Russian architect debuts in London

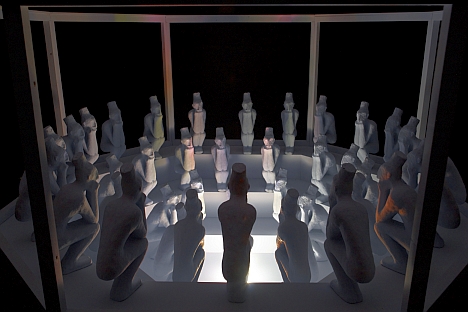

Alexander Brodsky's “Black Room,” presented at London's Calvert22 gallery, is a dark void, apart from a pale, flickering fire in the center of an octagonal model arena filled with identical, crouching figurines. Source: Calvert22 / Press Photo

An ice house on a frozen lake or a vodka pavilion made of recycled wooden window frames; a restaurant balanced on subtly-sloping stilts above the water; an abandoned subway station that becomes a canal in Venice, or a clay city which is submerged in oil.

Alexander Brodsky’s architectural projects and installations are both varied and visionary. Famous in 1980s Russia as a “paper architect” whose imaginative etchings broke free from the standard Soviet blueprint, he moved on to produce site-specific exhibitions and actual buildings. He talked about his work in October at London’s Courtauld Institute of Art.

Brodsky’s first solo U.K. exhibition opened earlier this month. The architect has installed two contrasting spaces inside the Calvert22 gallery. In the bright, curtained “White Room”, a long row of miniature beds are reflected in mirrors at either end. The “Black Room” is a dark void, apart from a pale, flickering fire in the center of an octagonal model arena filled with identical, crouching figurines.

Brodsky insists that there is no defining story behind the work at Calvert 22, which is based on his own responses to the space, and that the viewer needs to provide their own narrative. Antonia Seroffa, who works at the gallery, observes how visitors in the dark room tend to crowd around the edges and lean towards the fire, mimicking the figures. The white room, with its distortions of space, “makes me think of a madhouse or asylum,” she said.

Alexander Brodsky's "White Room," presented at the Calvert22 gallery. Source: Calvert22 / Press Photo

Painter, Rebecca Hathaway, who was visiting the new exhibition last week, also found the use of space interesting “because there were no square corners at all; all the angles were deliberately slightly off so that it was playing with your spatial awareness.” Downstairs, there are recent sketches of birds and buildings and a characteristically crumbling, skew-angled factory made from unfired clay.

Born in Moscow in 1955, Brodsky has been a life-long Muscovite. He studied at Moscow’s Institute of Architecture in the early 1970s, where he began three decades of collaboration with his fellow student Ilya Utkin.

“We wanted to combine literature and art,” Brodsky said of their Piranesi-inspired early etchings, wonderfully elaborate, incorporating text and numerous, detailed subsidiary drawings.

Of one of them, “Crystal Palace”, Brodsky said: “this was a symbolic project. It looks like a city from a distance, but when you get closer there is nothing, just a series of glass sheets in the sand, no walls, no roof.”

The works that followed, many of them entries for Japanese architectural competitions, were similarly allegorical. A claustrophobic windowless, circular prison with a paradoxical view of the open sky; or a huge glass tower, empty except for a staircase from which the image of an individual was magnified and projected to the whole city. This one, Brodsky said, was “a symbol of the human ego – something that had to be built higher and higher.”

On the question of whether or not he thought of himself as a dissident, Brodsky said: “Of course we grew up in a really strange place. The lie was everywhere. It was impossible not to be some sort of dissident; it was just a matter of what kind of dissident you were.”

Some of Brodsky and Utkin’s paper works are playful, like the “Winnie the Pooh House”, a complicated octagonal tower with a spiral staircase, roof terrace and stargazing telescope, borrowing elements from children’s stories. A more macabre fantasy informs the “Columbarium Habitable” which is about the disappearance of old buildings in a modern city.

Alexander Brodsky's exhibition at London's Calvert22 Gallery. Source: Press Photo

“We saw it every day in Moscow and it was very painful,” said Brodsky. In the fairy tale illustration old buildings can be relocated to a concrete shelf, like those on which urns of ashes are stored in a Russian cemetery, or destroyed; a wrecking ball swings in the middle of the picture. “It’s a sad story,” he said. “How can we preserve these buildings?”

This theme recurs in Brodsky’s work, most graphically in a piece called “Coma” for the Moscow’s Guelman Gallery. A model city on a surgeon’s table slowly drowns in crude oil. Brodsky set up his own architectural practice in Moscow in 2000 and won the European “Best Artist” award at the Milan Triennale the following year.

Although it is a modest building, Brodsky is proud of his first commission, a wooden restaurant called “95 degrees” that he built over the Klyazma Reservoir near Moscow in 2002.

“For me it was a very important moment,” he said. “I decided to make all the verticals at an angle to the water. It was all made of wood, on a low budget. It was never intended to be permanent, but it is still there ten years later.”

The Pavilion for Vodka Ceremonies, also built as a temporary structure on the same reservoir, is: “all made of old windows saved from a beautiful, old factory that was demolished in the center of the city. I painted everything white myself and it became a translucent, beautiful thing with sunlight coming through.” The “Ice Bar” was even more ephemeral, made simply from frozen lake water on a wooden frame and “in spring the whole thing disappeared.”

Alexander Brodsky's Ice Pavilion. Source: Yuri Palmin / Press Photo

Numerous collections worldwide have purchased Brodsky’s artworks, including Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art and The Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 2012, he won the Kandinsky Prize, the biggest independent award in Russian contemporary art, with an installation called “The Road.”

Modeled on a third class carriage in a Russian sleeper train, with its three layers of bunks and flimsy curtains and distinctive tea-glasses, it evoked – like the “White Room” ideas of sleep and dreaming. The austere space also represented the collision of the urge towards freedom and escape with the confining realities of communal travel.

Brodsky often returns to ideas of the past, of respect for the historical environment and the natural world. It’s hard for some critics to accept that classical columns or old door frames can be innovative.

New York architect and theorist, Srdjan Weiss justifies Brodsky’s neo-traditionalism in an essay for the catalogue that accompanies “White Room/Black Room,” describing Brodsky’s use of the antique as “a new form of modernization” and a radical “revitalization of possibilities that were forgone in recent history.” From this perspective, Brodsky’s nostalgic visions are dreams of a better future.

“White Room/Black Room” runs at the Calvert22 gallery until Nov. 25.

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox