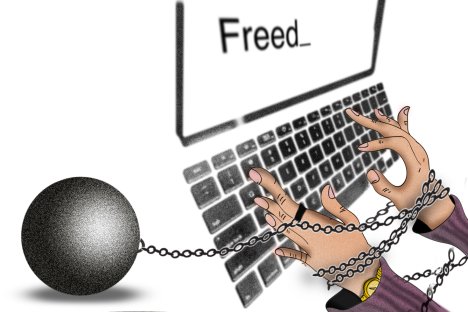

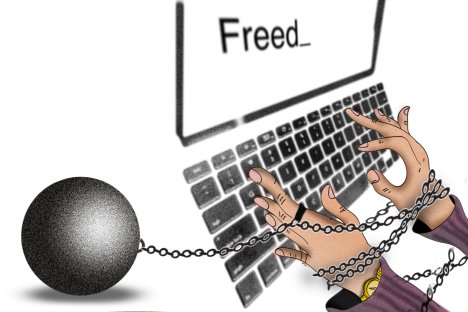

Free speech in peril

Click to enlarge. Drawing by Niyaz Karim.

In 2003, Russia witnessed a court consider criminal prosecution of curators when a museum displayed images that were deemed offensive by some priests and members of of the Russian Orthodox Church. However, when a court in Grozny, the capital of the autonomous republic of Chechnya, decided to ban the controversial “Innocence of Muslims” video from distribution in Russia, it made history.

Should this decision be upheld by the judicial system, it will become the first official act of outright religiously motivated censorship in the post-communist history of Russia. It will also have consequences going far beyond the mere issue of a half-baked home video.

The official pretext for the ban is that the film is “extremist” – a punishable offense under Russian law. The penal code clause 282, dealing with extremism, was written as a safeguard against Islamist terrorists, Nazi skinheads and their ilk. It is now being widely used to suppress dissent and limit free speech.

The fact that it was the Chechen court that took action against “Innocence of Muslims” confirmed in the eyes of many that Chechnya’s role as a self-appointed enforcer of Islamic orthodoxy across Russia is tacitly recognized by the Kremlin. The region, headed by a former guerilla-fighter-turned-Kremlin-loyalist Ramzan Kadyrov, enjoys exclusive status in Russia.

Many say the country’s laws there do not apply (or at least, are not observed in full). Stories of women in Chechnya being forced to wear headscarves or pray; the ban on alcohol sales and other tales keep surfacing at regular intervals. The gradual fracturing of federal legislation and introduction of “Sharia by stealth” bodes badly for the country’s unity.

The “Innocence of Muslims” ruling places a question mark over the freedoms guaranteed by the Russian Constitution and the international human rights convention Russia has also signed, which includes freedom of information and freedom of artistic expression, including the principle of the “freedom to offend.”

The State Duma already decided to amend the penal code to include punishment, ranging from heavy fines to jail terms for “offending the feelings of believers.” It is an all-encompassing and deliberately vague term that lawmakers deliberately keep that way.

In the wake of the scandalous and controversial Pussy Riot “blasphemy” trial this summer, the Kremlin intends to clamp down on free speech wherever possible. It also views the majority of believers as a bedrock of support against pro-democracy activism. In exchange the authorities promise to ensure that religious belief will de facto be off limits for criticism in Russia.

The religious revival in Russia is only twenty-five years old. For many their faith has replaced the communist ideology of the past. There is practically no tradition of reasoned discourse and coexistence between believers, agnostics, and atheists. For many Russians, Christianity, Islam or (increasingly) militant secularism are not causes to be argued for but imperatives to be executed in real life – and woe to those who resist!

In this divisive atmosphere alliances of convenience are made or broken. While Muslim clerics sided with the Russian Orthodox Church in demanding that Pussy Riot receive strict punishment for their blasphemy, the Church itself views growing numbers of Muslims in Russia and their active proselytizing as a challenge at best, and a potential threat at worst.

Orthodox activists organize campaigns to protest the construction of new mosques in bedroom districts of Russian cities, and Muslims complain they are not well represented in state institutions.

This situation suits the Kremlin well, as it is then the ultimate arbiter in all disputes between different faiths and secular society, as well as among the religious communities themselves. In the name of stability, the state can now restrict free speech – pretty much on any subject.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox