Little known masters of Soviet dissent make waves in D.C.

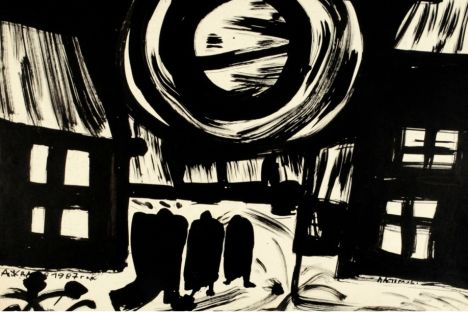

The exhibit “Lest We Forget: Masters of Soviet Dissent” by Charles Krause offers some nonconformists from the former Soviet Union. Source: Leonhard Lapin, Alexander Zhdanov

The exhibit closes this weekend, but his posh private gallery in D.C. offers a new, and rare venue for dissident art, including the lesser-known nonconformists from the former Soviet Union.

Russia Beyond The Headlines: How did you first become interested in the dissident artists of the Soviet Union?

Charles Krause: I spent most of 1991 in Moscow reporting the turmoil and, finally, the collapse of the Soviet Union for the old MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour, now the PBS NewsHour. Although I was mostly interested in collecting Soviet propaganda art at that time, I became aware that there were other artists who had refused to paint in the official style. But it wasn't until 2003 or 2004 that I first saw their work and learned their names when I went to see a brilliant exhibit at the Tretyakov Gallery, half of it work by Andy Warhol from the 60s, 70s and early 80s and half work by Russia's Nonconformist artists from the same period. I was stunned, amazed, simply blown away by what I saw and vowed to myself that I would learn as much as I could about them and build a collection of their art – both because many of them were extraordinarily inventive and original and because of the example they set and the risks they took to create art that, in and of itself, made a political statement even if there was nothing else political about it.

RBTH: What attracted you to Leonhard Lapin’s work specifically?

The exhibit “Lest We Forget: Masters of Soviet Dissent” by Charles Krause. Source: Leonhard Lapin, Alexander Zhdanov

C.K.: I first saw Leo's work five or six years ago at Ilona Anhava's gallery in Helsinki, which I consider to be one of the two or three best galleries in the world. Ilona has unerring good taste, exhibiting art by Finnish, Russian and other northern European artists whom no one in the United States has ever heard of. I admired Leo's recent work, the work Ilona was showing, but when she told me about the work he had done when Estonia was still a part of the Soviet Union, I asked her if she would call him and arrange for me to meet him at his studio in Tallinn. When I got there and he began pulling out his "Machine Series" drawings from the '70s and his "Conversation of the Signs" silk screens from the late 80s and early 90s, I knew I was seeing the work of a master draughtsman and colorist whose work was political, overtly anti-communist and anti-Soviet, an artist whose art had helped keep alive the dream of a free, independent Estonia and that actually did influence political events at one of the most critical moments of our contemporary history.

RBTH: Why is he not as well known as other masters of Soviet dissent, in your opinion? How do you hope that might change?

Related :

The man who flew into space from his apartment

Artist Yevgeniy Fiks examines historical ironies in his DC show

C.K.: Leo was not in Moscow or Leningrad, he was in Estonia, and therefore was not as well-known as the other dissident artists to the journalists and diplomats who consorted with these "ant-Soviet elements," buying their work and bringing it home. When the Soviet Union collapsed and Sothebys and Christies rushed in to fill the void, there was enough great work by the Nonconformist artists from Russia's two major cities that no one needed to look beyond their noses. And no one but Norton Dodge, the American collector who amassed the greatest collection of Nonconformist art in the world, did. So Leo and Alexander Zhdanov, for different reasons, have been largely ignored by Western collectors and the auction houses –not because they weren't as good or better than the Russian dissidents whose work now sells for hundreds of thousands of dollars but because they simply remain obscure and largely unknown. I hope to change that by showing their work, in the belief that others will see the value. I should add that Norman Dodge continued to collect both Lapin's and Zhdanov's work long after the Soviet Union collapsed because he did see the value.

RBTH: Why did you and your colleague Mark Kelner decide to couple Lapin with Alexander Zhdanov? What do they have in common and how does their work contrast?

C.K.: Mark greatly admired Norman Dodge and, despite the difference in their ages, knew him quite well. So it wasn't difficult to convince him that the two could, and should, be shown together because Mark was well aware of Dodge's admiration for both artists. That was important because Mark represents the Zhdanov estate (Zhdanov died in Washington in 2006 after having been expelled from the Soviet Union in 1987), so the show couldn't have been done without him. Why show Lapin and Zhdanov together? Because in my view, both were great artists working in the same country, under the same pressures, at the same time. Yet their work is very different, Leo's being precise and overtly political while Zhdanov's work is more abstract and emotional, conveying the unending drudgery and emptiness of life under communism. Seeing them together demonstrates, if nothing else, that Russia's Nonconformist artists didn't rebel against the official Soviet realism style only to end up with a single official style of their own. They rebelled because they wanted to be free to express themselves and once they were free, their talent and creativity took them in many different directions.

RBTH: Tell us about “Charles Krause Reporting Fine Art/Gallery. Why did you decide to open a gallery in your home? What do you hope to achieve, culturally and socially, in a political town like Washington, D.C.?

C.K.: I opened my gallery in my home because I had a limited amount of money to invest and thought the money would be better spent bringing quality work from Europe and elsewhere – the kind of work I had collected myself as I moved around the world reporting on wars and revolutions as a foreign correspondent – than on renting a big space that would have limited my ability to show the kind of work I think is important. My goal is not only to sell art. It is to expand the definition of what makes great art to include its impact on society, both our values and the way we govern ourselves. What I hope to achieve is stated very clearly on the Homepage of my website, www.charleskrausereporting.com.

"I will exhibit and sell fine art I admire for its quality and originality as well as its social and political significance. I will also show work by artists I admire for the risks they have taken to defend their artistic freedom and/or the political and human rights of others. By showing the work of these artists, I hope to influence the way their art is viewed, understood and valued by museum curators, art historians, art critics and collectors throughout the world."

I may be crazy. But I think it's worth a try.

Charles Krause: His Story

Charles Krause’s interest in the art of social and political change developed over the course of his career as a foreign correspondent for The Washington Post, CBS News and The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. On assignment in Latin America, Central Europe, Russia, Asia and the Middle East, he witnessed many of the wars and revolutions of the last two decades of the 20th Century. His coverage earned him an Emmy Award for his reporting from Israel and the Middle East in 1997, the Latin American Studies Association Media Award for his reporting from Central America in 1987, and the Overseas Press Club’s Hal Boyle Award for his reporting from Jonestown, where he was shot and wounded while on assignment for The Washington Post, in 1978.

Krause is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania where he was editor-in-chief of The Daily Pennsylvanian and the University's first Young Alumni Trustee; and Princeton University's Woodrow Wilson School (MPA). He is currently president of the American Friends of the Gdansk Theatre Foundation and a member of the Inter American Foundation's international advisory board. His gallery, CHARLES KRAUSE/REPORTING FINE ART, opened in December 2011. Its first exhibit showed work by the artist who designed the Solidarity trade union logo and was titled "The Graphic and Fine Art of Poland's Jerzy Janiszewski: The Artist Whose Graphic Design Changed History." The gallery 's second show, "Duva Diva: DuvTeatern's Glorious Carmen: Photographs by Stefan Bremer," presented 15 portraits of actors and actresses with Down Syndrome and other developmental disabilities. The current exhibit, "LEST WE FORGET: Masters of Soviet Dissent," opened May 7th and will close this Sunday, July 22nd.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox