|

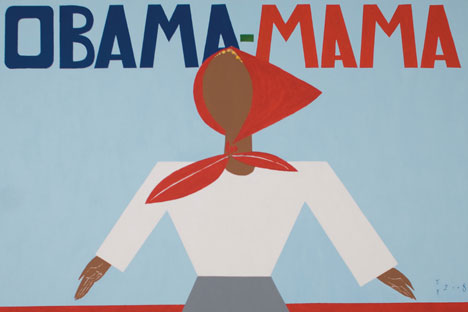

| Obama-Mama courtesy of Pavel Pepperstein collection. |

This is a dramatic time for Russian art. Nineteenth and early-twentieth century works continue to break auction house records while more recent artists, encouraged by a growing network of galleries, are reaching wider and more appreciative audiences. So the publication of a massive survey in English of Russian contemporary art should not be surprising. The question might rather be why it took so long. Editor Hossein Amirsadeghi agrees: “This was a book crying out to be made.” The resulting monumental, fully illustrated tome, entitled “Frozen Dreams,” (Thames and Hudson, edited by Amirsadeghi and Joanna Vickery) is an impressive achievement. Wrestling the artistic output of the world’s largest country into 300 accessible pages must have been like trying to pour the ocean into an elegant wine bottle, but the editors have produced an extraordinary book. The scope for omission, conflation and confusion is as huge as the project itself, and yet this survey gives an admirable overview (580 images from 100 Russian artists) of the strength and diversity of Russian art today.

The whole point of art?

|

| Cover of the book "Frozen Dreams." |

Eric Bulatov’s 1973 painting, “Welcome,” with its ironically glowing view of the lavish fountains and pavilions in Moscow’s Soviet exhibition grounds has a two page spread at the start. Bulatov’s later satires on propaganda continue to explore the tension between social reality and the official vision of it.

There are disturbing photographic montages by the AES+F collective, featuring children with weapons or images from classical myth or sci-fi in a hyper-real setting. Restless émigré, Pavel Pepperstein, is represented alongside his Moscow conceptualist father, Victor Pivovarov; Pepperstein’s symbolic drawings suggest influences as disparate as advertising posters and fairy tales; his recent works include a utopian protest against the destruction of “our beautiful cities.”

The variety of styles and media is overwhelming. The artists are listed in alphabetical order, rather than according to theme or chronology, which encourages the reader to appreciate them individually.

Maxim Kantor, one of the more figurative painters, with an arresting and visionary use of color reminiscent of Van Gogh, explains that he was never part of any artistic movement, being convinced that even if the subject matter is tragic, “a painting must be beautiful. That is the whole point of art.”

A place in global culture

Three introductory essays give the book an authoritative context. Expert, critic and researcher, Ekaterina Bobrinskaia, who published a book last year on “Unofficial Art” presents a conscientious overview of twentieth century developments. Alexandra Danilova, who curated the 2010 “Field of Action” exhibition of Moscow conceptualists discusses postwar art and politics. She examines local and global trends, including resurgent neoclassicism, postmodern pastiche, photographic and multimedia works.

Finally, American art critic, Eleanor Heartney, looks at western perspectives on modern Russian art and challenges some of the accepted narratives: “Because images, ideas and even words have different meanings on either side of the former Iron Curtain, much can get lost in translation.” She considers the roles of faith and of feminism and how far the “international Esperanto of postmodernism” is bringing artistic communities together. The book ends with a useful timeline that runs from the death of Stalin in 1953 to last year’s relocation of the Garage Centre for Contemporary Culture in Gorky Park.

Too intellectual?

|

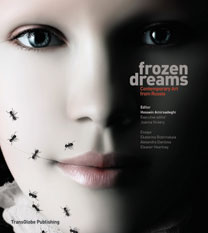

| I love Moscow, from the Cycle AT THE STOP (Semyon Faibisovich). Courtesy Regina Gallery. |

Authoritative cultural surveys run the risk of limiting the very field they set out to describe. From a layperson and outsider’s standpoint, there is no easy way of knowing who or what is missing from this list. There seems to be a bias against straightforward figurative art, however accomplished. Works by avant-garde and conceptual artists, from the Blue Rose exhibition of 1907 to the present day, are championed. There is an unspoken understanding that during the Soviet era the work of dissident artists, as opposed to the officially sanctioned socialist realism, was the only “true” art. Thus, the Moscow conceptualist school, with their archives and performances, are seen as crucial, although their work is particularly dependent on its context. The descriptions of artists are generally reader-friendly, but there are moments when deconstructionist jargon intervenes; the work of Sergei Bugaev, for instance, (who calls himself “Afrika”) tests the “inability to connect signifier and signified.”

The French collector and publisher Pierre-Christian Brochet observes that many curators “try to be too intellectual.” Likewise, the owners of the Triumph Gallery insist that “art must be beautiful. Interpretation comes later.” One of them, Emelyan Zakharov, compares the current educational system in the West, where people “are taught how to think and question” at the expense of rigorous, academic and skills-based training. In Russia, he says, “We have the opposite problem.”

Too centralized?

From more than thirty galleries and collectors featured, there are relatively few from outside Moscow; most of the artists listed are based there too. Of course, the lure of any capital city is powerful and the book includes comments by gallery-owners on this issue. Aslan Chekhoev, who founded St Petersburg’s Novy Museum in 2010, is concerned that the migration of strong artists to Moscow is leaving a cultural void in the provinces. But Marat Guelman, a successful critic and collector with his own gallery in Moscow has discovered hope and inspiration in regional projects. Hired as director of the pioneering Perm Museum of Modern Art when it opened in 2008, he believes that, despite the challenges involved, “a phenomenon is being created in Perm that will pull all of Russian art up to international level.”

Bound together in exploration

|

| Untitled, from series Persian Miniatures (Ajdan Salakhova gallery). Source: Press Photo. |

“Frozen Dreams” also offers a unique global perspective; it features foreign collectors, like the late Norton Dodge, who helped to keep Russian art alive in the Soviet era, as well as galleries outside Russia. Expatriate artists also provide an interesting commentary on the meeting of cultures. Leonid Sokov, for instance, has created contrasting iconic bronze figures of Lenin and Giacometti’s walking man. His poignantly symbolic work “My Subway Map” consists of plans for the Moscow metro and the New York subway bolted together with cast iron. Aidan Salakhova, co-founder of one of Russia’s first private commercial galleries back in 1989, comments on the limited perspective among westerners for whom “Russian art is either a matryoshka doll or a black square”; but several other gallery owners, like Elena Selina of XL, observe that Western markets have been the most receptive. Heartney’s conclusion – and perhaps prophecy – on current artistic developments suggests a cooperative future: “Where once the West and Russia offered distorted reflections of each other, today, increasingly, they are bound together in an exploration of the complexities of the twenty-first century world.”

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox