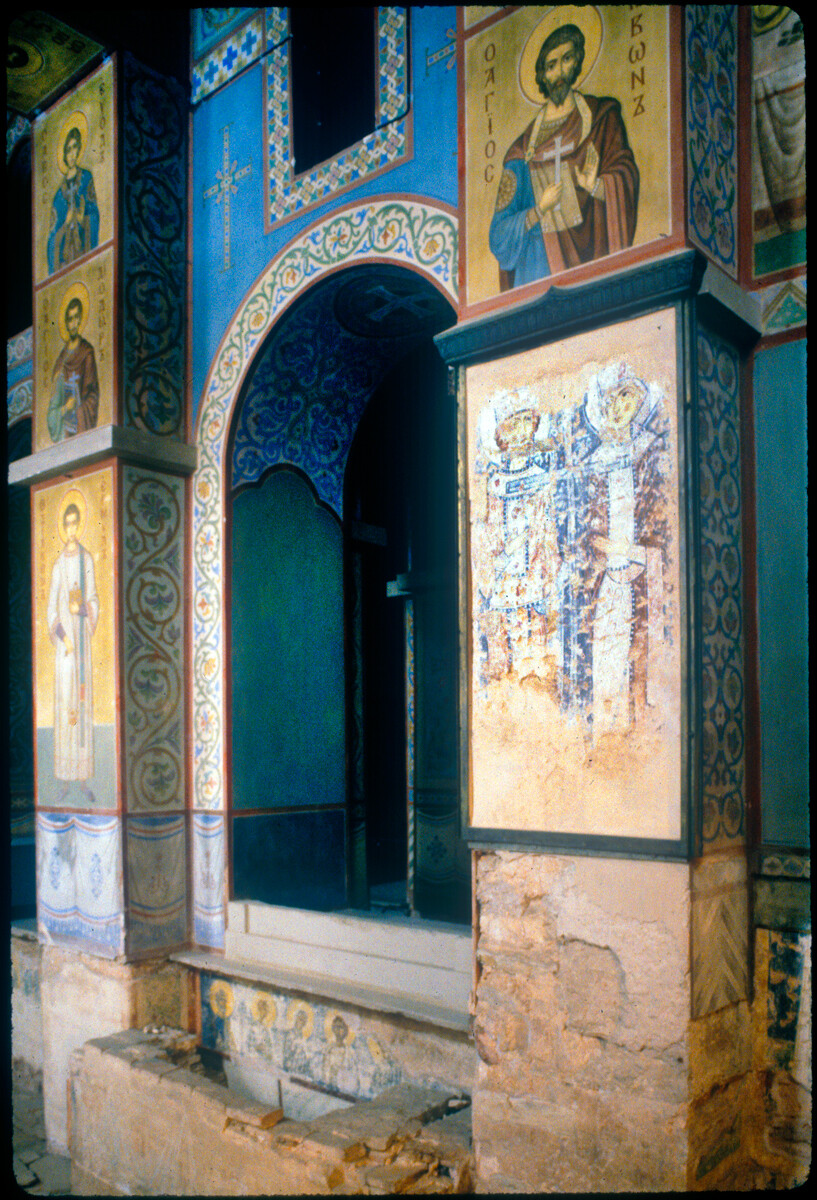

Cathedral of St. Sophia, interior. North wall of southeast gallery with 19th-century wall paintings & 12th-century frescoes of Sts. Constatine & Helen (right). March 27, 1991

William BrumfieldThe culminating point of the Novgorod St. Sophia Cathedral is its ensemble of cupolas, whose original form would have had a lower pitch than the helmet-shaped domes now in place. The dome over the central crossing predominates in height and diameter, yet the four subsidiary domes are so closely placed, as to appear part of one perfectly devised whole. the structure itself provides a visual base for the domes, with its lack of surface decoration and sharply etched roof line of pointed and arched gables (‘zakomary’).

Cathedral of St. Sophia, interior. West wall of southeast gallery with 19th-century wall paintings & excavation showing original level of main floor. March 27, 1991

William BrumfieldThe cathedral was flanked with enclosed galleries attached to the north, west and south facades. Originally intended to be only one story, the galleries evolved into an integral part of the structure on both levels. The north and south galleries contain chapels on the ground level, while the west gallery has a stair tower that leads to the upper galleries. The emphasis on height is maintained in the interior where the piers of the main aisles soar directly to the barrel ceiling vaults.

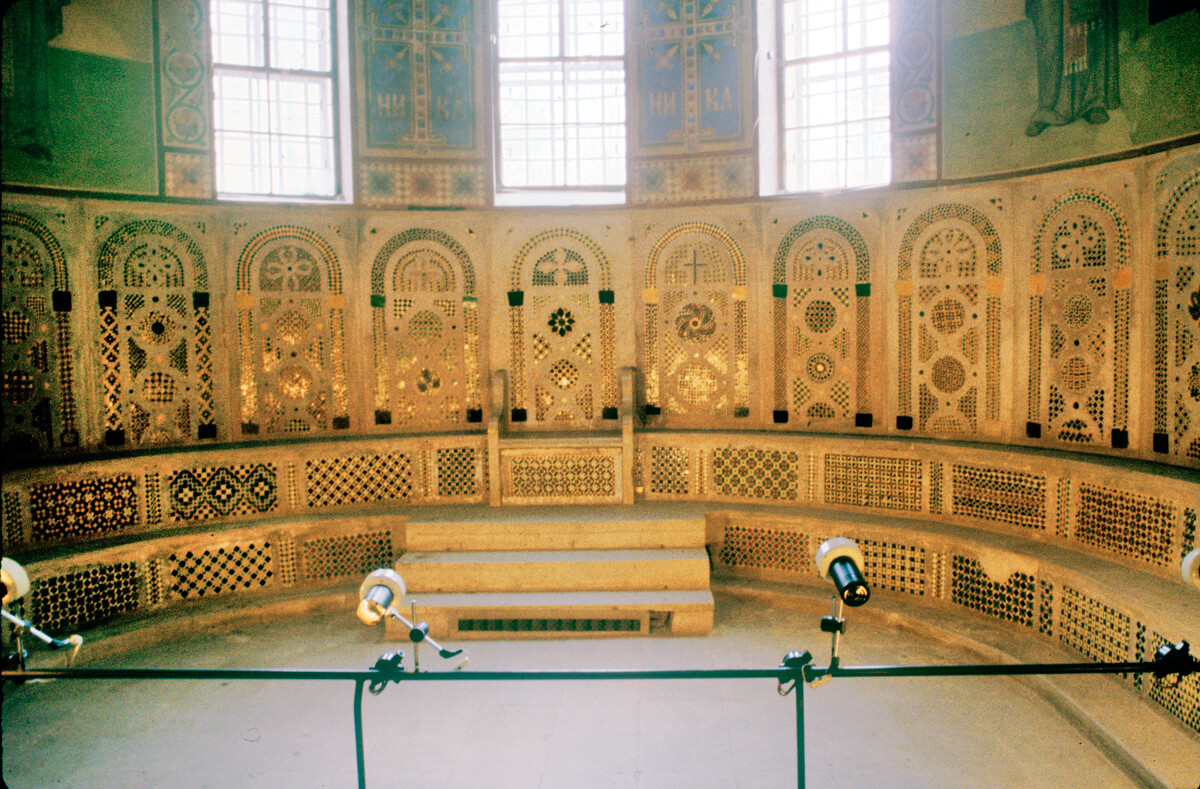

Cathedral of St. Sophia, interior. Central apse with decorative masaic panels (late 11th-century with 19th-century restoration). March 27, 1991

William BrumfieldNovgorod chronicles indicate that the interior was painted with frescoes over a period of several decades.

Cathedral of St. Sophia, interior. Central apse with 19th-century wall paintings. March 27, 1991

William BrumfieldAccording to the Third Novgorod chronicle, soon after the completion of construction "icon painters from Tsargrad (Constantinople)" painted Christ with his hand raised in blessing (probably an image of the Pantocrator in the central dome) and other representations of the Savior. Fragments of the 11th-century work – including full-length paintings of Emperor Constantine and his mother Elena – have been uncovered, as well as early 12th-century frescoes.

Cathedral bell gable (zvonnitsa). March 14, 1980

William BrumfieldMost of the original painting of the interior has vanished under centuries of renovations (The current frescoes date primarily from the 19th century).

Evfimiev Clock Tower, east view. May 20, 1990

William BrumfieldThe Novgorod cathedral lacked the elaborate mosaics characteristic of major churches in Kiev before the mid-12th century, yet there was decorative mosaic work on the floor and in the altar space.

Facated Chambers with 19th-century exterior. May 29, 1992

William BrumfieldThe St. Sophia Cathedral is surrounded by an array of historic monuments that include the massive Cathedral Bell Gable (15th-18th centuries), the Clock Tower (now dated to the 1670s) and the Archbishop's Chambers – also known as the Faceted Chambers, originally built in the 1430s and substantially rebuilt in the 19th century.

Novgorod citadel (detinets), Vladimir Tower. March 13, 1980

William BrumfieldThe fortress walls and towers have been maintained and restored to a 15th-century appearance, although some of the towers date to the late 13th century.

Novgorod citadel (detinets), Feodor Tower. March 13, 1980

William BrumfieldFacing the St. Sophia Cathedral to the south is the gargantuan bell monument known as the ‘Millennium of Russia’. Designed by the sculptor Mikhail Mikeshin and others, the monument was unveiled in 1862 to honor the millennium of the founding of dynastic authority among the ancient Rus.

Novgorod citadel (detinets), Monument to Millennisum of Rus. May 29, 1992

William BrumfieldAt the top of the monument is a massive bronze globe surmounted by an angel holding a cross. Around the sphere are six statuary groups signifying defining moments in the history of Russian statehood, from Rurik, founder of the first dynasty, to Peter the Great, founder of the Russian Empire.

Monument to Millennisum of Rus. From left: Novgorodian overturning statue of pagan god Perun, Prince Rurik, Prince Dmitry Donskoy with subdued Tatar. May 29, 1992

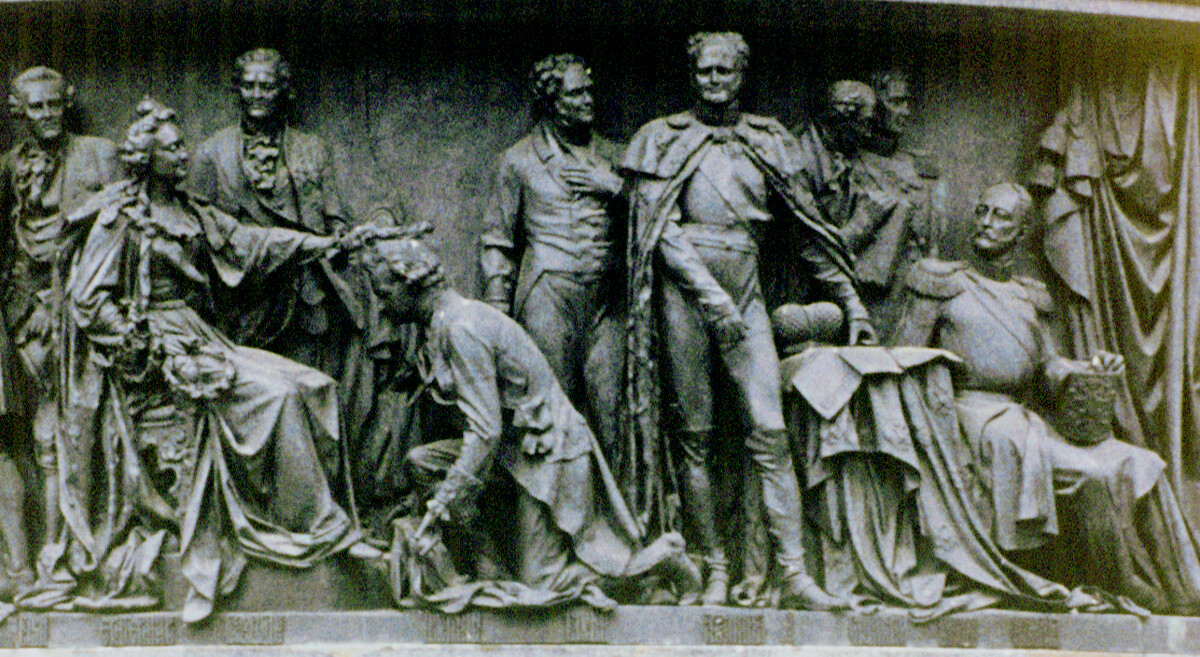

William BrumfieldAt the bottom of the bell are scenes with exemplary figures from spiritual, cultural, state and military service.

Monument to Millennisum of Rus. From left: Ivan Betsky, Cathedrine the Great, Alexander Bezborodko, Grigory Potemkin, Viktor Kochubey, Alexander I, Mikhail Speransky, Mikhail Vorontsov, Nicholas I. June 4, 1993

William BrumfieldIn the early 20th century, Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916, he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century, the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986, architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox