7 architects behind the Soviet Union’s most iconic buildings

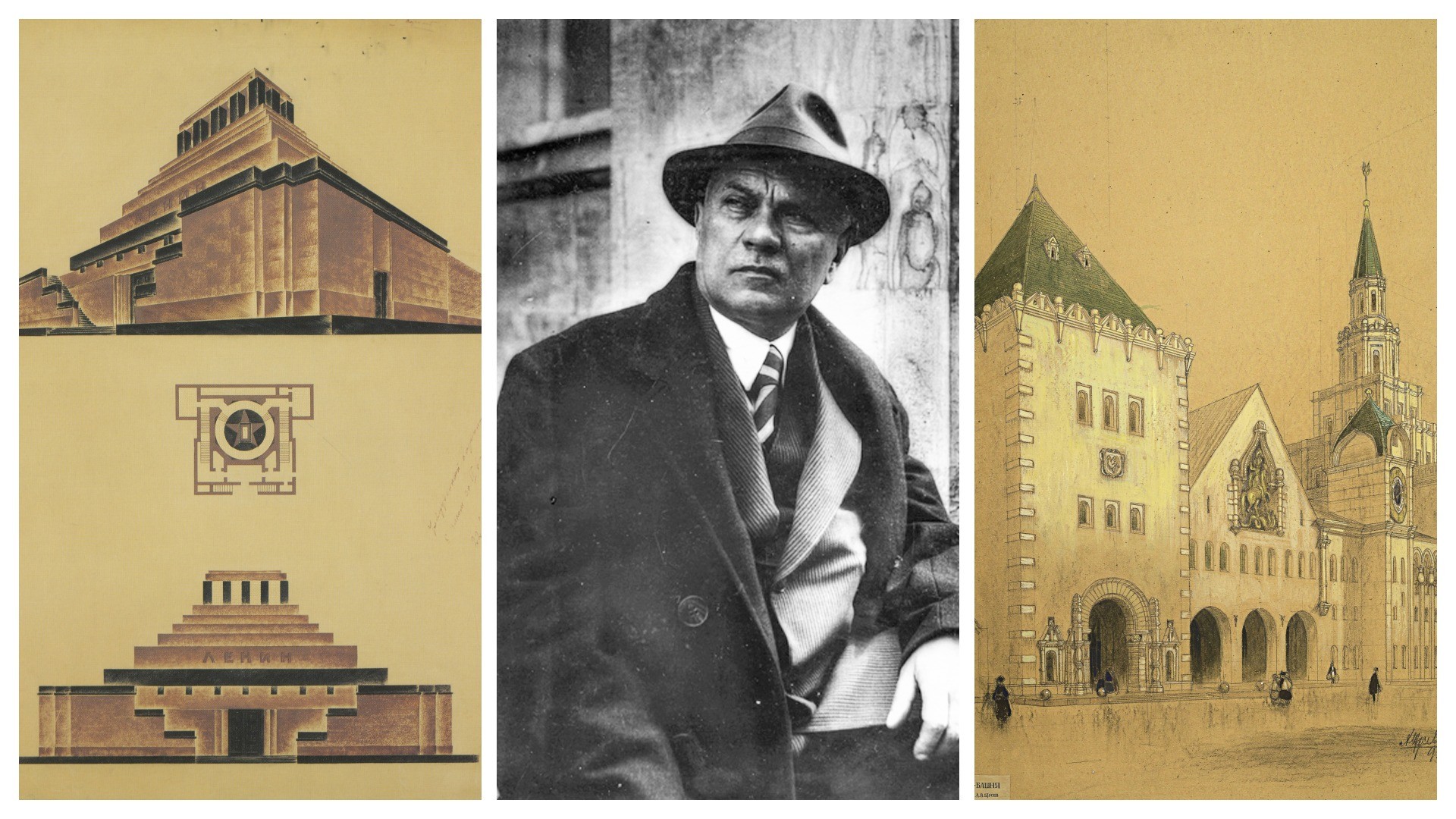

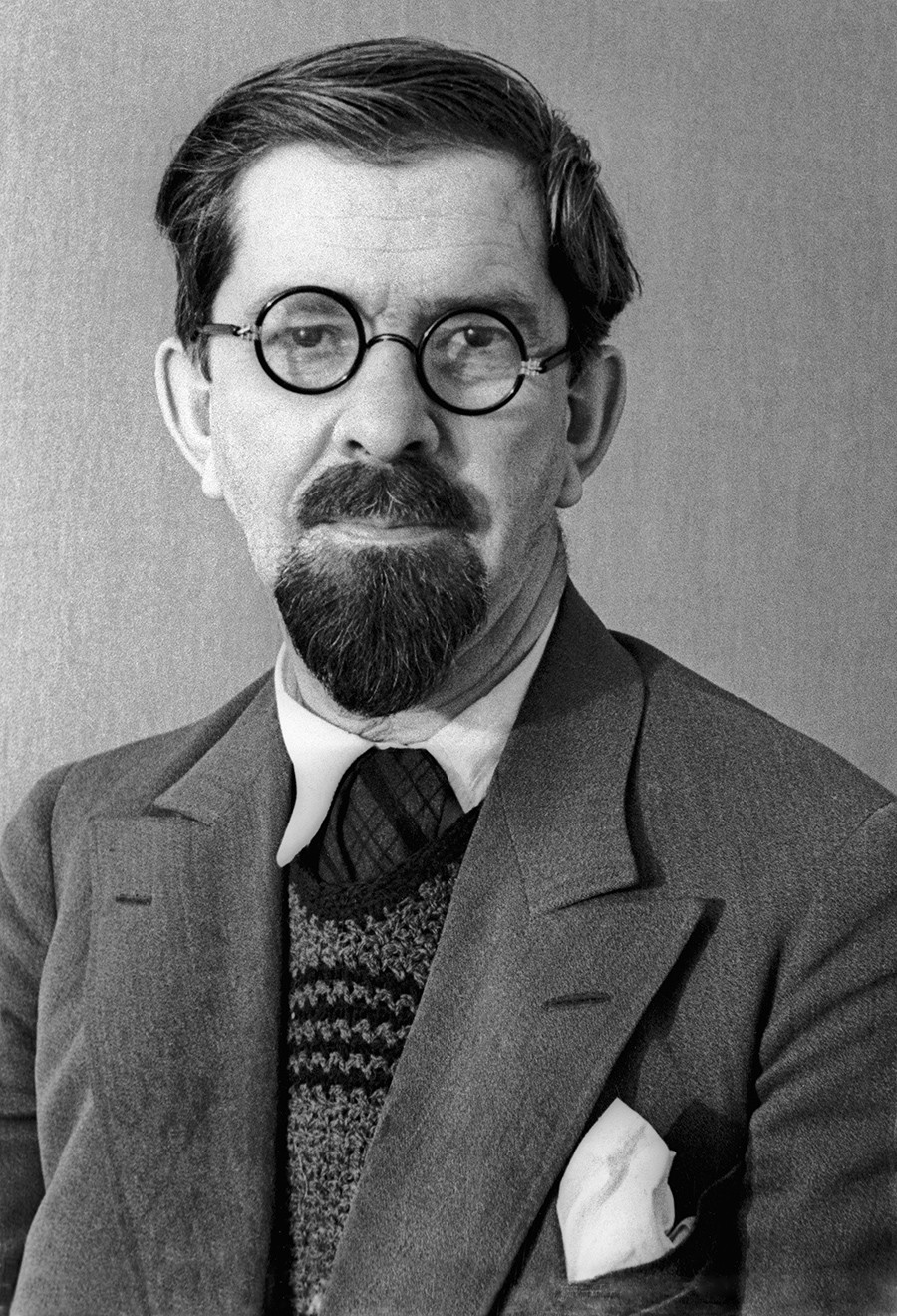

Alexey Shchusev and his famous creations: Lenin's Mausoleum and Kazansky Railway Station in Moscow.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images1. Alexey Shchusev: From Lenin’s Mausoleum to Moscow’s most stunning metro station

With its marble columns, crystal chandeliers, and elaborate mosaic panels, the Komsomolskaya metro station in Moscow is a veritable palace and rightfully considered the grandest station in the city. It was the last project of Alexey Shchusev (1873-1949), a renowned architect who held numerous titles and helped redefine Moscow’s appearance. He worked in a variety of styles, including Art Nouveau, Art Deco and Constructivism. Before the Bolshevik Revolution, Shchusev mainly designed churches and country estates (including the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent).

Mausoleum on Red Square.

Legion MediaIn the Soviet period, he became famous after the construction of the Vladimir Lenin Mausoleum on Red Square (1926-1930). He was also the architect behind Kazansky railway station in Moscow (constructed between 1912 and 1940), the Moskvoretsky bridge (1938), the Moskva Hotel on Okhotny Ryad street (originally built in the 1930s, the building standing in its place now is a replica from 2013) and a number of residential buildings.

Komsomolskaya metro station,

Legion MediaBut Shchusev did not limit himself to designing individual buildings. He led a team of architects who developed a plan for the general reconstruction of Moscow. They wanted to turn the Soviet capital into a garden city. They advocated for moving administrative buildings to Khodynka Field in order to preserve old buildings in the city center, creating a complex of central railway stations, connecting different railway lines and alternating residential areas with parks. While Shchusev's plan was not ultimately adopted, some of its elements—such as the radial-ring layout of the city—were included in the 1935 plan. In the end, Moscow unfortunately lost many architectural masterpieces that were demolished in order to clear space for new buildings. These included the Kitay-gorod wall, the Sukharev Tower and the Strastnoy Monastery.

2. Ivan Fomin: The creator of "proletarian classicism"

What would happen if you combined strict constructivist forms with antique columns? This is how Ivan Fomin (1872-1936) envisioned the ideal buildings for the Soviet people. He called his style “Proletarian classicism” or “Red Doric style.”

The ‘Dynamo Society’ building.

Ludvig14 (CC BY-SA 4.0)In the first years after the revolution, Fomin took part in the general reconstruction of St. Petersburg, and the Field of Mars as it looks now is his creation. But his ideas were expressed in a particularly interesting way in the city of Ivanovo, the textile capital of the USSR, where he built an entire university quarter, including lecture halls and a library.

Ivanovo Chemistry-Technology Institute.

Alexei Beloborodov (CC BY-SA 4.0)In Moscow, his most famous works are the residential building of the Dynamo society on Bolshaya Lubyanka street and the Russian Railways office in Krasnye Vorota square. Twin columns are an iconic feature that Fomin relished adding to his buildings.

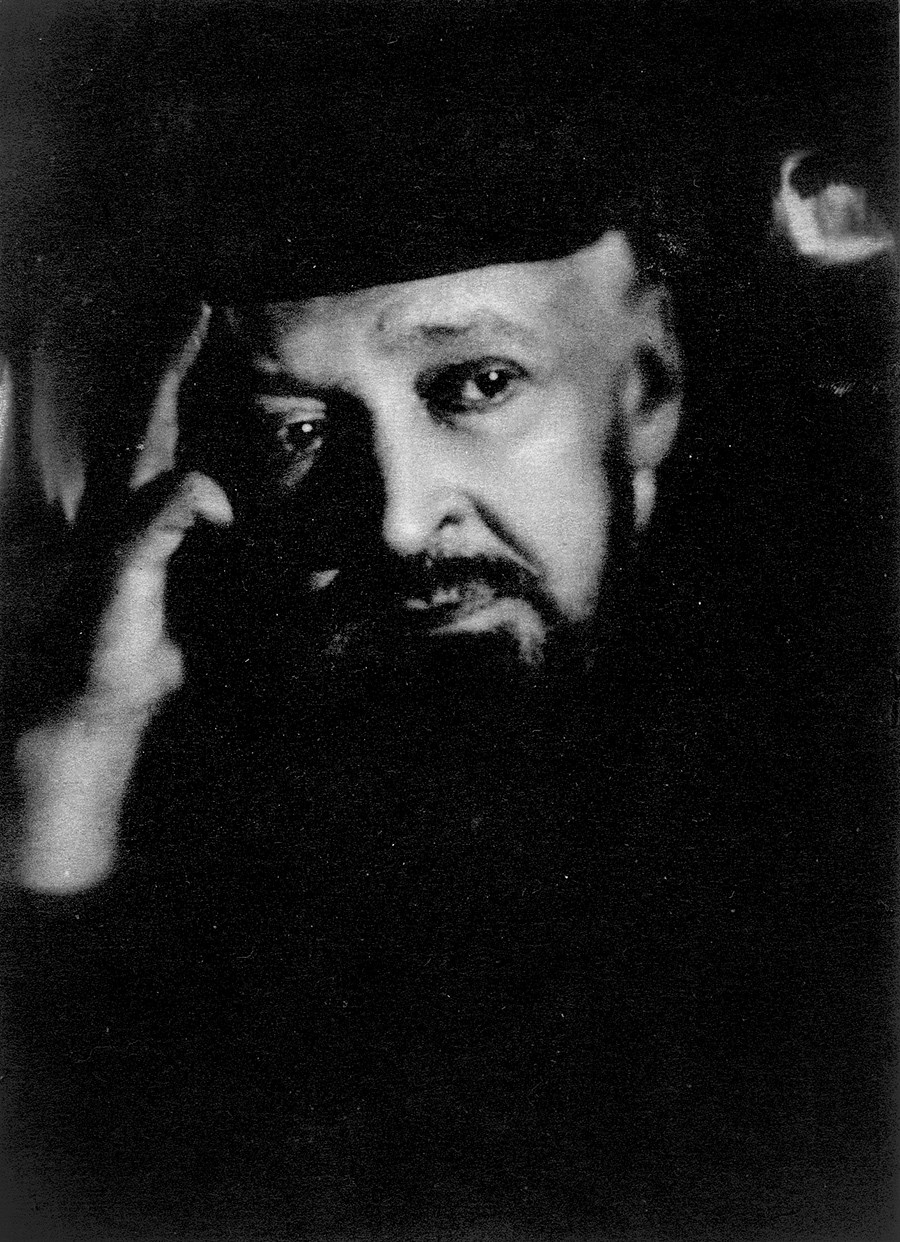

3. Konstantin Melnikov: The main avant-garde artist in architecture

Moscow in the 1920s threw itself into the avant-garde, and Konstantin Melnikov (1890-1974) was the movement’s undisputed leader. Collaborating with Alexey Shchusev and Ivan Zholtovsky, he set out to transform Moscow's architectural appearance.

Rusakov workers' club built In 1927-1928 In Moscow.

Legion MediaHis particular area of expertise was the design of community centers (for example, the Rusakov Workers' Club) and garages for Moscow transport (his trapezoidal Bakhmetyevsky garage and the Gosplan garage with its headlight-like round window are considered cultural monuments today). But perhaps the most unusual building that Melnikov built was his own house and workshop, which was constructed in the late 1920s and has a cylindrical form.

Melnikov house-museum.

Vladimir Astapkovich/SputnikMelnikov also designed the central part of Gorky Park, which still remains almost a hundred years later. In the last years of his life, he taught architecture.

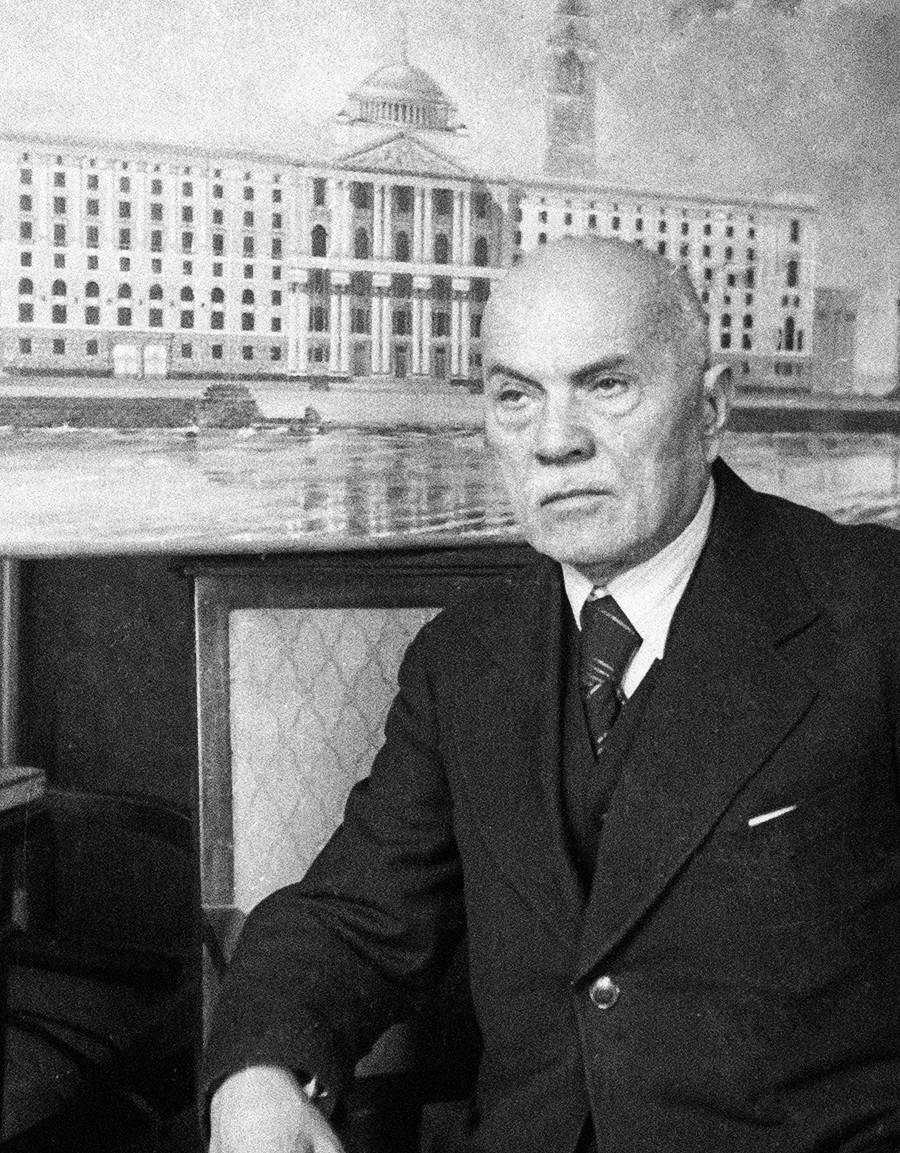

4. Lev Rudnev: Leading architect of the Stalinist Empire style

After the war, Joseph Stalin wanted eight high-rise buildings to be constructed in Moscow to mark the 800th anniversary of the city. In the end, only seven were built, and they became known as the Seven Sisters.

Moscow State University.

Legion MediaOne of the project’s main architects was Lev Rudnev (1885-1956), who had worked with Fomin on the layout of the Field of Mars. Rudnev designed the main building of Moscow State University on Vorobyovy Gory, the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw, the Military Academy and the building of the Ministry of Defense in Moscow, as well as the Chkalov Stairs in Nizhny Novgorod.

The building of the Ministry of Defense in Moscow.

Legion MediaThese projects epitomize the Stalinist Empire Style. Rudnev survived the siege of Leningrad and after the war actively took part in the restoration of Riga, Voronezh and Moscow.

5. Ivan Zholtovsky: From rich mansions to industrial sites

Before the revolution, Ivan Zholtovsky (1867-1959) mainly designed country villas and townhouses for the wealthy residents of Moscow. In the Soviet period, he worked together with Shchusev on large-scale neoclassical construction projects.

The power plant on the Raushskaya Embankment.

PAO Mosenergo (CC BY-SA 3.0)For example, he designed the building of the country's oldest thermal power plant on the Raushskaya Embankment (the plants still generates electricity for the Kremlin!), rebuilt the Moscow hippodrome, designed several sanatoriums in Crimea, the Riviera bridge in Sochi and a number of apartment blocks for party workers.

A house with a turret on Smolensky Boulevard.

A.SavinThe most impressive of Zholtovsky's residential buildings was the so-called "house with a turret” on Smolenskaya Square, which is one very few buildings with its own entrance to the metro. After the war, Zholtovsky's workshop took part in one of the first construction projects for panel buildings.

6. Vitaly Lagutenko: Author of the first Khrushchyovka apartment blocks

The architecture of post-war Soviet residential buildings is often dismissed as dull and faceless, but panel houses made it possible to provide millions of Soviet people with housing within a short period of time. Many architects worked on creating a standard design for low-cost apartment blocks, but in the end the most successful project was by Vitaly Lagutenko (1904-1969).

One of the houses in Moscow build by Lagutenko's project.

Artem Svetlov (CC BY-SA 3.0)The first K-7 series residential buildings were put up in the 1960s in Moscow, Saratov, Leningrad, Murmansk and other cities. Other architects began to develop on Lagutenko's idea, and soon plants were set up in many large cities to produce the reinforced concrete panels used in housing construction.

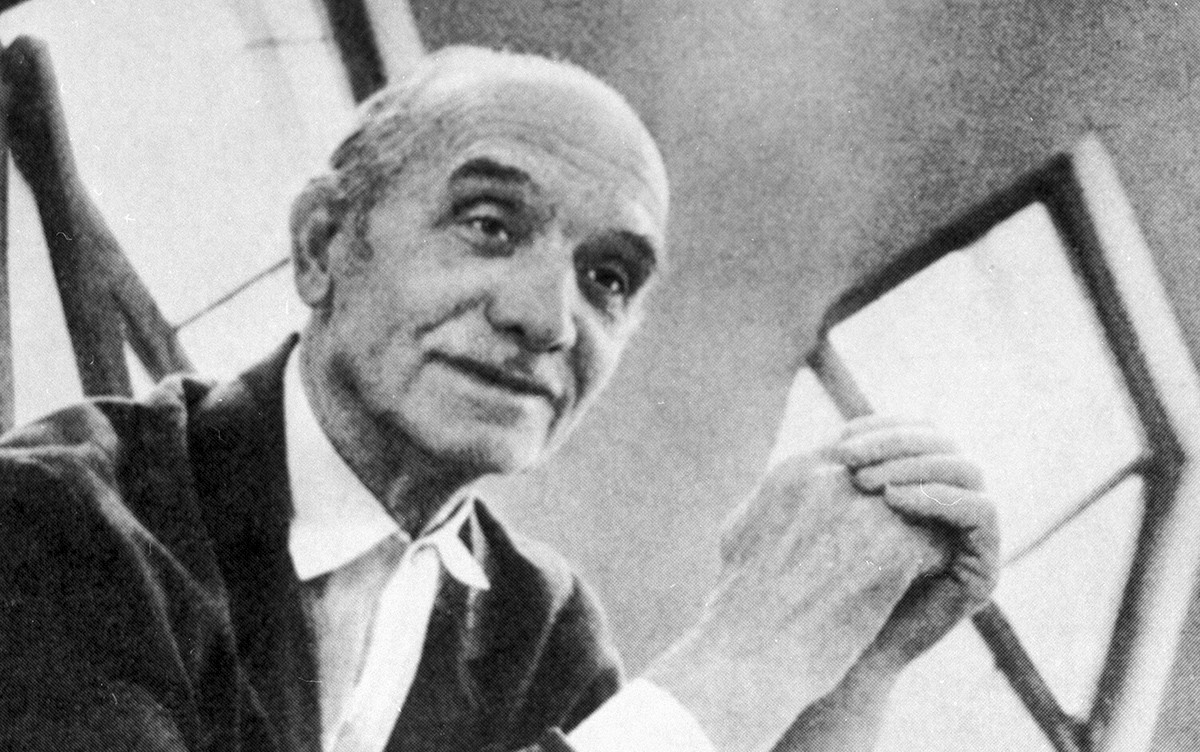

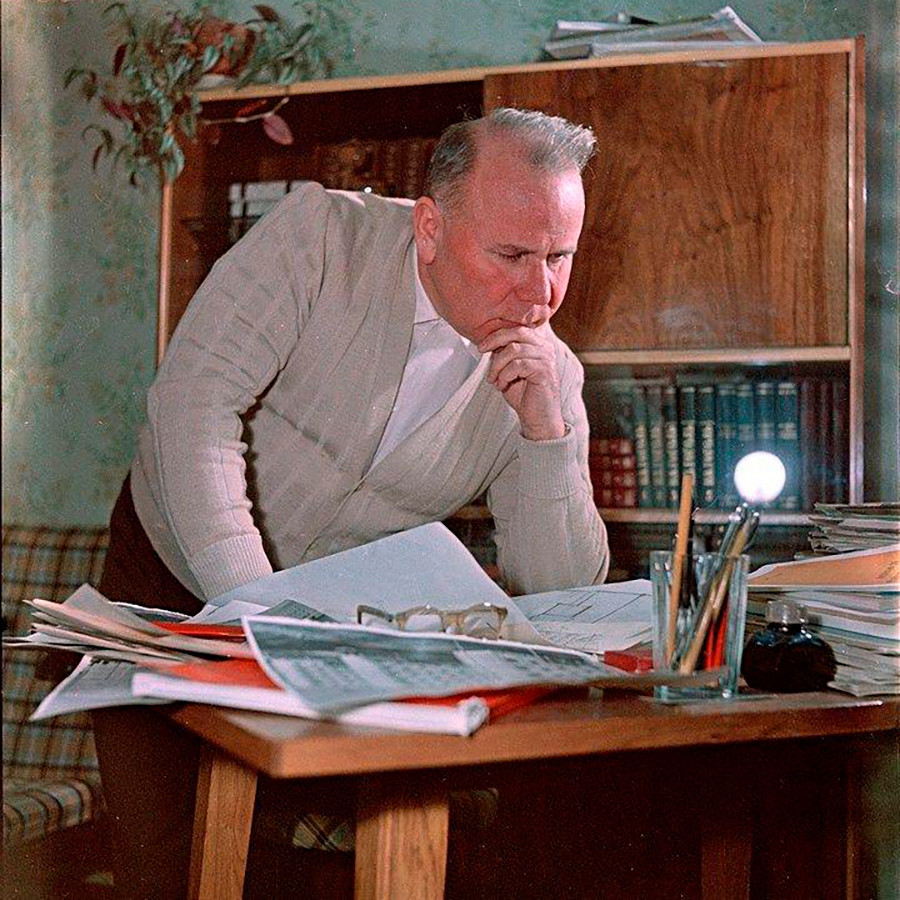

7. Mikhail Posokhin: Olympic Moscow

The Soviet capital underwent a major transformation before hosting the 1980 Summer Olympics. The idea was that foreign guests who visited the closed country ought to see it in all its splendor. Architect Mikhail Posokhin (1910-1989) was in charge of constructing the impressive Olympic stadium, which could accommodate 35,000 spectators and was the largest stadium in Europe at the time. Posokhin was also behind designing the book-like high-rise buildings on Novy Arbat street, along with the Expocentre and World Trade Center in Krasnaya Presnya.

Prospect Kalinina (Novy Arbat).

Boris Yelin/SputnikHe also worked on an experimental model neighborhood in the North Chertanovo district of the city, which consisted of high- and low-rise residential buildings that included everything—from swimming pools to libraries to restaurants—that residents would need in everyday life.

Russian Embassy in the U.S.

Aaron Siirila (CC BY-SA 2.5)Posokhin also designed buildings for state needs, including the Palace of Congresses in the Kremlin and the building of the Russian embassy in Washington.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox