Leo Tolstoy vs. the world: 3 harsh holy wars in which the famed Russian writer participated

There were many things that powerful Leo Tolstoy just couldn't stand - and he never was too shy to talk about it.

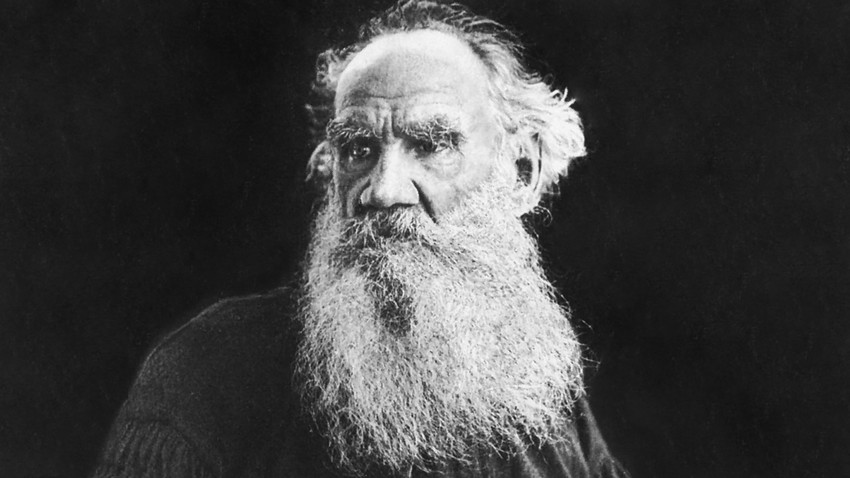

Public domainIn 1884,

Surely that was only part of the truth. Back in the 1880s, Tolstoy who had already written his masterpieces War and Peace and Anna Karenina, now concentrated on philosophical writings and was extremely popular in Russia with hundreds of people adoring him (starting from the emperor Alexander III who called him “my Tolstoy”).

Nevertheless, he sparked serious disputes in society as his views were radical and contradicted the official line of both government and church. Here are three holy wars that Leo Tolstoy, Russian “king of controversy”, took part in.

Tolstoy vs. the state

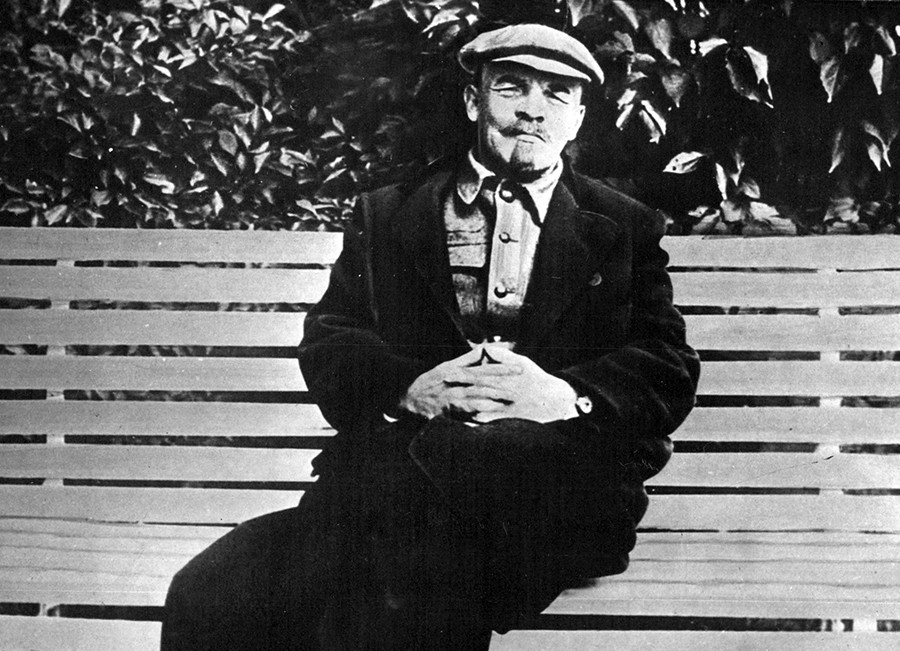

Vladimir Lenin, the greatest Russian revolutionary, respected Tolstoy for his harsh criticism of the Russian Empire. Nevertheless, their views differed with Tolstoy being a pacifist opposing any violence.

ZUMA Press/Global Look PressIn other words, the author was a self-consistent anarchist. As philologist Andrei Zorin pointed out, since Tolstoy’s childhood the whole idea of suppressing the individual (and power, even balanced and limited, does that) was violent and unacceptable for him.

His humanism opposed any powers-that-be, thus making him a dangerous liberal for those in charge. Tolstoy believed that climbing to the top of the society required cunning and dirty tricks, so it’s the worst people who rule the world.

At the same time, Tolstoy was never a revolutionary, as he did not believe in violent means. Although Vladimir Lenin, the future leader of the USSR, called Tolstoy “the mirror of the Russian revolution” for his description of deep contradictions in Russian society, he criticized the author for “incoherent” views and insufficient criticism of the government. Tolstoy didn’t care, preferring the spiritual to political life. But in this

Tolstoy vs. the Orthodox Church

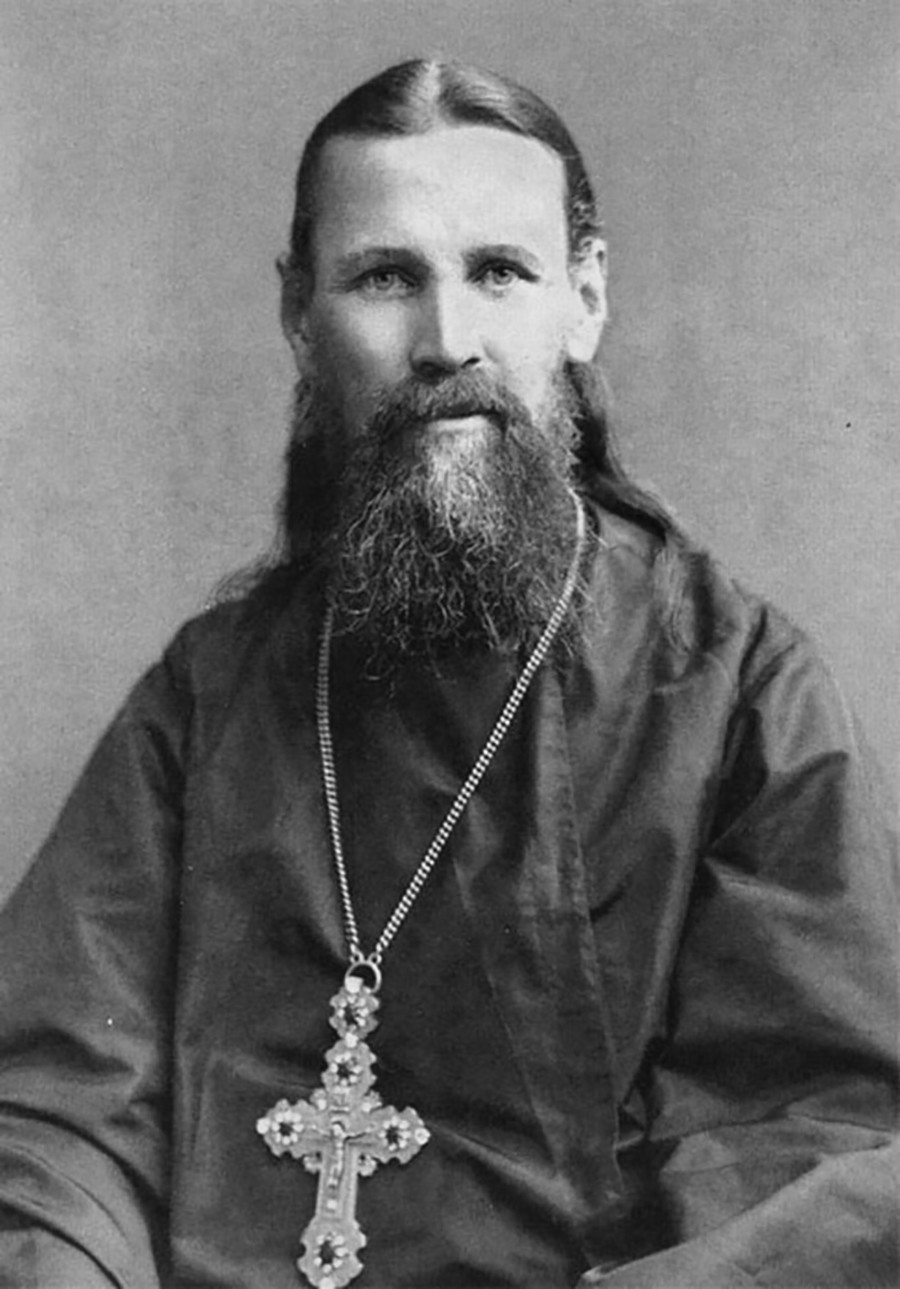

There was no love lost between Tolstoy and father John of Kronstadt, the famous Orthodox priest of his time. The latter even prayed for Tolstoy's death, which was not very Christian of him.

Public domainA believer all his life, from a certain point Tolstoy separated ways with the official Orthodoxy. Back in 1855 (in his twenties), he mentioned in his diary that his aim was to create a new religion – Christianity “purified” of mysticism. He and his supporters, believing in Christ and considering themselves Christians, called for focusing on living this life wisely and righteously, not waiting for the afterlife.

Tolstoy advocated strict moral norms implied by the Church but denied miracles. For example, for him Christ hadn’t resurrected after being crucified in Jerusalem: he was only a righteous man, not a Son of God. Such an approach, “Christianity with no wonders,” triggered outrage among church officials.

As it wasn’t enough, Tolstoy loved to criticize them harshly, calling Russian priests “self-confident but lost and poorly educated, dressing in silk and velvet.” To him, the Church corrupt with power and money, couldn’t be a moral authority and was only enslaving the peasants.

The Church leaders spared no criticism towards Tolstoy. Presbyter John of Kronstadt, one of the most popular Christian preachers of those days (later canonized), described Tolstoy like this: “He perverted all the sense of Christianity… he laughs at Church with Satan’s laughter.” He even prayed for Tolstoy’s death in 1908.

These anarcho-pacifist views along with his huge popularity and criticism of the priests led to Tolstoy's excommunication from the Russian Orthodox Church in 1901. Tolstoy recognized the act, agreeing that he disbelieved church dogmas and it would be hypocritical to be part of the Church. His excommunication remains valid in the Orthodox Church and no cross marks his grave.

Tolstoy vs. Shakespeare

William Shakespeare now is an indisputable genius of English literature. So he was back in the 19th century but it surely didn't bother Leo Tolstoy who slammed him harshly.

John Taylor, London’s National Portrait GalleryUnlike church and state, William Shakespeare, who also suffered from Tolstoy’s severe criticism couldn’t answer him for he had been dead since 1616. This, however, didn’t stop one of the greatest Russian writers from destroying (or, rather, trying to destroy) one of the most famous British.

“There is no real human talk in his plays,” Tolstoy wrote in a big essay dedicated to Shakespeare’s heritage. He also expressed that he felt “irresistible repulsion and tedium” while reading the plays, no matter what language he tried – Russian, English or even German.

It’s unlikely that Tolstoy thought that his criticism would undermine Shakespeare’s influence but he couldn’t help but write all in which he believed. Even while attacking plays of his fellow writer Anton Chekhov, count Tolstoy used Shakespeare as an example: “Anton Pavlovich, Shakespeare was a bad writer, and I consider your plays even worse.” History proved him wrong: both Chekhov and Shakespeare are still being staged throughout the world.

Want to know more about holy wars great Russian writers participated in? We have a special article on that – enjoy. Man, these people were always ready to fight.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox