Friends Savoska and Paramoshka are playing cards, while their underlings are watching them. Savoska loses and starts to tear his hair out in despair. The winner, Paramoshka, is taunting him, while his minion says, giving the loser a fig sign: “So, Savoska did not win a copper penny from Paramoshka.” The other underling is trying to cheer Savoska up: “Don’t cry, fool, son of a b*tch Savoska, Paramoshka will be beaten too.”

This humorous tale is typical of a Russian lubok, a medieval “comic strip”. Vivid colors, primitive drawings, captions that explain the plot - this is what a lubok is all about.

![Lubok ‘Savoska and Paramoshka’, 18th century. The caption says: “Paramoshka was playing cards with Savoska and Paramoshka won. Savoska looked into his purse and found a single kopeck there. [Paramoshka] began laughing at him, and he began to tear his hair out.”](https://mf.b37mrtl.ru/rbthmedia/images/2020.08/original/5f4cfa1c15e9f902337618f5.jpg)

Lubok ‘Savoska and Paramoshka’, 18th century. The caption says: “Paramoshka was playing cards with Savoska and Paramoshka won. Savoska looked into his purse and found a single kopeck there. [Paramoshka] began laughing at him, and he began to tear his hair out.”

Public domainThe lubok is a form of graphic art in which an artist creates a woodcut, makes prints from it, and then paints them by hand. The name comes from the word luba, meaning the inner part of linden bark, which was used to create the woodcut.

The mass production of popular prints was invented back in the 8th century in China, and, seven centuries later, engravings began to appear in Europe. Ironically, the technique reached Russia from the west, via Ukraine, Belarus and the Balkan countries. Xylography (woodcut) luboks were created in the printing house of the Kiev-Pechersk Lavra, one of the first monasteries in Kievan Rus’. Naturally, at the time, plots for the pictures came mainly from the Bible: funny luboks about Savoska and Paramoshka had not yet been thought of. The very first engraving is considered to be the icon of the Dormition of the Theotokos (1614-1624).

In Moscow, lubok prints began to spread from the tsar’s court in 1635, when 7-year-old Tsarevich Alexei Mikhailovich bought printed sheets on the Red Square. Later, lubok prints appeared among the boyars and soon spread among peasants, too.

‘Red Square in the second half of the 17th century’, A. Vasnetsov, 1925.

Appolinary VasnetsovIn the 17th century, the majority of lubok prints still belonged to the religious genre. Yet, in addition to creating life-like images of saints, artists in the cities began to produce printed sheets for amusement, which were sold among peasants. In 1653, after Nikon’s church reform, Old Believers and Nikonians began to create their own lubok prints. As a result, in 1674, Patriarch Joachim forbade depicting saints in lubok prints.

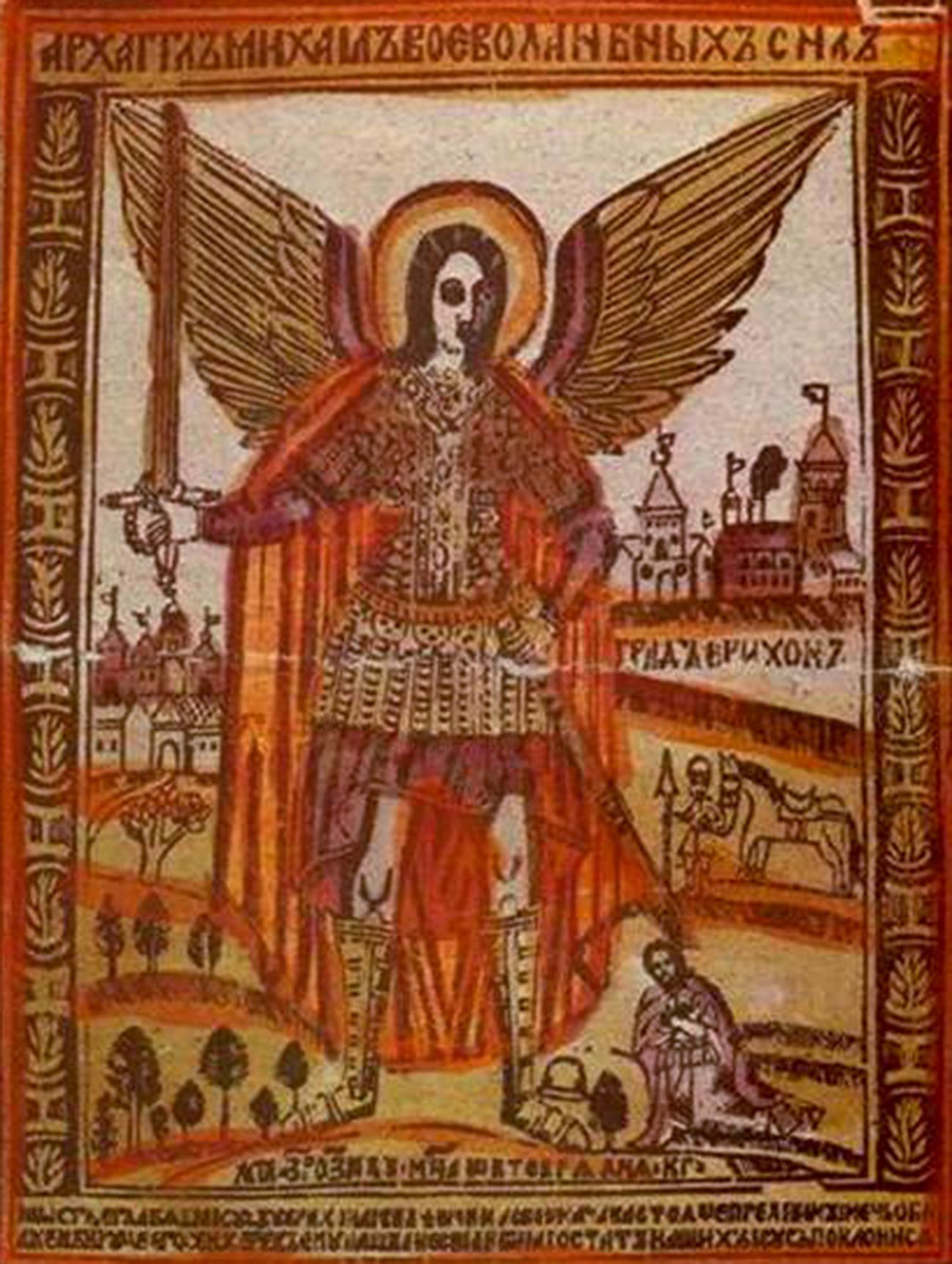

Lubok ‘Archangel Mikhail’, unknown author, 1668.

Public domainBy that time, Moscow already had its own workshops for the production of luboks, including Printing Sloboda at the corner of Sretensky and Rozhdestvensky boulevards. It employed woodcutters and printers, as well as craftsmen from the Kiev-Lviv printing school, for example, Vasily Koren, known for creating Russia’s first engraved Bible.

Lubok ‘Expulsion from Eden’, Vasily Koren, 17th century.

Public domainIn the late 17th and early 18th centuries, lubok prints depicting storylines from folk tales, epics and legends began to be sold at market stalls. The most famous folk characters depicted on lubok prints were Bova Korolevich and Yeruslan Lazarevich. They were known for their remarkable strength and courage in the face of hordes of enemies. However, their adventures were different.

The hero Yeruslan Lazarevich travels a lot and visits the Faraway Kingdom and Vakhrameyevo, where he marries his sweetheart Martha Vakhrameyeva. During his travels, he meets and becomes friends with the brave hero Ivan, and also battles with a three-headed serpent.

Lubok ‘Yeruslan Lazarevich’, 18th century.

Public domainUnlike Yeruslan, who goes traveling of his own accord, Bova Korolevich escapes from the palace andbecause of his evil mother Miritritsa and ends up in the kingdom of Zenzivy Andronovich. He falls in love with his daughter Druzhevna. There are many contenders for her hand, so Bova Korolevich goes into numerous battles and saves Druzhevna from the hands of King Markobrun. Luboks often depicted the battle between Bova Korolevich and Polkan, a creature with the upper body of a man and the lower body of a dog.

Lubok ‘Bova Korolevich and Polkan’, 19th century.

Public domainIn the 18th century, Peter the Great realized that lubok prints could work well for domestic propaganda purposes. That is why in 1711, he set up an engraving chamber, which employed the best lubok artists of the time. Already in 1724, the emperor issued a decree on the printing of luboks from copper plates.

This made artists’ work easier, since copper engravings were more expressive and precise than woodcuts. With copper plates, creating prints did not require quite so much effort: instead of a chisel, acids and needles were used, and defects could be corrected with the help of a special varnish.

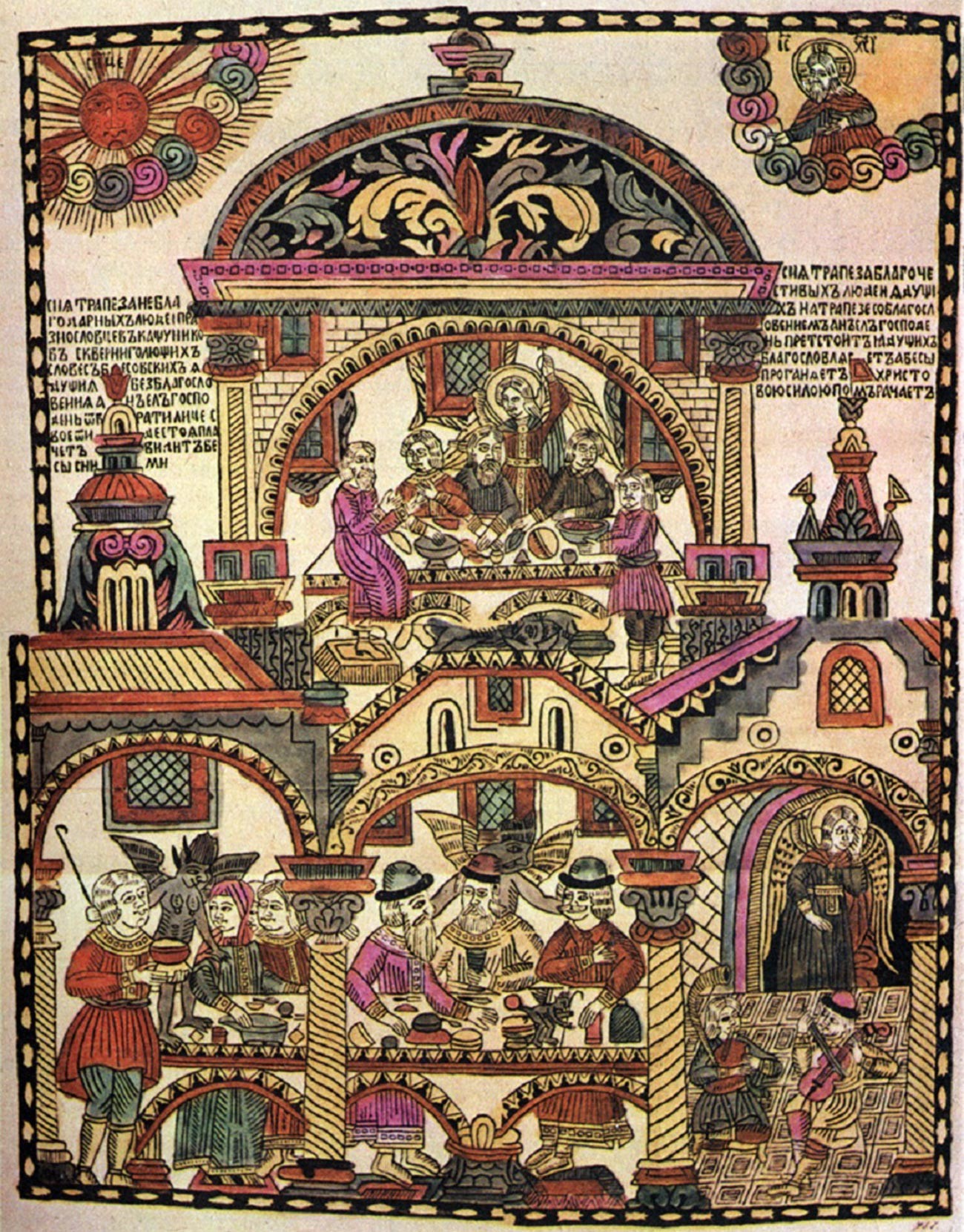

Lubok ‘Feast of the pious and impious’, 18th century.

Public domainDespite the state’s efforts to control the production of luboks, woodcuts continued to be sold aton market stalls. In addition, the country was inundated with lubok prints making fun of the emperor and his reforms.

Lubok ‘How mice buried a cat’, 18th century. Peter the Great was often depicted as a ferocious cat. This engraving is a satire on the emperor’s funeral.

Public domainIn the 19th century, lubok prints showed their effectiveness as a form of mass media. During the Patriotic War of 1812, war luboks were in demand. Exact dates, real names and details turned lubok prints into a key source of information. Some of the events were depicted in the pictures, while others were described in the captions. In addition to covering the facts, an artistic depiction of a certain historical episode added an emotional coloring to the verbal section of the lubok, stirring the reader’s imagination.

Lubok ‘The Battle of Kulikovo’. I.G. Blinov, second half of the 19th century.

I.G.BlinovIn addition to tales of military glory, biblical stories and folklore, lubok prints depicted moments from peasants’ everyday life, for example, the process of weaving bast shoes.

Lubok ‘A man weaving bast shoes’, 18th century.

Public domainIn many respects, lubok prints served as works of fiction for peasants.

Lubok ‘The Little Humpbacked Horse’, 19th century.

Public domainIn addition, lubok prints depicted various “cock-and-bull stories”. In effect, they were the memes of pre-revolutionary Russia.

Lubok, 18th century. The caption reads: “A bear and a she-goat are idling away the time, having fun playing their music. The bear has put his hat on and is blowing his pipe, while the gray she-goat has put on a blue sarafan and with its trumpets and bells and spoons is jumping and squat dancing.”

Public domainLuboks were also used to ridicule the vanity and greed of the upper classes.

Lubok ‘A dandy and a venal woman’, 18th century. Caption: “I have had this habit since a young age: without money, I do not make love to any man, however handsome. I am not at all averse to making a profit and would be ready to make love to a bull for money.”

Public domainThe introduction of lithography in the 19th century made the production of lubok prints cheap and fastquick. However, this had a negative effect on quality and most of luboks and fairy tales had to be reprinted.

Lubok ‘The Tale of the Fisherman and the Fish’ based on A.S. Pushkin’s fairy tale, 1878.

Public domainThe year 1918 became a turning point in the history of the lubok. Printing came under state control and was subjected to ideological censorship. Nevertheless, the lubok tradition could still be traced in the works of 20th century artists, for example, Wassily Kandinsky.

Fresco ‘An Amazon in the mountains’, W. Kandinsky, 1918.

W.KandinskyOver time, the lubok ceased to be a mass art and these days it can be found only in museums.

That said, Russian artists are trying to revive the lubok tradition. One famous author of 21st century lubok prints is Viktor Penzin. He creates modern lubok prints using traditional methods - engraving and then painting in watercolors. His works can be found in the State Tretyakov Gallery and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

Lubok ‘St. George the Victorious’, 1967-1980.

Viktor PenzinAnother contemporary artist Andrei Kuznetsov creates online lubok prints on topical issues of the day, full of grotesqueness and allegories. His works often feature characters from foreign moviesfilms and Soviet animated cartoons.

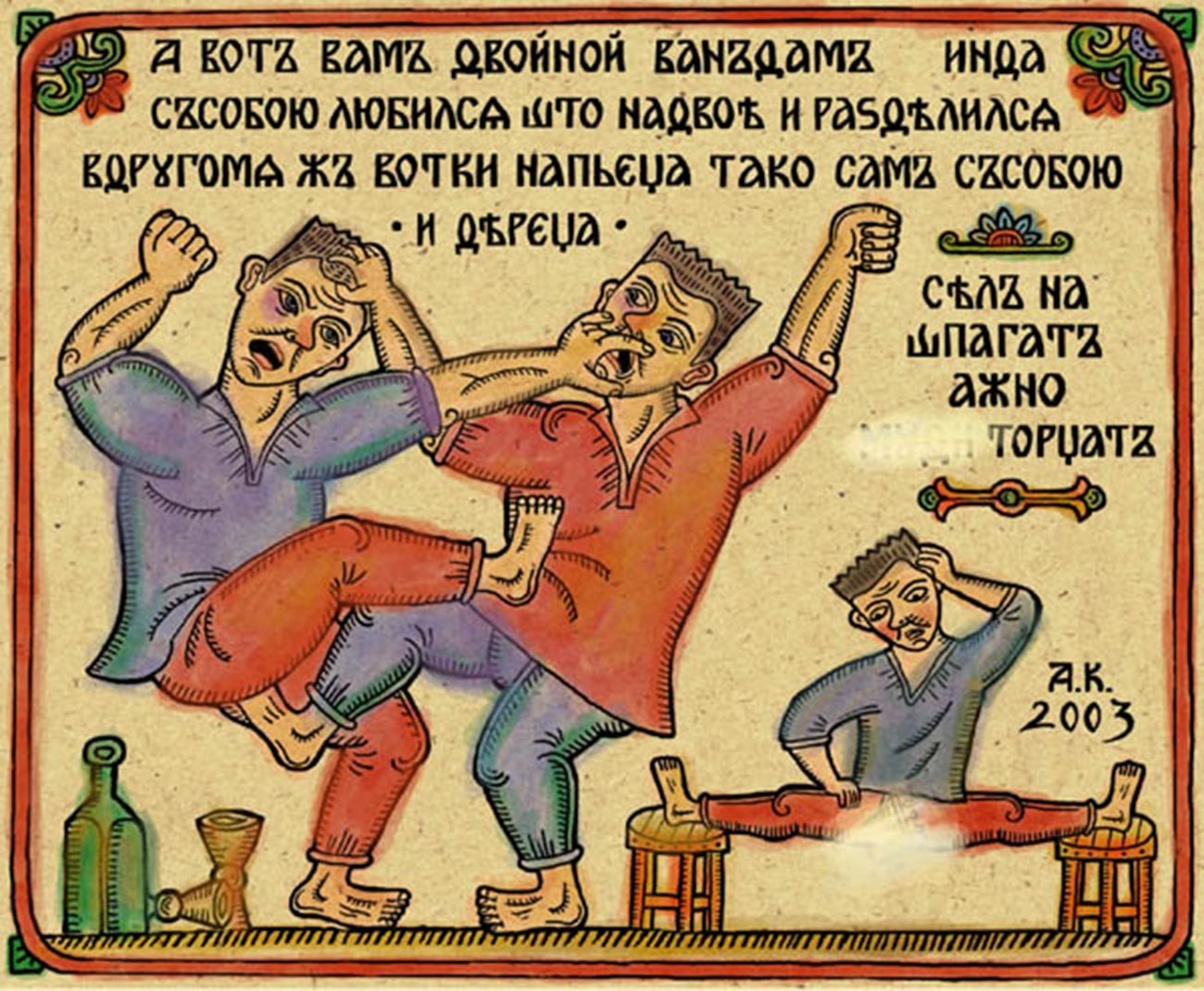

Lubok ‘Beating is a sign of love’, 2003. Caption: “Here is a double Van Damme: he loved himself so much that he split into two. Whenever he has vodka, he starts fighting with himself.”

Andrei Kuznetsov

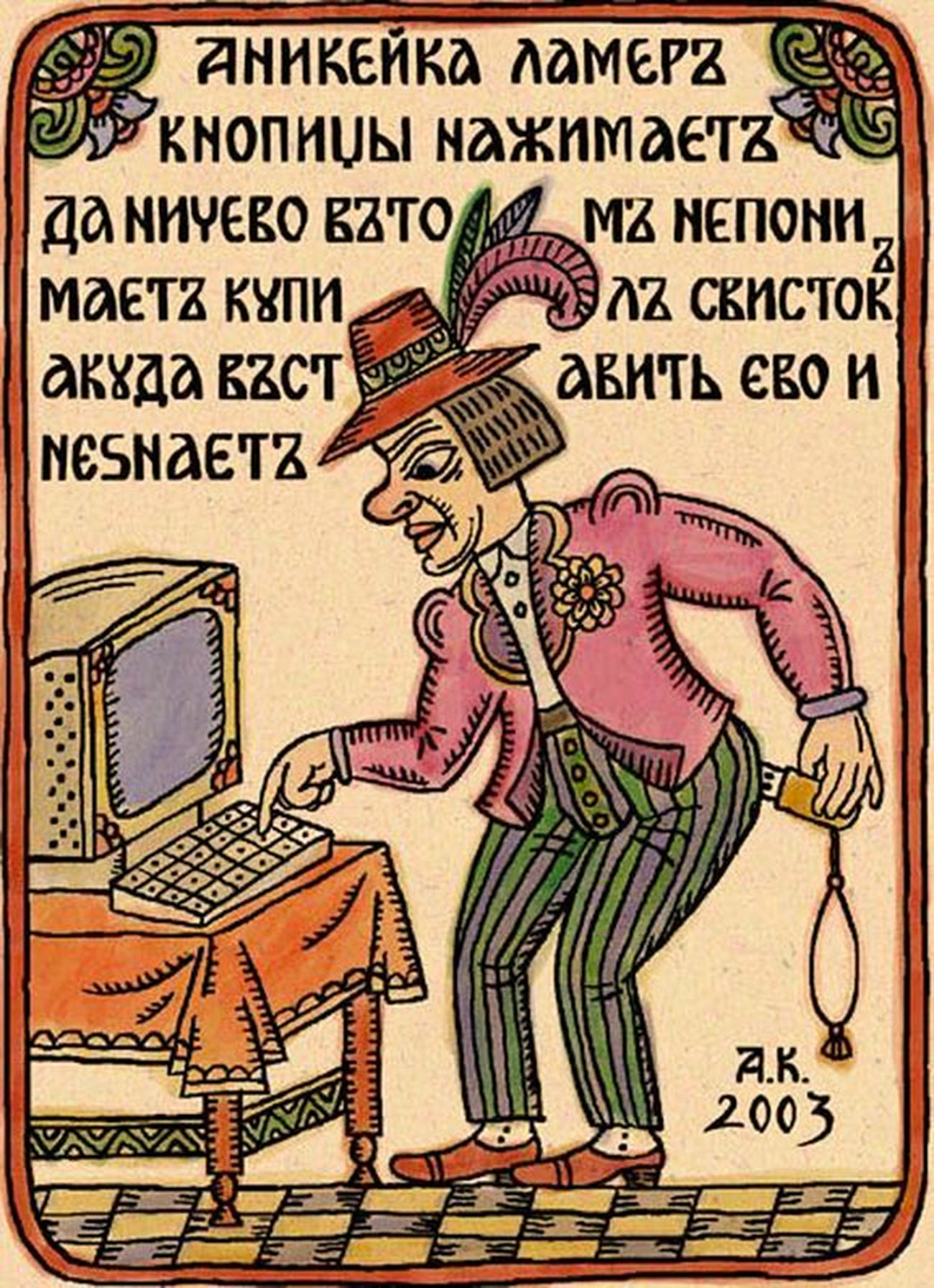

Lubok ‘Anikeyka’, 2003. Caption: “Lamer Anikeyka is pressing the keys, but he does not have a clue; hbe has bought a USB device but has no idea where to insert it.”

Andrei KuznetsovIf using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox