Why do Russian churches have onion-shaped domes?

Early Christian basilicas and ancient Roman temples often had one huge dome in the shape of a hemisphere. Russian churches, however, could be crowned with a various number of domes that came in different shapes.

If a church has three domes, they symbolize the Holy Trinity; five domes symbolize Christ and the Four Evangelists; while 13 domes are usually dedicated to Christ and the Apostles. There could even be 25 domes, as, for example, in the first stone Orthodox church built in Kievan Rus in the late 10th century. In addition to Christ and the Apostles, the other domes symbolized the Twelve Prophets. That church has not survived.

A reconstruction of what the Church of the Tithes in Kiev may have looked like

Voevoda (CC BY-SA 4.0)But the domes of that church did not at all look like onions. For a long time, Russian church architecture made widespread use of so-called helmet domes, whose shape resembled the helmets of Russian bogatyrs. Domes like that can be found on the oldest surviving churches.

Cathedral of St. Sophia in Veliky Novgorod, 11th century, one of the oldest surviving churches in Russia

User№101 (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Assumption Cathedral in Vladimir, 12th century

Ghirlandajo (CC BY-SA 4.0)

John the Baptist Cathedral in Pskov, 13th century

A.SavinHowever, onion domes became one of the symbols of Russia and the main distinguishing feature of Orthodox church architecture. The shape symbolizes the flame of a candle. "It is the crown of a church, like a fiery tongue crowned with a cross and tapering towards the cross...," wrote religious philosopher Yevgeny Trubetskoy in his treatise, Three Essays on the Russian Icon.

Church of the Transfiguration on the island of Kizhi in the Republic of Karelia, 17th century

Getty ImagesThe 'onion' is the final part of the dome, sitting on a cylindrical base (called tholobate, or the drum), and the diameter of the onion dome is wider than the drum.

Domes of the Verkhospasskiy Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin

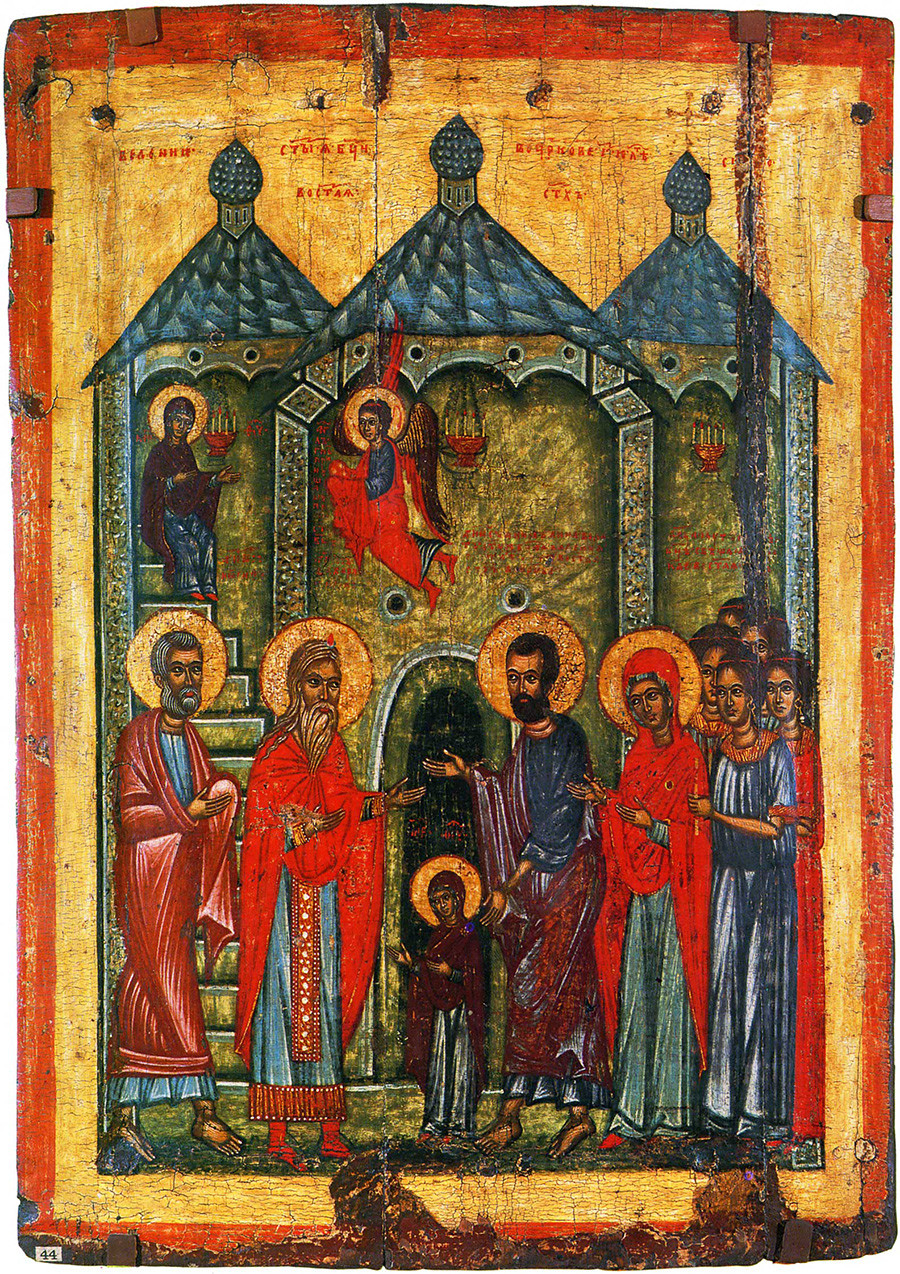

Legion MediaHistorians have different theories as to when onion domes first appeared and, most importantly, what served as an inspiration for them. These domes can be found on numerous miniatures and icons starting from the late 13th century. Although the churches depicted on those miniatures have not survived.

The Presentation at the Temple. An icon from the village of Krivoye, Novgorod school, first half of the 14th century

State Russian MuseumSo where did this shape come from? Some scholars believe that it was inspired by images of the Edicule (the chapel above the Holy Sepulcher), which is believed to have had its onion dome already in the 11th century.

Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem

Hartmut Pöstges/Global Look PressOther historians believe that onion domes may have been borrowed from the Islamic architecture of mosques, which in the 15th century often had elongated domes.

The Gur-e Amir mausoleum in Samarkand, early 15th century

Egmont Strigl/Global Look PressSo why did this shape become so widely used? There are different theories trying to explain it. According to one, the bulbous form is more practical, as it prevents snow and water from accumulating on the roof. According to another theory, the onion shape was easier to execute in wood than the helmet one, and when church construction shifted from wood to stone architecture, that form of the dome was also adopted for stone churches. Yet another theory suggests that medieval architects sought to achieve elongated, taller forms in church architecture, which was in line with the Gothic style prevalent in Europe at the time.

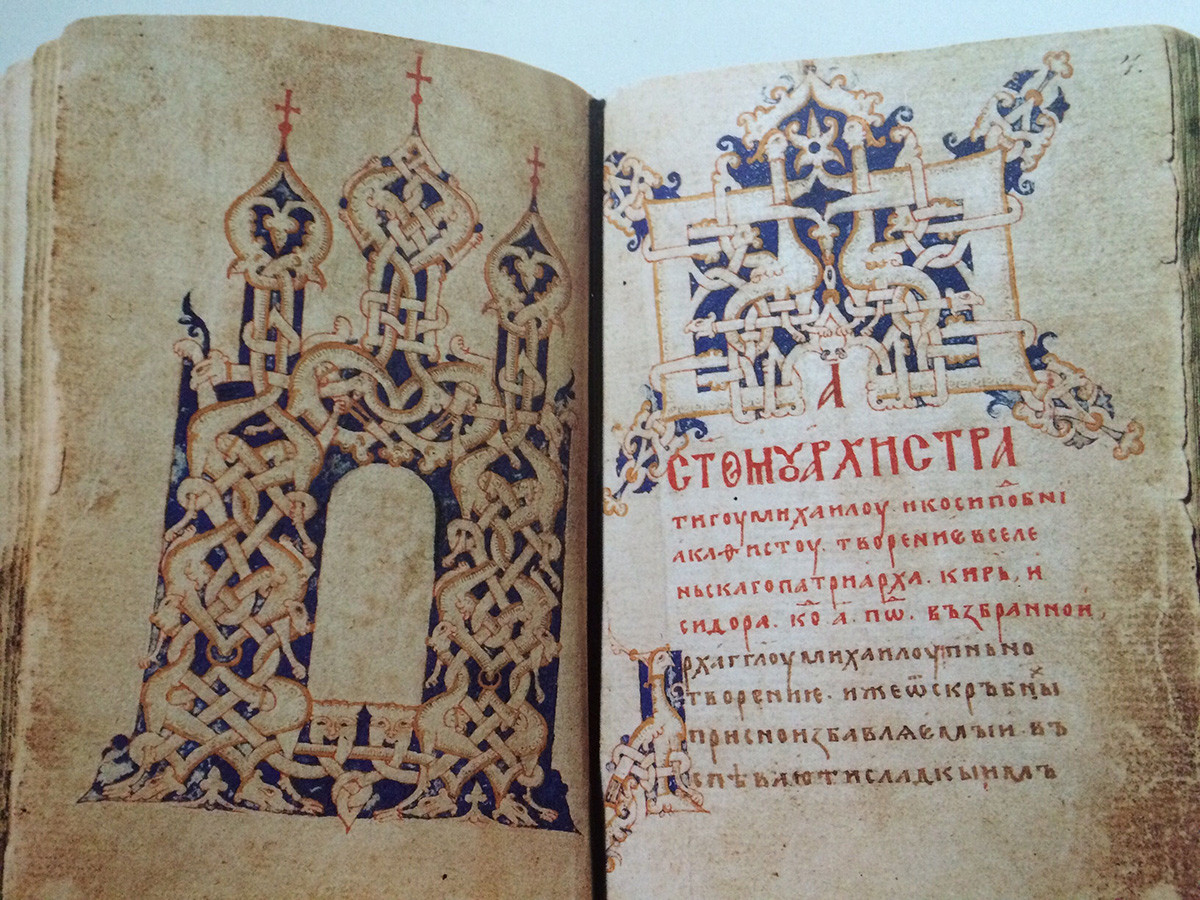

Prayer book from the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery, 1407

Public domainMost of the onion-domed churches that have survived to this day were built in the 16th century and later. One of the most famous of them is St. Basil's Cathedral on Red Square, built during Ivan the Terrible's reign.

St. Basil's Cathedral, mid-16th century

Igor Sinitsyn/Global Look PressA factor that may have contributed to the widespread use of onion domes was the appearance in the 16th-17th centuries of tent-like churches. The tented roof - a tall, multifaceted pyramid - was an alternative to the drum dome. Scientists have concluded that medieval architects must have thought it not enough to simply crown the hipped-roof structure with a cross, and started adding onion domes to it. That design became widespread both in wooden and stone churches and can still be seen in the Russian North, as well as in Moscow, Vladimir and Suzdal. In addition, in many churches with more familiar architecture, bell towers are crowned with tented roofs.

John Chrysostom Church, Arkhangelsk Region, 17th century

Konstantin Goncharov

Church of the Feast of the Transfiguration in the village of Ostrov, Moscow Region, 16th century

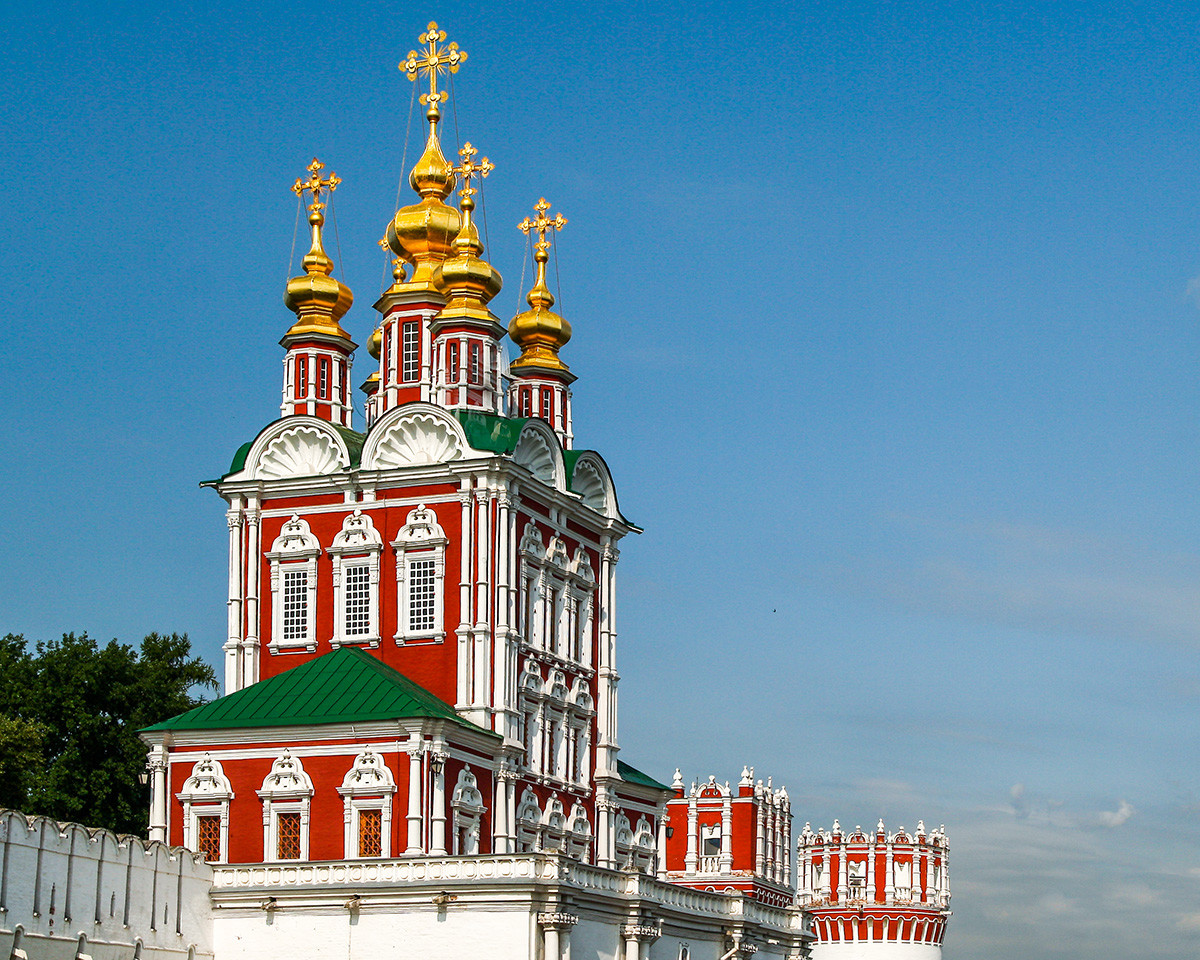

Ludvig14 (CC BY-SA 4.0)Like the number of domes, their color also has a symbolic meaning. So, familiar-looking golden domes symbolize heavenly glory and are used to crown cathedrals or the main churches at monasteries and convents. These cathedrals are often dedicated to Christ or the Twelve Great Feasts (the main 12 holidays celebrated by the Russian Orthodox Church).

Gate-Church of the Transfiguration at the Novodevichy Convent in Moscow, 17th century

Getty ImagesBlue domes with stars are used on churches dedicated to the Mother of God or the Birth of Christ.

Cathedral of the Nativity in Suzdal, 18th century

Legion MediaGreen domes are typical of churches dedicated to the Holy Trinity or to individual saints – churches dedicated to the latter sometimes also have silver domes.

Church of the Birth of John the Baptist in Uglich, 17th century

Roman Denisov/Global Look PressBlack domes are mostly used on monastery churches.

Assumption Cathedral of the Solovki Monastery, 16th century

Legion MediaIt is believed that the multi-colored domes of the Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed in Red Square symbolize the beauty of Heavenly Jerusalem, which, according to legend, the holy fool saw in a dream.

Who were 'holy fools'? Click here to find out more.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox