Ludmila Ulitskaya's new novel explores human frailty with compassion

Ludmila Ulitskaya.

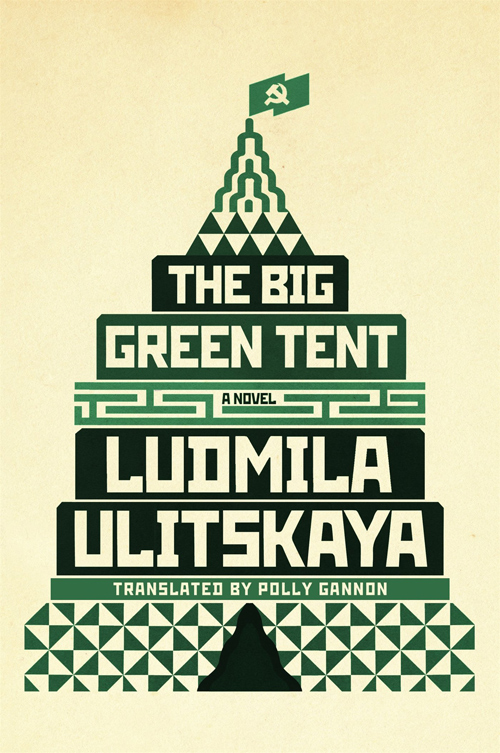

Getty Images/FotobankLudmila Ulitskaya’s evocative book The Big Green Tent (2010), set in Moscow after Stalin’s death, has just appeared in Polly Gannon’s elegant English translation. It is Ulitskaya’s sixth novel translated into English and as readable as ever. Her New York-based 2002 novella, The Funeral Party, celebrated the lives of Russian émigrés. Daniel Stein: Interpreter(2007), which explored religion and philosophy through a mosaic of real and invented texts, won the Russian Big Book prize and was nominated for the International Man Booker.

Fraught and mangled histories

The Big Green Tent is Ulitskaya’s longest novel yet (almost 600 pages) and has an openly Tolstoyan ambition to capture the spirit of an age. She adopts a relatively conventional narrative style, but a deliberately erratic timeline, letting one tale race to its conclusion, only to bounce back to earlier days like a temporal yo-yo. Ulitskaya looks sideways at her earlier postmodernism: “Culture has become a patchwork, a web of citations.” Occasionally she repeats whole sentences, even paragraphs, reinforcing social patterns as she traces individual trajectories. She hints that modern life, “complicated and splintered”, is hard to recreate in linear form.

The Big Green Tent is Ulitskaya’s longest novel yet (almost 600 pages) and has an openly Tolstoyan ambition to capture the spirit of an age. She adopts a relatively conventional narrative style, but a deliberately erratic timeline, letting one tale race to its conclusion, only to bounce back to earlier days like a temporal yo-yo. Ulitskaya looks sideways at her earlier postmodernism: “Culture has become a patchwork, a web of citations.” Occasionally she repeats whole sentences, even paragraphs, reinforcing social patterns as she traces individual trajectories. She hints that modern life, “complicated and splintered”, is hard to recreate in linear form.

Many of Ulitskaya’s recurring topics are here: Judaism, feminism, families. The novel looks back to the Decembrists, a parallel history of dissent, and glances covertly towards the present day. She narrates a drunken teenage party or a KGB interrogation with the same eye for comic detail, the same ear for ominous cadences.

The interlocking stories in The Big Green Tent revolve around three male and three female school friends. The novel opens with the disparate reactions of their families to news of Stalin’s death, from Olga’s mother, a party official, (“misfortune has befallen us”) to Tamara’s grandmother, who wants to celebrate that: “the Big S seems to have kicked the bucket.” What follows are the fraught and mangled histories of those who (as Ulitskaya writes in her acknowledgments): “stumbled into the meat grinder of their time … the witnesses, the heroes, the victims…”

The three boys first bond whilst rescuing a stray kitten from two bullies. Mikha, orphan, poet and – later - teacher, is red-haired, “bespectacled and a Jew, to boot”; Sanya is musical, sensitive, a repressed homosexual. Ilya, tall and dynamic, becomes a dissident publisher and photographer. Their schooldays, “full of enemy spies” and “skirmishes”, mockingly prefigure later sagas of betrayal and compromise, exile or suicide.

Skirting the eternal puddles

“The great truth of literature” is an overarching theme. Ulitskaya’s pages are sprinkled with references to Solzhenitsyn, Brodsky, Zamyatin, Dickens and Orwell, classical myths or samizdat manuscripts. A war-wounded teacher, Victor Shengeli, arrives at the boys’ school and forms a Dead Poets Society-style club called LORL (the Lovers of Russian Literature). He leads the boys through the streets of Moscow, whose shifting history and geography are potent undercurrents in the novel’s narrative tide.

“We live not in nature, but in history,” Ulitskaya writes, as her protagonists walk down a lane once trodden by Pushkin and Pasternak, “skirting the eternal puddles.” One house, in whose storeroom two of the boys lose their virginity, provides a physical metaphor for Moscow’s historical strata: “its walls had been covered in silk, then in empire wallpaper, … later in crude oil paint, … then layers of newsprint.”

The book’s title image comes from a dream that one of the characters has of “a large green marquee” filled with “the dead and the living … together.” The imaginary tent embodies the spirit this generous, inclusive novel, spanning more than four decades of Soviet life. Ulitskaya’s defining characteristic, here as it was in Daniel Stein, is an overwhelming compassion for human frailty. After the unexpected death of an enemy, Mikha feels: “pity of enormous proportions … for all people, both bad and good, simply because they were all so defenceless and fragile.”

Read more: Ludmila Ulitskaya: Culture is above politics and public life

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox