Which rare Russian artifacts are stored in the U.S. Library of Congress?

Young Russian peasant women in front of traditional wooden house, in a rural area along the Sheksna River near the small town of Kirillov. Early color photograph from Russia, created by Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky as part of his work to document the Russian Empire from 1909 to 1915.

Prokudin-Gorsky Collection/Library of CongressThe Library of Congress contains more than 700,000 books, photographs and manuscripts in Russian and just as many in other Slavic languages dating from Ancient Russia to the present day. Many of these items are priceless. The library is the largest repository of Russian publications abroad.

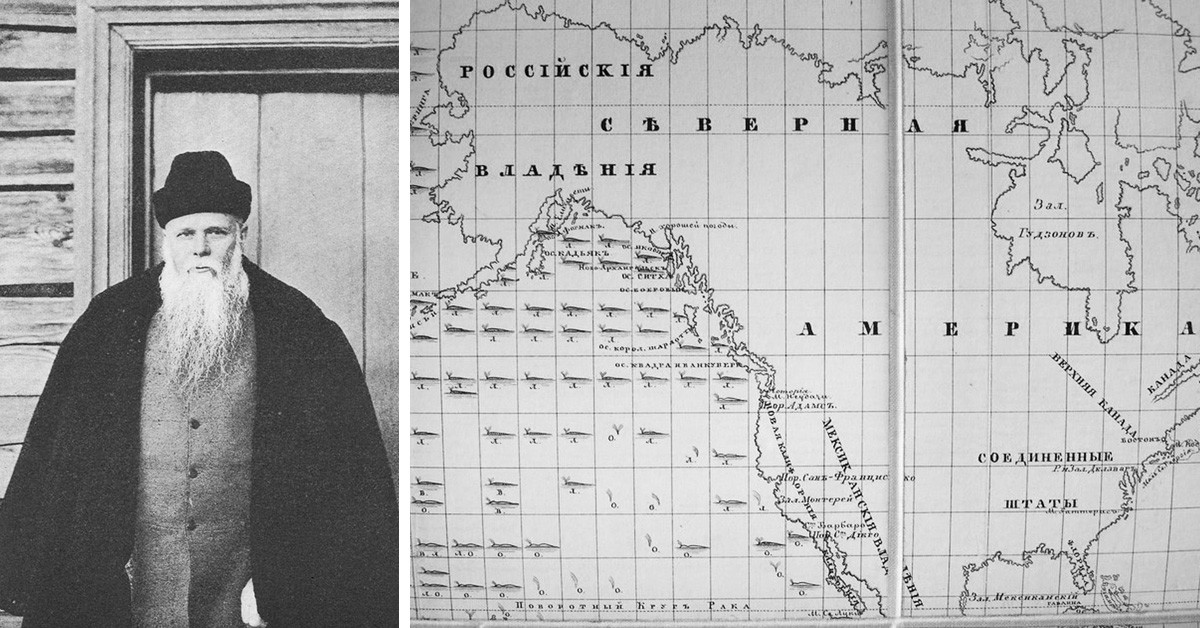

History of Russian America

Library of Congress.

AFPFirst and foremost, the Library of Congress houses documents related to the history of Russian America. Russian sailors founded several settlements in what is now the United States. These are located not only in Alaska, but also in Hawaii, California and around San Francisco. The library in Washington holds many documents relating to the period when these settlements were being established – from the official discovery of Alaska by Russians in 1732 to its sale in 1867. Among the documents, there is evidence of Russians traveling to Alaska in the 17th century. Their names did not survive, but it is known that they arrived on seven ships from Veliky Novgorod during the reign of Ivan the Terrible.

The Russian-American Company's reports about Russian settlements on new territories, along with the journals of Russian travelers to America, ended up in the Library of Congress from the collection of Gennady Yudin, a merchant from Krasnoyarsk. Yudin collected over 80,000 rare books, magazines and manuscripts from the 13-19th centuries, including first editions of works by Mikhail Lomonosov and Alexander Radishchev, as well as books covering the exploration of Siberia.

Yudin and detail of the map focusing on the vast Russian holdings in North America, 1852.

Yudin Collection/Rare Book and Special Collections Division/Library of CongressAt the beginning of the 20th century, Yudin’s business was on the verge of bankruptcy, and he decided to sell his collection. He even offered it to Emperor Nicholas II, but there were no buyers at the initial asking price of 250,000 rubles (around $120,000 at the time and equivalent to around $3.1 million today) or at the lowered price of 150,000 rubles. In the end, the Library of Congress bought Yudin's entire collection for 100,000 rubles, and in 1907 it wound up in the U.S. Some of the books have since been transferred to other American libraries and institutes.

In 1940, a library employee named Mikhail Vinokurov (a descendant of Russian Orthodox missionaries) traveled to Alaska on a three-month expedition and brought back tens of thousands of documents relating to the history of the Russian Orthodox Church in the United States. Of particular interest are the diaries of Russian priests from the mid-18th to the early 20th centuries, which give a detailed account of the Orthodox Church’s missionary work in the region.

Prokudin-Gorsky's photo archive

Lady's portrait.

Prokudin-Gorsky Collection/Library of CongressMuch of the legacy of the great Russian photographer Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky is now kept in the Library of Congress. In the early 20th century, he invented a new color photography technique and traveled to many cities throughout the Russian Empire, documenting everyday life. Thanks to his work, we know what Leo Tolstoy and Feodor Chaliapin looked like and what kind of clothing the inhabitants of different Russian regions wore. After the Bolshevik Revolution, Prokudin-Gorsky left Russia and continued working in Europe. He left behind more than 3,500 color photos, 2,300 of which ended up in Paris in the 1930s. Who and when managed to take them out of the Soviet Union remains a mystery, but they somehow ended up back in the hands of their author.

Some 400 negatives were subsequently lost, and after the photographer's death, his heirs sold the remaining 1,900 of his works to the U.S. These are mainly photo cards from different regions, including the Urals, the Caucasus, Turkestan, Volga, Oka, Little Russia and others. There is also a separate series dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812. The negatives have now been digitized and are available on the library website. In addition to the negatives, the collection contains more than 2,400 printed color photographs.

What happened to the 1,200 negatives that remained in the USSR is still not known. It is believed that among those missing there were photographs of the royal family taken by Prokudin-Gorsky on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty.

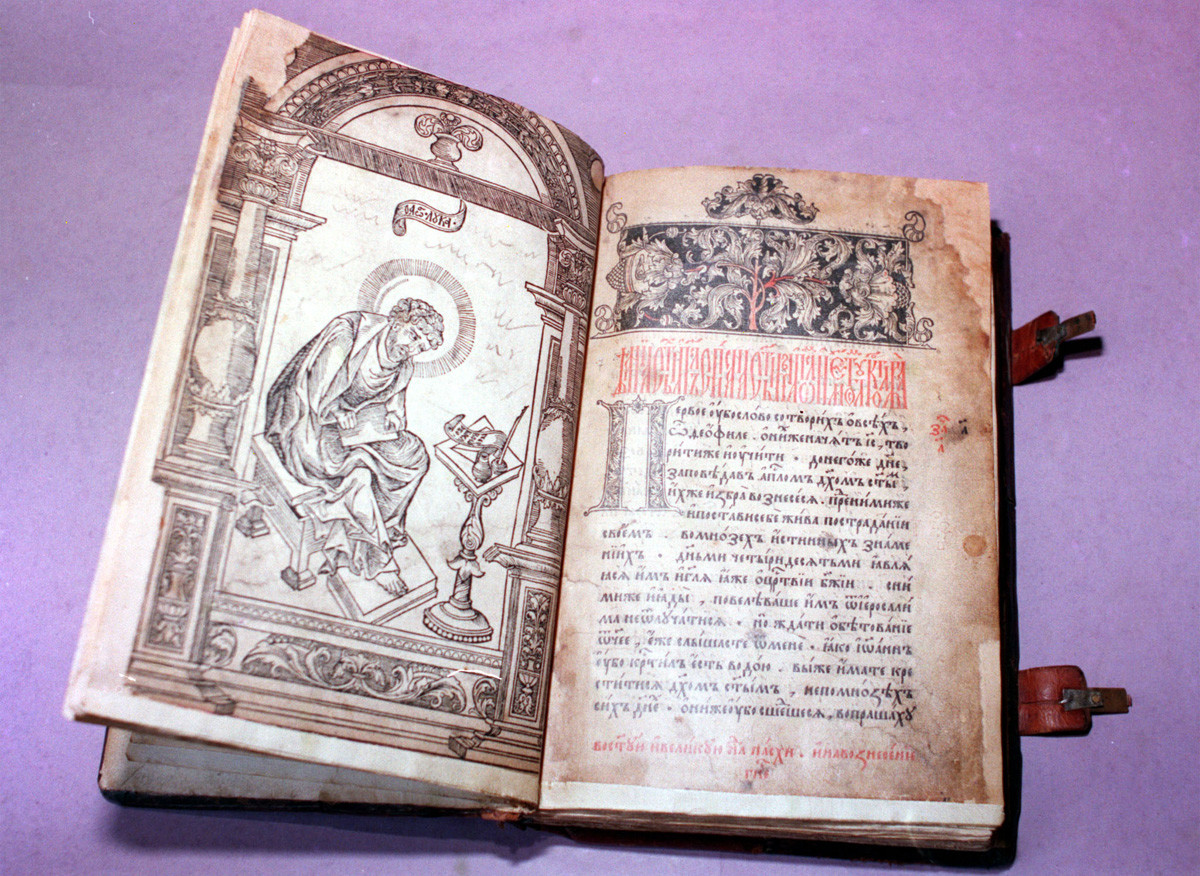

Russia's first printed books

Books of the Apostolos.

TASSThe library's department of rare editions contains around 4,000 Russian books from the 16-18th centuries that came from the Yudin collection. It also holds a copy of the 1564 Apostolos, the first printed Russian book that had a release date. This was a book for church services and contained part of The New Testament. Other rarities in the collection include the 1580 Ostrog Bible (also part of The New Testament) and the Sobornoye Ulozheniye legal code from 1649.

A workbook, 1787.

Yudin Collection/Rare Book and Special Collections Division/Library of CongressThe imperial family's library

Russian Imperial family Photo shows members of the Romanovs, the last imperial family of Russia including: seated (left to right) Maria, Queen Alexandra, Czar Nicholas II, Anastasia, Alexei (front), and standing (left to right), Olga and Tatiana. (Source: Flickr Commons project, 2010)

Library of CongressIn the 1930s, the Library of Congress acquired 2,600 items from the Romanovs' personal library from Israel Perlstein, a New York bookseller. In 1925, he visited the USSR and managed to negotiate the purchase of the imperial library, which was sitting in the basements of the Winter Palace. According to historians, Perlstein may have been used as an intermediary since the USSR and the U.S. did not have diplomatic relations at the time.

The collection included 18-19th century books in Russian, English, German, and French, many of which included handwritten notes by the emperor and members of his family. But the biggest treasure in the collection is the musical scores, including the first edition score of Glinka’s opera Ruslan and Lyudmila (1878) and Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Maid of Pskov (1894). The Romanovs' library also contained various state documents, such as the law on the abolition of serfdom, military laws and publications on civil law.

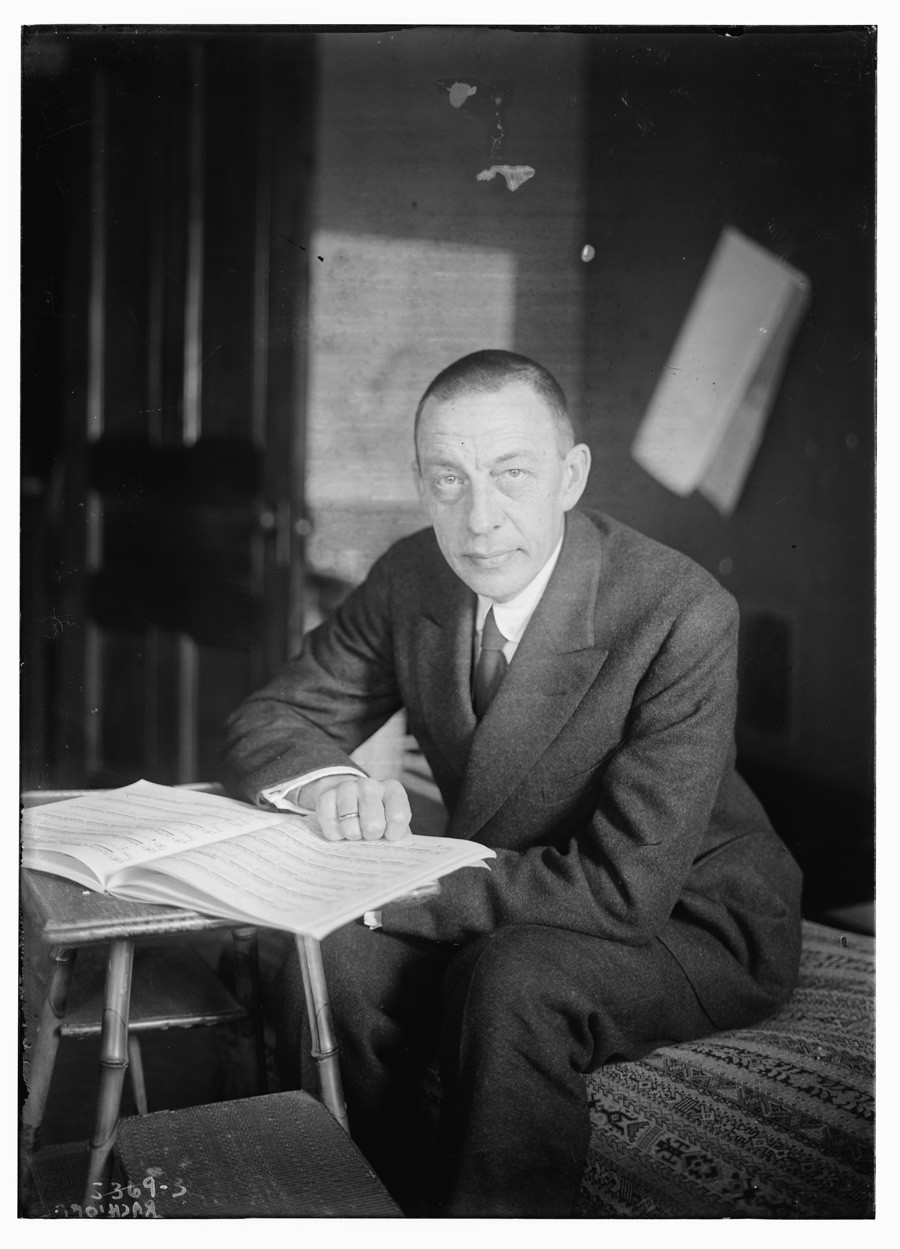

Sergei Rachmaninoff's archive

Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Library of CongressSergei Rachmaninoff, one of the greatest composers and musicians of the 20th century, left Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution and was buried in New York. He missed his homeland and even asked the Soviet Embassy to grant him Soviet citizenship, but he never received any reply. After his death, his widow offered to donate the composer's archive to the Glinka Museum in Moscow (the Russian national museum of music), but her offer went unanswered. She then decided to give the archive to the Library of Congress. Rachmaninoff's personal letters, photographs, awards, musical manuscripts and drafts – some 17,000 items in total – are now stored here.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox