Why Gogol burned the 2nd volume of his ‘Dead Souls’ novel

Russian literature’s most famous satirist planned his most famous work to consist of three parts, in the format of Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’ - with its own inferno, purgatory and paradise. It is the first volume, which was printed in 1842, that we know today as ‘Dead Souls’. That was the inferno part and it turned out really good: Gogol depicts a rich palette of bad characters and a wide range of various vices. Commenting on the first chapters written by Gogol (which were not included in the final version of the first volume), the great poet Alexander Pushkin said: “God, how sad our Russia is!”

Here is the plot synopsis: A member of minor nobility named Pavel Chichikov arrives in a small town and, in order to gain influence in society, pretends to be a landowner. However, the problem is that he does not have a single “soul”, that is, he has no serfs. So, he decides to resort to a trick facilitated by Russian bureaucracy. Each landowner in Russia had a list of serfs that was updated only once every few years. So, even if any of the peasants died, the landowner still paid taxes on them and they were listed as living until the next revision. Chichikov visits local landlords and asks them to sell him these dead souls... Each reacts to this unconventional proposal differently.

The Kukryniksy (Mikhail Kupriyanov, Porfiri Krylov, Nikolai Sokolov). Illustration for ‘Dead Souls’. Nozdrev and Chichikov

David Sholomovich/SputnikGogol himself called ‘Dead Souls’ a poem, although it was written in prose, but the form of the novel is reminiscent of an ancient poem in which the protagonist, Chichikov, travels through several repeating “circles of hell”, like Odysseus wandering from chimera to chimera. In addition, the “poem” contains lengthy lyrical digressions about Russia and Russians. The novel is considered the pinnacle of Gogol’s work - and one of the main keys to understanding the Russian soul. Its main character is not so much Chichikov as Russia itself.

What was the second volume supposed to be about?

In Gogol’s original plan, the second part was to be akin to Dante’s Purgatorio and the third, respectively, to Paradiso. “Its continuation is crystalizing in my head clearer and more majestic,” Gogol wrote to his friend, writer Sergei Aksakov.

The characters in the second part were not to be quite as bad as in the first volume. “Why, then, portray poverty, yes poverty and the imperfection of our life, digging people out of the wilderness, from the remote nooks and crannies of the state?” was how Gogol begins the second volume.

Take, for example, the character named Tentetnikov, whom we meet at the very beginning of the second volume: he leads an idle, bored life, but the author notes that he was once full of dreams and plans, but they all collapsed, due to the pettiness and futility of his service.

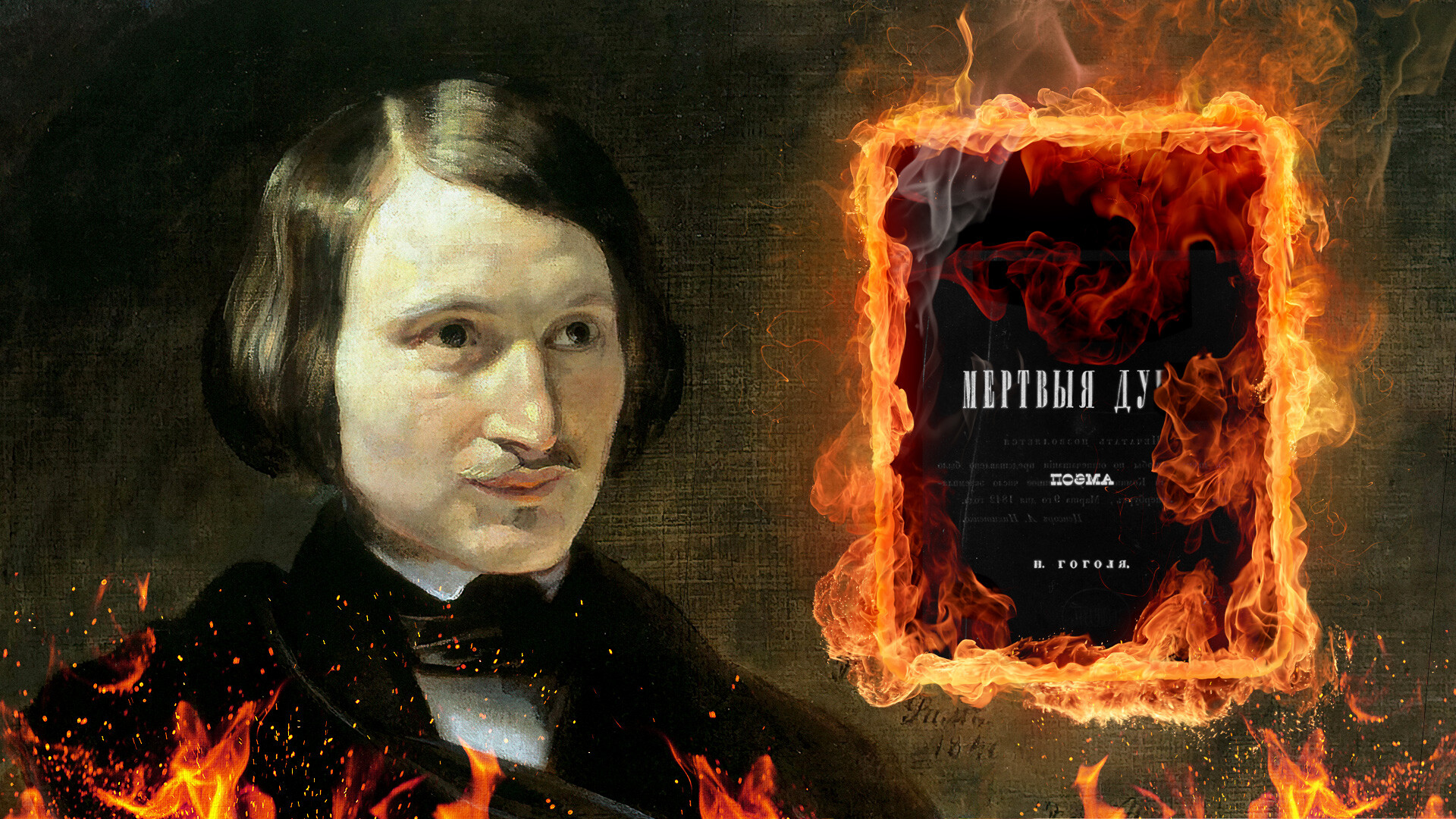

Fyodor Moller. Portrait of Nilokai Gogol, 1840

Tretyakov GalleryIn addition, Gogol wanted to find and show ways towards improvement. In particular, in the voice of his characters, he discusses how to get rid of corruption: in order to work well and not to steal, any civil servant needs the encouragement of his superiors.

If the first volume is full of Gogol’s depictions of mud and bad roads, in the second, he practically voices admiration for Russia’s vastness and landscapes.

Chichikov continues to visit local landowners and buy their dead souls, but, at some point, the box with all his papers is stolen. In addition, it becomes clear that someone is informing on Chichikov and his machinations. Chichikov, who, in the first volume, did not express any strong feelings, here becomes desperate, almost tearing his hair out. However, here the manuscript ends and we shall never find out what happened to him.

Why did Gogol think the second volume was no good?

The second volume of ‘Dead Souls’ was actually the last work that Gogol was writing before his death. Several years had passed since the publication of the first one and the author had changed: he was going through a spiritual upheaval and a painful craving for religion, accompanied by nervous breakdowns and anxiety.

“You are asking if ‘Dead Souls’ is getting written. Well, yes and no. It is getting written, but too slowly and not at all as I would like,” Gogol wrote to his poet friend Nikolai Yazykov. Gogol’s mental struggles made his work much harder. He could no longer write “as in my youth, that is, at random, wherever my quill leads me”, he admitted. Each line was a challenge.

The only person who read the second part of ‘Dead Souls’ was Archpriest Matfey, with whom the writer corresponded and had extensive and rather heated disputes on a variety of issues. Matfey criticized the second part of the novel, calling it harmful, and even asked Gogol to destroy it.

Mikhail Clodt. End of ‘Dead Souls’ (Gogol burning his manuscript). 1887

Abramtsevo museum-estateGogol himself felt that the second volume did not work out. He thought he was better at depicting bad characters and utter hopelessness. “The publication of the second volume the way it is would do more harm than good,” the author wrote in ‘Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends’. “Creating a few beautiful characters who reveal the generosity of spirit of our breed will lead nowhere. It will only arouse hollow pride and boasting…”

On February 24, 1852, Gogol burned the fruit of his labors, the almost finished second volume of ‘Dead Souls’. According to different theories, he burned the manuscript either in a fit of anger, or... by accident. Allegedly, he wanted to destroy only the drafts, but, by mistake, threw the clean copy into the fireplace, too. Be that as it may, Gogol was badly affected by what happened and died nine days later.

The chapters of the second volume that have survived to this day are a reconstruction of the surviving five notebooks. These individual chapters were most likely from the different versions that Gogol wrote. There are large gaps in them. In addition, they differ both in content and in tone, even the ink and paper are different. These surviving pages do not create a complete picture and the author’s intention remains unknown to us.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox