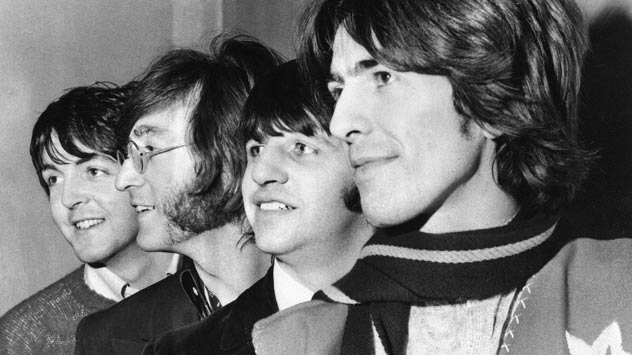

Russia remembers The Beatles

"In the rock ‘n roll of Elvis and the ballads of the Beatles we discovered more meaning than in all the articles by Lenin that we were made to read and summarize in school and at university", says rock musician Alexej Rybin. Source: AP.

When John Lennon was shot by a fanatic in December 1980, his murder shocked Soviet fans no less than it did those who learned of his death from the global media. In Russia, before the news was relayed in all major cities, the first to hear it were those who were tuned in to Western radio stations.

On that tragic day, several hundred students held a spontaneous memorial service in front of Moscow University, as Britain’s Daily Telegraph reported. According to Leonid Parfyonov, a distinguished journalist and author of an encyclopedia of Soviet history, there was no less of a Beatles cult in the Soviet Union than there was anywhere else in the world.

Today, as the world celebrates the Beatles’ 50th anniversary and Sir Paul McCartney’s 70th birthday, the slogan “Lennon lives” remains very popular in the former Soviet Union. “In the rock ‘n roll of Elvis and the ballads of the Beatles we discovered more meaning than in all the articles by Lenin that we were made to read and summarize in school and at university,” wrote rock musician Aleksei Rybin.

Music critics and historians are still arguing about how the Beatles managed to penetrate the Iron Curtain; but exactly when the band was first officially mentioned in the Soviet press is not a matter of debate. In 1964, the London correspondent for the youth newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda published an article about John Lennon and his popular group the Beatles. Boris Gurnov later said that his bosses at Pravda, at first, had a dull opinion of his idea to meet with Lennon.

“At the time, the Soviet press saw this as a ‘bourgeois eccentricity in art’,” Gurnov said. “I wrote a long piece in which I tried to analyze the appeal of the Beatles for young people. I attributed it to certain Freudian complexes – Beatles’ fans were mostly at the age of adolescence.”

Gurnov was probably right about one thing: Soviet censorship was afraid of this exploding energy and kept a keen eye on those Western trends perceived as dangerous. Meanwhile, Soviet Beatles fans collected facts about the group, crumb by crumb. They got their information from rare Western newspapers or magazines that came their way every once in a while. Fans also had some access to slightly freer Eastern European press, including the popular East German youth bulletin Junge Velt.

However, despite a dearth of information about the Fab Four, songs by the legendary group were only occasionally included in the musical collections released by the Soviet Union’s one and only record company, Melodia. Soviet fans heard the Beatles song “Girl” for the first time in 1967, and, in 1972, they were treated to “Let It Be.”

In total, more than 20 Beatles songs were released in the Soviet Union, all in violation of the band’s copyright. Soviet music-lovers who knew the original names of the songs in English were greatly amused by the Soviet-era translation of “Hard Day’s Night” (Vecher trudnogo dnya): it sounded like the would-be name of a Soviet television show.

In 1988, Paul McCartney gave his Soviet fans a magnificent present. Especially for them, he put together an official album of Beatles songs called “Back in the USSR.” Half a million copies were issued, making it the most widely distributed album by any foreign musician in the Soviet Union.

Video by Paul McCartney Music / YouTube

McCartney’s album sold out almost instantly and became one of the most valuable records amongst Soviet music-lovers. Prices for the album on the black market rose as high as 100 rubles ($3). This means a lot, considering that the average salary at that time was 150 rubles ($5) a month. Across the border, this same album, which was released only in the Soviet Union, was valued at between $100 and $200. The cover of the album bore a quote from McCartney: “In releasing this record made especially and exclusively for the USSR, I am extending a hand of peace and friendship to the Soviet people.”

McCartney, as well as left-wing Lennon, could have “extended a hand to the Soviet people” much earlier, according to Russian politician Aleksei Mitrofanov. There’s some truth to this opinion: the old guard in the Kremlin never realized how much the Beatles had done for the prestige of the Soviet Union in late August 1968. When Paul McCartney wrote “Back in the USSR,” the song had many good things to say about a country that had just invaded Czechoslovakia and earned the displeasure of the entire world.

In the Soviet Union, despite the song “Back in the USSR,” the Beatles received no special treatment. There were plenty of disparaging voices and reviews in the Soviet press that preferred to refer to the Beatles as the “Bugs.” Even the venerable Soviet composer Nikita Bogoslovsky joined the chorus of criticism. “I am ready to bet you that, 18 months from now, there will be a new group with even more idiotic haircuts and even weirder voices, and all the fuss will die down,” said the composer.

“At the time, it was thought that the direction in which the Beatles were headed did not fit in with the accepted ideology,” Russian President Vladimir Putin told Sir Paul McCartney at a 2003 meeting in the Kremlin.

It seems that only yesterday the Beatles were off-limits to Soviet leaders who, afraid of the “noxious influence” of these long-haired boys, kept a close eye on the haircuts sported by semi-tolerated Soviet bands. Today in Russia, the generation that grew up on Beatles songs is now in power. Fans of the band include Chief of the Presidential Administration Sergei Ivanov, who attended McCartney’s 2003 concert on Red Square.

Despite the shortsightedness of Soviet leaders (who were, in truth, as afraid of left-wing Westerners as they were of right-wing ones), there was a popular legend in the Soviet Union and in post-Soviet Russia that the Beatles had, in fact, played in the Soviet Union at a closed-to-the-public government concert.

Although there is no documented evidence to confirm this legend, music experts later hypothesized that this concert may well have been performed by one of the Soviet music groups that imitated the Beatles – for instance, Blitz from the Soviet republic of Georgia.

“Of course, this was fake Beatles, but after all we all grew up on fake sausage, played on fake guitars, studied fake history, bought records by fake singers with our fake money, and listened to the fake leader of our government on television… So fake Beatles was far from the worst of it,” said Aleksei Rybin, who once attended a Blitz concert. “The main thing was how well they sang Beatles songs in English: this Georgian group had worked long and hard on its pronunciation when rehearsing such hits as ‘Yesterday’ and ‘Hard Day’s Night’.”

The most sophisticated Soviet schoolchildren studied English, not so much to learn tedious texts about the struggles of Communists, but so as to understand what the Beatles were singing about. Economist and politician Grigory Yavlinsky was once one of those schoolchildren: “When, in the 1980s, it became possible to go abroad, I found there was almost no barrier to communication. Then it turned out that people of my generation all shared a ‘fundamental code,’ a single language: it was the decade spent with the Beatles.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox