Tackling global contradictions

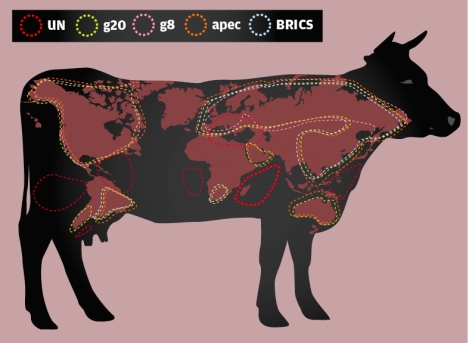

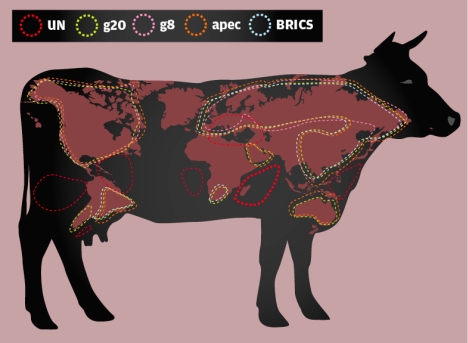

Click to enlarge the image. Drawing by Alena Repkina.

The problems that determine the present and future of countries and peoples are, for the most part, global in character: climate change, the increasing shortage of fresh water, rising food prices and the increasing relative shortage of raw materials and energy.

Confronted with the global world, societies have fell back on the habitual instrument and buttress of the nation state, which only recently was declared moribund. We are witnessing a partial re-nationalization of world politics.

“The contradiction of contradictions” is that, between the globalization of the world and the de-globalization of its management, a governance vacuum is being created.

The U.N. has long since become a body that is good for dialogue, but of little use in resolving major global problems. Its Security Council is weakened by its diminishing legitimacy. Moreover, even on core issues of crisis management and prevention, the Security Council is frequently bypassed or has its mandates distorted.

The majority of other organizations created after World War II are experiencing similar trends. The G-7 of leading industrialized countries, which was created in the 1970s in response to the energy and economic crises of the time, played a positive role in coordinating economic policies. By the beginning of the current millennium, however, just as Russia was becoming a full-fledged member after nearly a decade of waiting, the G-8’s influence was rapidly diminishing.

In the 2000s, the emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and, more recently, South Africa set up BRICS. This organization, contrary to numerous negative forecasts by Western experts who did not want it to succeed, is developing. The political weight of its members is increasing; but BRICS has so far done next to nothing to deal with concrete problems.

In terms of filling the governance vacuum, much greater hopes are pinned on the G-20 – an informal organization that brings together the 20 largest economies in the world. Created in the late 1990s, the G-20 turned into a summit of heads of state at the start of the 2008 global economic crisis. It played an indisputably positive role in preventing panic and, consequently, the collapse of global economy.

Nonetheless, the organization failed to come up with a common policy. There is a growing sense that the G-20 is going the way of the G-8, with more and more talk and less and less walk.

The G-20, like the G-8, has not created a permanent secretariat or a bureaucracy interested in developing the organization or demonstrating its effectiveness. Without the weight of bureaucracy, institutions cannot survive in this fast-changing world.

Though important in and of itself, the question of the future of leading organizations called upon to fill the “governance vacuum” is particularly relevant to Russia. Over the course of 2013-2014, Moscow will host and chair the BRICS, G-8 and G-20 summits.

This is a unique opportunity to at least increase the country’s international and political weight. At most, it is a chance to help fill the deepening global “governance vacuum.”

It is doubtful that the BRICS summit will deliver a breakthrough. It is too young, and, in many ways, it is still a virtual entity.

The G-8 is obviously in crisis and in danger of fading away. But there is potential for re-activating it to the benefit of all. Russia is already prepared to propose ways to make it more effective.

The G-8 was created as a Western club to discuss and coordinate economic policy. For some time now, it has been drifting toward discussing geopolitics and security issues. Perhaps its geopolitical specialization should be consolidated.

To be sure, these and other global issues cannot be discussed without the two new great powers – China and India. They should be invited as full-fledged members.

A similar challenge is to develop the G-20 or, at least, prevent it from petering out. This should be done by extending its mandate to include, for example, the freshwater supply deficit, which is set to become the most conflict-generating economic and political issue of the future. Russia, being one of the richest countries in water resources, could initiate development of an international strategy for tackling this problem.

However, the key to the modernization of the G-20 is not to add important issues to its agenda. The organization must be institutionalized by replacing its currently unwieldy and inefficient management system with a permanent secretariat and a bureaucracy.

The global economy does not lend itself to being controlled at the national level – it is sliding into chaos and calls for systemic governance in the interests of all. Otherwise, the “contradiction of contradictions” might destroy the world without the aid of warfare, or, at least, it may derail global development.

Sergey

Karaganov is Dean of the World Economy and World Politics Faculty at the Higher

School of Economics. First published in Russian in Vedomosti.ru

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox