Leo Tolstoy’s favorite Russian writers

Leo Tolstoy’s library contains an inconceivable number books on all kinds of topics and in many different languages: Tolstoy had an excellent reading knowledge of about 15. From ancient Eastern thinkers to the latest titles in Russian literature, he tried to be acquainted with everything. Tolstoy wrote reviews of many works, and described his impressions in letters to friends and publishers. In the 1890s, he even compiled a list of what he considered the most important books, sorted by the age at which they should be read.

He was known to be very fond of Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens, while his disdain for William Shakespeare, and even Alexander Pushkin, is legendary. He was dismissive of the plays of Anton Chekhov. And generally preferred prose to poetry.

What Russian writers did he value the most?

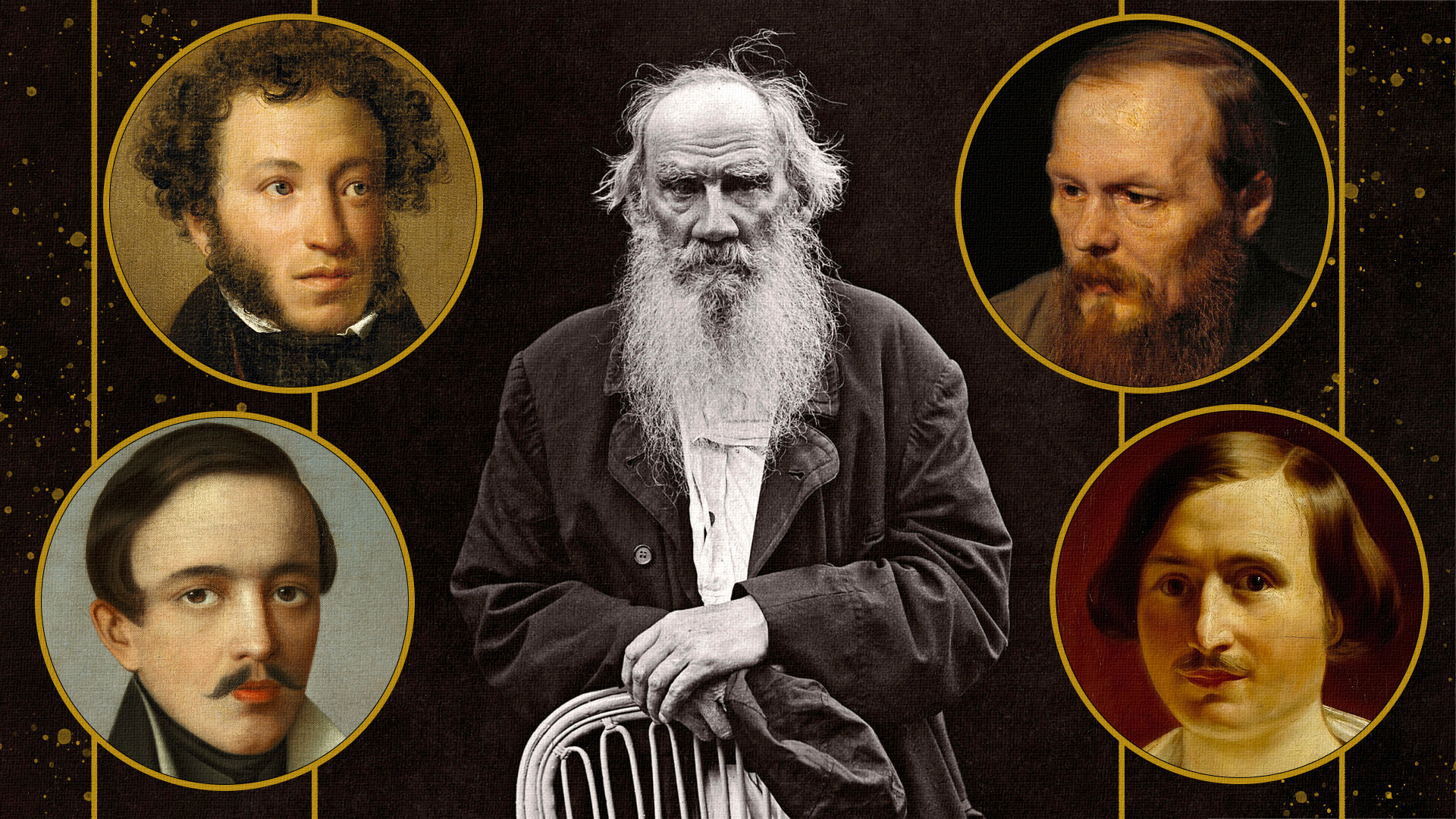

Alexander Pushkin

Portrait of Alexander Pushkin by Orest Kiprensky

Corbis/Getty ImagesNo, we’re not contradicting ourselves. Pushkin the poet (as well as Pushkin the playwright) Tolstoy really did not like, writing: “Pushkin’s Boris Godunov is a weak imitation of Shakespeare.” Tolstoy was unhappy, and perhaps envious, that Pushkin was so celebrated, that monuments had been put to him. After all, “his merit lies solely in the fact that he wrote poems about love, often very indecent ones.”

The high-minded Tolstoy felt disdain for this “man of lax morals” who had died in a duel, “that is, trying to murder a fellow human being!”

That said, Tolstoy thought highly of Pushkin’s prose and simply adored TheBelkin Tales collection: “Every writer should study them. I did it the other day and I cannot convey to you the beneficial effect this reading had on me.” Tolstoy also loved The Queen of Spades.

Researchers even consider the unfinished fragment “Guests gathered at the dacha” as the impetus behind Anna Karenina. Tolstoy admired its beginning, which plunges the reader into the epicenter of the plot with no superfluous prefaces or descriptions. He applied this technique in Anna Karenina, following the famous “happy families” aphorism with the phrase: “Everything was in confusion in the Oblonskys’ house.”

In his list of important books, Tolstoy also recommended Eugene Onegin, which, although written in verse, is a great novel.

Mikhail Lermontov

Portrait of Mikhail Lermontov by Gury Krylov

Heritage Images/Getty ImagesTolstoy likewise appreciated Russia’s second most important poet exclusively for his prose. He reread A Hero of Our Time on several occasions and included it in his list (especially the story “Taman”).

Admittedly, he respected Lermontov more as a soldier (Tolstoy himself served in the Caucasus) than as a writer. In Lermontov, he glimpsed “the very highest moral demands lying beneath the cloak of Byronism.” Questions of morality gnawed the soul of the later Tolstoy. Literary scholars also believe the two writers are united by a morbid dissatisfaction with themselves and a tendency to self-castigation.

Nikolai Gogol

Portrait of Nikolai Gogol by Fyodor Moller

Legion Media“Gogol has tremendous talent, a beautiful heart and a small, timid, tremulous mind,” Tolstoy wrote about the author of Dead Souls. In his characteristic manner, Tolstoy approached all Gogol’s works critically, and found much to his distaste.

For instance, despite his generally positive attitude to the play The Government Inspector, he described the silent, pathos-filled finale as “execrable nonsense.” He also disliked the unfinished second volume of Dead Souls, which, incidentally, Gogol himself burned, considering it a failure.

Tolstoy accused his literary forebear of replacing true faith with superstition and of “ascribing to art a high meaning not intrinsic to it.” In addition, Gogol’s main device was laughter, and Tolstoy was unhappy that Gogol poked fun not only at nobles and officials, but also at peasants, who, in his opinion, did not deserve it.

What Tolstoy did like about Gogol, however, was his “folk” talent; the collection of stories about village life Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka Tolstoy read aloud to peasant children at the school he set up for them on his Yasnaya Polyana estate.

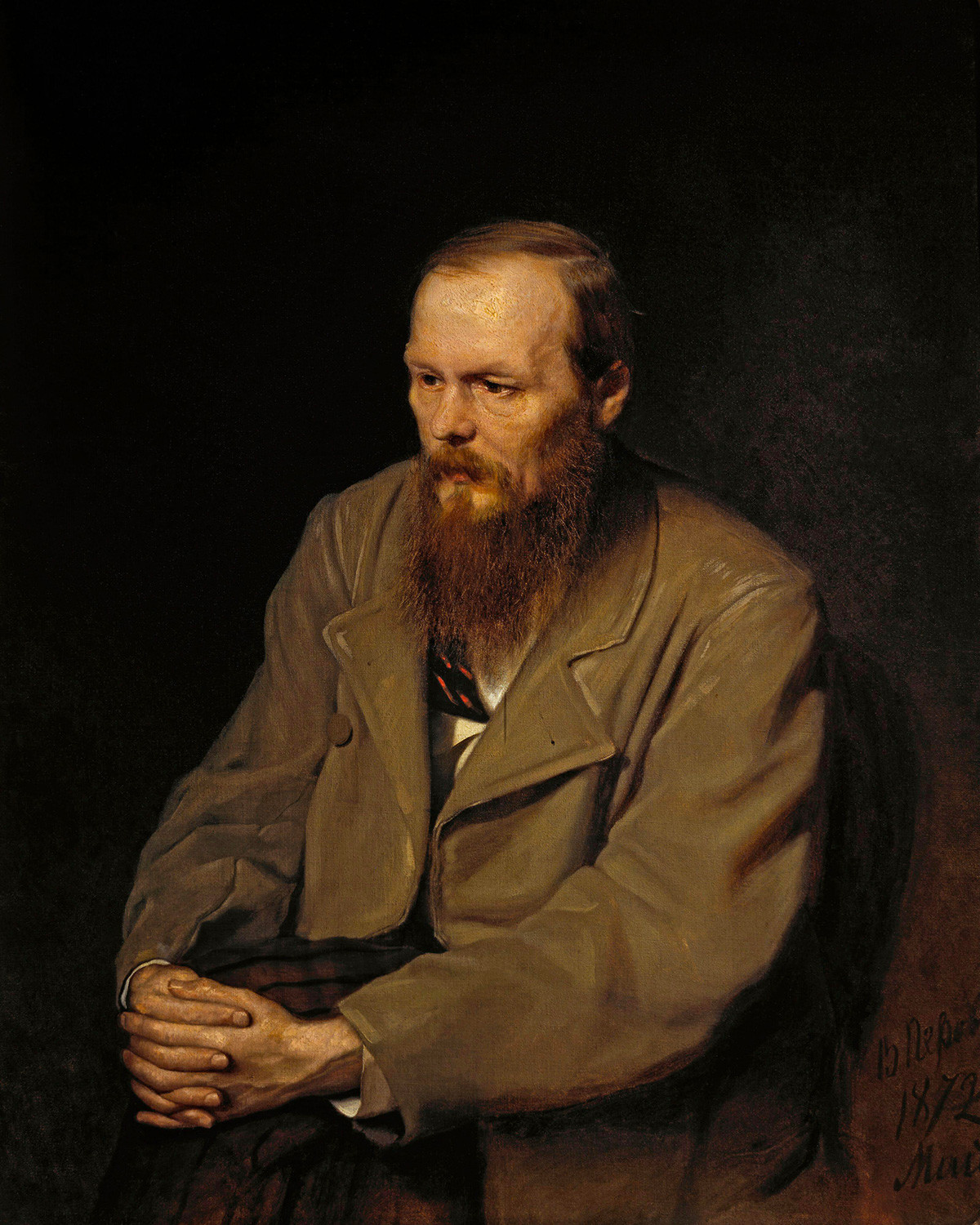

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Monographs and dissertations have been, and continue to be, written about the relationship between these two giants of Russian literature. They had different biographies, different artistic tools and different attitudes toward faith and humankind. But they were both great writers, which Tolstoy undoubtedly appreciated. When Dostoevsky died, Tolstoy suddenly announced that “he for me was the closest, dearest, most needed person,” and that he would have liked to ask him many things... Except that in life they never met.

“He is doubtless a real writer, on a truly religious quest, not like some Goncharov,” Tolstoy wrote about Dostoevsky. (Tolstoy thought little of both Goncharov and Turgenev, seeing in their novels only weak characters and “an abundance of commonplace love episodes.” Of Turgenev’s oeuvre, Tolstoy rated only Notes of a Hunter for its portrayal of ordinary folk, not pretentious nobles.)

In his treatise What is Art? Tolstoy cites Dostoevsky’s Notes from the House of the Dead as an example of “supreme religious art arising out of love for God and one’s neighbor.” Tolstoy also highly valued the novels The Humiliated and Insulted, Crime and Punishment and The Idiot.

The Brothers Karamazov, meanwhile, he initially gave up on, since it seemed to him that the characters all spoke the same language – that of the author, even a 15-year-old girl. This remark is justified, given the range that Tolstoy achieved in his own War and Peace, in which everyone – from naive wenches to grumpy old men, and even animals – all have their own unique voice.

Naturally, Tolstoy had other complaints about Dostoevsky. In his view, everything was mixed up: politics, religion, mysticism, which resulted in unstructured thinking and “technically weak” novels. It was obvious to Tolstoy that, unlike himself, Dostoevsky wrote in haste because he was forever in need of money.

“On the one hand, the best works of art of our time convey feelings of unity and fraternity (such are the works of Dickens, Hugo, Dostoevsky) <...>; on the other, they strive to impart feelings inherent not only to the upper classes, but able to unite all people without exception. Such works are still few, but the need for them has been recognized,” surmises Tolstoy in What is Art?

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox