A renown surgeon professor named Philip Preobrazhensky lives in Moscow in a huge apartment. And, in it, he has a cabinet where he does experimental surgeries. He is already quite successful in rejuvenation procedures, but he wants to go further.

One day, he decides to transplant a human pituitary gland and testicles to a stray dog as an experiment. The surgery is more than successful, as the dog starts looking like a human being...

It's the mid-1920s, the Bolsheviks have recently seized the power and Soviet order is being implemented here and there. The professor is harassed for living in an apartment that’s too big for him, so the authorities make him share part of his apartment with several proletarians. The professor objects and can't accept the new rules. He can't imagine performing surgeries, eating dinner and sleeping in the same room.

Meanwhile, rumors about the successful surgery spread and people start to visit Preobrazhensky's house to take a look at the dog turning into a human.

Ironically, while the creator is against the Soviet new world order, his dog falls under their influence. The dog previously nicknamed Sharik files for documents and becomes Poligraph Sharikov.

Despite looking like a human, his behavior is far from human. More like a beast or, rather, a bastard. Sharikov harasses the professor's maids, steals his money and, finally, writes a denunciation against the professor. And all this while shouting political slogans.

Preobrazhensky can't take it anymore and performs a reverse surgery, removing the human organs from Sharikov. Slowly, he turns back into a dog.

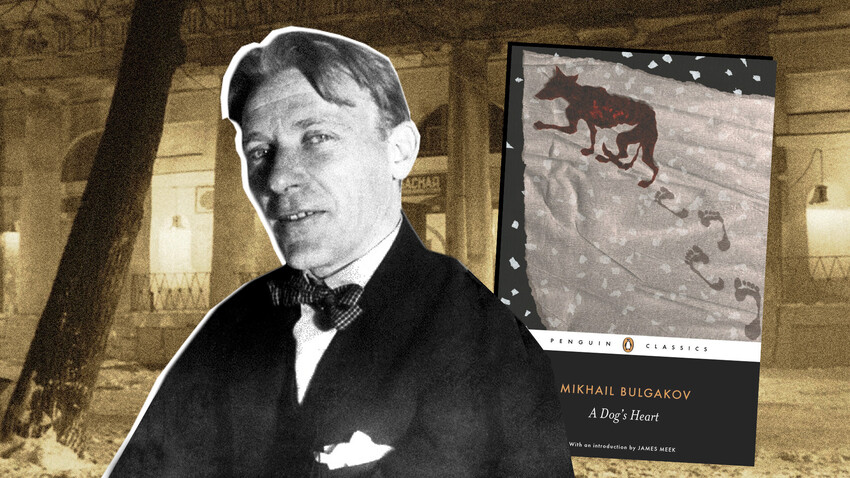

This story has elements of sci-fi, political and social satire and medical humor. The author himself was a doctor, so his early creative writing was mostly devoted to medical issues (like ‘The Young Doctor’s Notebook’, which turned into a 2012 British TV show starring Daniel Radcliffe and Jon Hamm).

Professor Preobrazhenksy had a real life prototype in Bulgakov’s uncle, Moscow professor Nikolai Pokrovsky. He inspired Bulgakov to become a doctor, he had a lot of traits that his literary alter ago did and his real apartment looked exactly like the one described in the novella.

Besides from the intriguing plot with fantastical and sci-fi elements, very rare for to those times, ‘Heart of a Dog’ is a sharp satire on the Soviet political and social life order. It shows a huge the contradiction between the old intelligentsia and the new proletariat, which gained absolute power at once (sometimes with little education, but able to demagogue with political slogans they learned).

Professor Preobrazhensky’s critical phrases about the Bolsheviks and their new rules became aphorisms, very often quoted by Russians to this day. Below are some of the most recognized:

‘Heart of a Dog’ was written in 1925, but not a single literary magazine or publishing house would touch it. “It's a poignant pamphlet on modernity and could never to be printed,” the censorship indisputably reacted.

However, the manuscript of the novella did circulate via ‘samizdat’. People printed self-published copies and passed from hand to hand. As a result, in the 1960s, one of the copies (with many mistakes) reached the West and was published there.

In the USSR, the work only saw the light during perestroika and era of glasnost. In 1987, it was published in the ‘Znamya’ magazine. And finally reaching a wide audience, it made a splash. People remembered how, reading it in one sitting, they were shocked at how great it was (and many said they actually were reading such Soviet satire for the first time).

Almost immediately, in 1988, the book was adapted to the screen and the resulting movie directed by Vladimir Bortko is still considered one of the greatest Soviet movies ever and one of the best adaptations of a literary work.

Check out it with English subtitles here.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox