Kaluga Space Museum: From the countryside to the stars

Russia's State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in the Kaluga Region retraces the history of astronautics from its early days to modern times. Source: Press Photo

Lying some 125 miles south of Moscow in Kaluga Region, high above the shores of the Oka River, there stands a bright white rock with a conic rocket mounted atop it. There is no surprise that Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics has a futuristic appearance: both Sergei Korolyov and Yuri Gagarin were involved in its construction in the early 1960s.

View Larger Map |

The museum retraces the history of astronautics from its early days to modern times. Among the various exhibits are rockets, motors and spacesuits – some of which have made the trek to outer space. There was a flurry of activity in the cosmonautics museum in early April. A special exhibition about Gagarin was being put together and invitations were being sent out to cosmonautics veterans for the “Man, Earth, Cosmos” conference. Museum curator Yevgeny Kuzin entered the building, after observing specialists outside who were appointed to set up the Vostok rocket, which has stood in front of the museum since 1973.

“Should I send his letters to Gagarin [Museum] now?” His assistant asked. “Fine, send them. After all, the president himself will be attending,” answered Kuzin.

Yuri Gagarin’s letters were sent to a museum in the pilot’s home town in Russia’s Smolensk Region. On April 12, 1961, Gagarin became the first man in space. After his death in 1968, the town previously known as Gzhatsk was renamed in his honor.

|

| Space Museum curator Yevgeny Kuzin. Source: Press Photo |

Kuzin did not begrudge the museum in Smolensk its presidential visit by Dmitry Medvedev. After all, the museum in Kaluga, which Kuzin has been in charge of for 24 years, is the most important cosmonautics museum in Russia. In 2011, during the 50th anniversary of Gagarin’s orbit, 180,000 visitors were set to visit the museum and experience how the dream began and came true. The museum is the first of its kind anywhere in the world. Just two months after the flight that paved the way for humanity to explore space, Gagarin laid the foundation for the Tsiolkovsky State Museum of Cosmonautics in Kaluga.

Why found a museum here, of all places, 125 miles southwest of Moscow and above the idyllic backdrop of the Oka River?The answer lies inside. The exhibit begins with humanity’s earliest attempts at flight: Leonardo da Vinci’s airplane models, the Gondolfier Brothers’ hot-air balloons and Otto Lilienthal’s gliders. The hall then opens up to a multi-stage silver booster, very reminiscent of the illustrations in From the Earth to the Moon.

This is, however, the model of an all-metal airship that was conceptualized by Russian astronautic visionary Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in 1892.

Tsiolkovsky was born in 1857 and lived the majority of his life in Kaluga and surrounding cities. Deaf since childhood, Tsiolkovsky made a living as a professor of mathematician and physics, spending his free time constructing and testing flying objects. Although his work on the theory of flight was published in Russian journals, his contemporaries viewed him as an eccentric.

Related:

Women find space worth the risk

Space Exhibition: Utopia became a reality

“He foresaw so many things,” said Kuzin. “His 1882 work on the effect of zero gravity on human beings was later confirmed in reality.”

There is a reason why cosmonauts later said that the first person in space was Tsiolkovsky. The scientist died in 1935 and thus never saw his ideas come to life. Tsiolkovsky now rests beneath a memorial in Kaluga, just a few feet away from the museum.

Here, visitors can read his most famous quote: “The Earth may be the cradle of humanity, but no child remains in its cradle forever.”

{***}

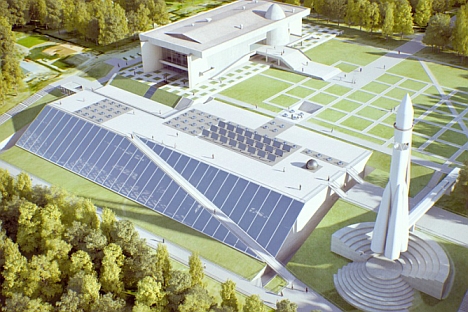

Russia's State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics in the Kaluga Region. Source: Press Photo

The central theme of the cosmonautics museum in Kaluga is the visionary work of Konstantin Tsiolkovsky. Both the scientist’s house in Kaluga and apartment in the city of Borovsk, where Tsiolkovsky spent several years of his life, are a part of the museum. In the museum’s largest exhibition hall visitors can get an up-close and personal look at how Tsiolkovsky’s ideas were transformed into reality by man in the second half of the 20th century. There is a shiny silver replica of Sputnik 1, which circled the Earth in 1957. By request, museum staff can turn on the peep tone that could be heard by hobby radio operators around the world for 26 days.

One exhibit especially fascinates students who make the pilgrimage to the museum: an approximately 655-foot-long device with mounted hoses and a glass ball. In capsules such as these, the dogs that made test flights to outer space in the 1950s were carried back to Earth.

“Out of a total of 52 dogs, only four failed to return,” said Irina Selyunina, exhibit conceptualizer. Younger visitors also particularly enjoy the planetarium, which just last year was equipped with a new Zeiss system.

On display in the museum, there are even two original space capsules that were used by cosmonauts to return to Earth — including the Vostok 5 that returned Valery Bykovsky to Earth in 1963. The outer capsule contains powder traces that were left upon re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

“It’s nice being back in one of these capsules” is written on a seat inside the capsule. Bykovsky himself left the engraved message, during a visit to the museum.

Related:

Gagarin: Universal hero who opened up the heavens

There are space suits to behold, samples of moon rocks, hammers and screwdrivers that were specifically designed for zero gravity , and, of course, world-famous space food: mini pieces of bread, coffee and cream, and Russian cabbage soup – all freeze dried. “Cosmonauts,” said Selyunina, “actually say it didn’t taste nearly as bad as it looks.”

The museum’s main room teems with model rockets, motors and lunar vehicles.

“When the museum was being built, no one could have imagined how quickly astronautics would advance,” said Kuzin, smiling.

An expansion is in the works that will increase the exhibition area fourfold. Construction could begin as early as next year. The expanded museum will hold a model of the Russian space station MIR, which visitors will be able to enter.

According to Kuzin, the new building is slated to cost an additional 40 million euros ($52.2 million). For now, the curator is somewhat impatiently awaiting financing from the Russian Ministry of Culture.

One of the only things Tsiolkovsky could not foresee was when exactly man would successfully complete the first manned flight into space. Tsiolkovsky predicted this would happen in the year 2000 – Gagarin beat him by 39 years.

Info: The Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky State Museum of the History of Cosmonautics is open Tuesday through Sunday. Tours are available in English, French and German. Register by calling: +7 4842 745004. More information is available at http://www.gmik.ru/index_en.html.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox