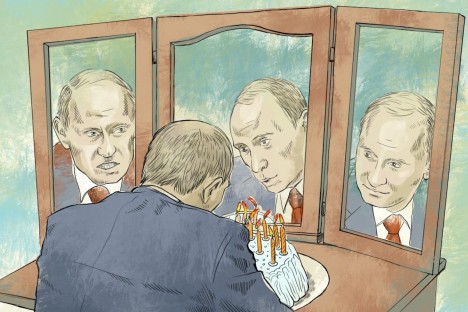

Putin struggles to resolve current international problems

Click to enlarge the image. Drawing by Nstalya Mikhaylenko.

On his 60th birthday, Russian President Vladimir Putin remained one of the most influential politicians on the planet – as idolized as he is demonized. In Russia and abroad, Putin is gradually turning into a brand, as a concept or political product that means different things to different people.

Two years ago, Forbes magazine named Putin second on their list of the most influential politicians in the world – after Barack Obama, but ahead of China’s leader Hu Jintao. Of course, this is nonsense. Statistics leave very little doubt that the leader of China wields more influence on the international stage than does Russia’s president.

Related:

Putin 2.0: Insight from experts

Putin takes on international politics

Still, Putin’s presence and personality are strong enough for him to be seen separately from the country he leads. This is not thanks to anything that Putin has done or has not done; the Russian President has simply become a reflection of the gloomy transitive state in which the whole international system now finds itself.

Putin came to power with a promise of stability for Russia. His ascendance came at the time when the world, which had just begun celebrating the end of the Cold War, stood on the brink of an economic meltdown. Uncertainty grew, while institutional structures that had been taken for granted collapsed before our very eyes.

The feverish attempts of the West to prop up the global system only led the latter to its breaking point. United and “globalized” as never before, the consequences of one actors’ mistakes were felt everywhere. As such, the stabilization process going on inside Russia was out of keeping with the situation in the outside world. In other words, Putin stood for the polar opposite of the general trend.

Many people see Putin as the “archetypal” enemy of progress, a symbol of outmoded ideas and old-fashioned approaches. It would seem that the Russian president himself exists in a state of permanent, barely-disguised rage against the policy of other global powers that appear to intentionally stir up the international situation and shake the very foundations that struggle to keep it together.

Putin’s articles and public speeches are often based on the premise that the world is a dangerous and unpredictable place, in which the actions of the world’s most powerful countries only exacerbate these threats. This seems obvious, but, for some reason, the consequences of wars, invasions, interventions and reforms have come back to bite those who initiated them. The past ten years yield numerous examples of this – from Iraq to Libya.

Putin is not alone in his refusal to accept this state of affairs, yet he is the one known as the vanguard of resistance. This is primarily because Russia, despite its decline after the collapse of the Soviet Union, remains a highly dynamic country that does not attempt to hide its ambitions.

Furthermore, Russia’s nuclear and raw-material potentials mean that the country’s opinion cannot be ignored. Finally, in terms of the president’s specific character, Putin simply stands out from the other politicians for his frankness and straight talk.

Many political observers are convinced that Putin is a wily strategist, guided by a “big plan” that involves expansion, restoration of an empire, consolidation of the power vertical and, ultimately, a return to the Soviet Union. This lends the Russian president an additional image of pure power. Putin, however, is unlikely to put much stock in the concept of strategy – at least not consciously.

The president of Russia is a reactionary in the sense that he likes to react: his favorite political “tactic” is to respond to a stimulus. In this way, he knows the source and character of the challenge and can act quickly, effectively and without error.

The ever more turbulent situation outside of Russia worries Putin, mainly because it resonates with the internal manifestations of instability and turns them into louder and more insistent threats. Like many Russian conservatives before him, Putin is always claiming the country needs time to secure stable, sustainable, managed development. In other words, it is still too soon to give in to the demands of those fighting for liberal democracy.

Over these years, we have resurrected the carcass of the state that was destroyed after the collapse of the Soviet Union, and now we need to strengthen it. We still need time for dostroika ( “further construction”), Putin said at a pre-election meeting in February. His choice of words is interesting – he deliberately declined from using the phrase perestroika (literally “re-building”) and went for dostroika instead.

Many Russians see the term perestroika,which was coined by Mikhail Gorbachev, as a synonym for catastrophe. The Russians words come from the same root, but dostroika means a careful completion of construction, with the sense that there is still a work in progress.

Putin understands that the protests that met his return to power were based on more than just provocation from the West. These protests signified changes happening within Russian society. But Putin is still convinced that the protesters are wrong, no matter how much they believe in what they are doing – the time is just not right for it yet. Russia needs to take a bit more time, and, for now, to carry on slowly constructing and polishing...

Over and over, Russian history has shown that conservatives never find the extra time they so desire. Something has always happened, and their efforts, even if they are correct and constructive, turn to dust under the insistent march of time and change. Changes are certainly not always for the best, but no one is thinking about this when they are happening.

Having returned to his position as head of state, Putin has not delivered magical solutions to the problems that have arisen; but he returned with his own characteristic sense for what is dangerous, for the fragility of everything around him.

It is hard to accuse Putin of having no strategy – no one seems to have one these days. In our unpredictable world, there does not seem to be any point to having one. The situation in Europe shows that structures that appear well-thought-out and stable can tumble like a house of cards. As a conservative and a realist, Putin is soberly evaluating what has happened, but he cannot find answers to the mounting problems we face.

Fedor Lukyanov is the editor-in-chief of Russia in Global Affairs magazine.

This opinion is first published in Russian in the Ogoniok magazine.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox