A still from ‘Battalions Ask for Fire’ movie based on Yuri Bondarev's novel

Vladimir Chebotaryov, Alexander Bogolyubov/Mosfilm, 1985Russian literature has a rich tradition of military prose, because many writers of the 19th century were in military service. Moreover, one of the oldest works of Russian literature, ‘The Tale of Igor's Campaign’, tells about an unsuccessful military campaign of the Russian army against the Polovtsians (aka Cumans or Kipchaks) in the late 12th century.

Much later, works such as ‘Sevastopol Stories’ by Leo Tolstoy appeared. The writer was in military service and described the events of the defence of Sevastopol in 1855, which he witnessed with his own eyes. He is considered the first war correspondent and the founder of the so-called ‘lieutenant prose’. He spoke unvarnished about military actions, immersing the reader in the thick of events, described how the front looked like, how the city was after the hostilities, how the wounded suffered. His main message was the senselessness of war.

Leo Tolstoy in uniform of a participant of the Crimean War, 1856

Public domainCritics believe that if not for this life and literary experience, Tolstoy would not have been able to describe the front scenes of ‘War and Peace’ so masterfully.

Later, Leonid Andreyev wrote a very strong modernist story titled ‘Red Laughter’ about the horrors of the Russo-Japanese war.

But, such a concept as ‘lieutenant prose’ was first talked about after World War II (or the Great Patriotic War, as Russians call it). This was both due to its scale, which affected every Soviet family, and to the fact that it was first war where most of the participants were literate. Almost everyone wrote letters to their relatives and could leave evidence of their experiences.

Literary scholars still argue about the origin of the term, sometimes attributing the authorship to writers (Yuri Bondarev or Viktor Astafiev) or critics (e.g., Igor Vinogradov).

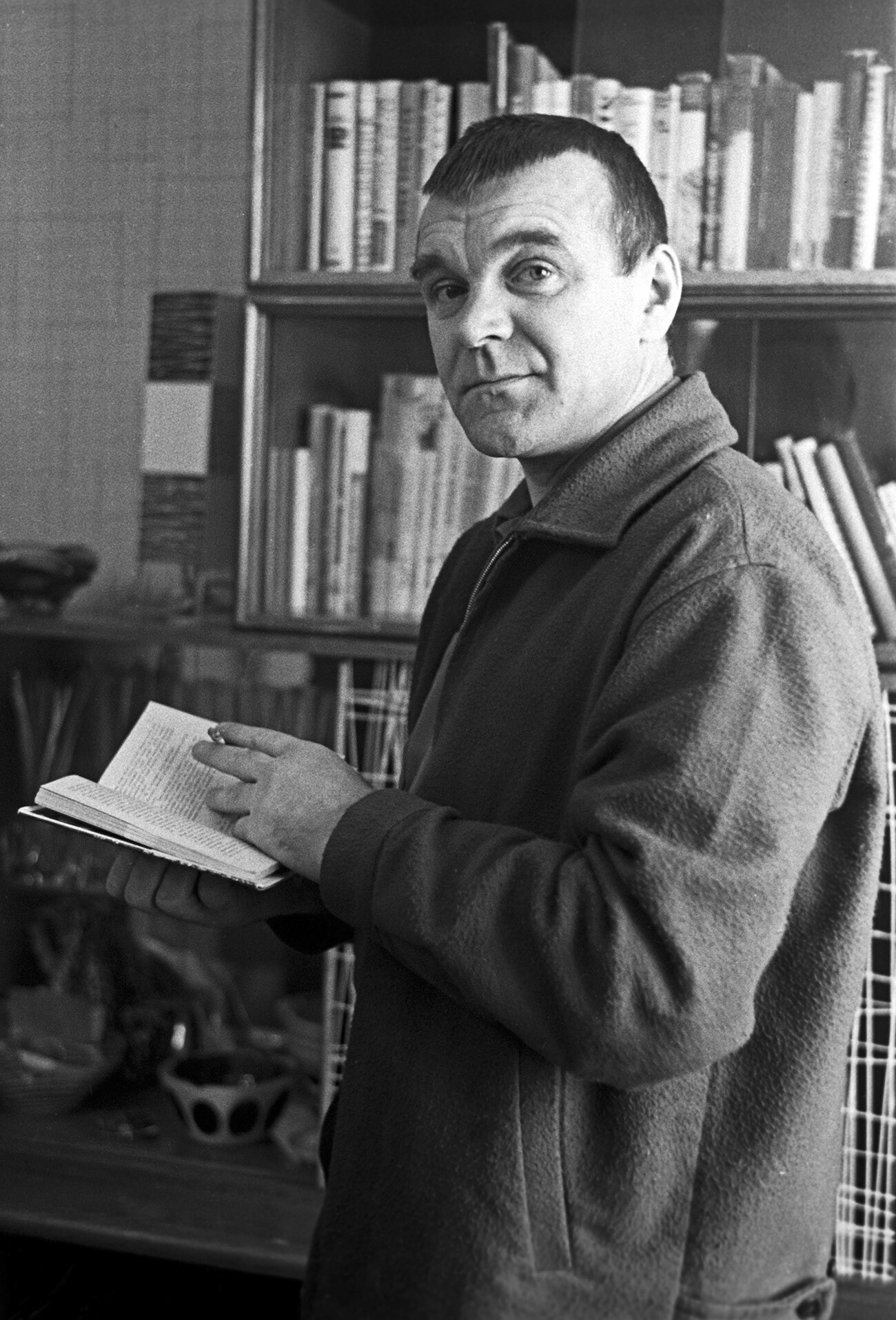

Soviet writer Yury Bondarev

Lev Ivanov/SputnikAfter the Victory, many people left their memoirs, from Marshal Zhukov and famous writers like Konstantin Simonov to junior officers. Sometimes, these ingenuous and far from highly artistic works brought the reader stronger emotions than the creations of professional writers.

As opposed to varnishing the war and depicting exclusively the triumph of the victorious nation, the lieutenants wrote about both the difficult “trench” moments, as well as the joys found even during the war.

“We were not afraid of tragedies, we wrote about a man who found himself in the most inhumane situation. We looked for the strength to overcome himself in him and, in hard times, we looked for good and tried to see the future. We depicted the war as we saw it ourselves, as it was,” noted Yuri Bondarev, one of the brightest representatives of the ‘lieutenant prose’.

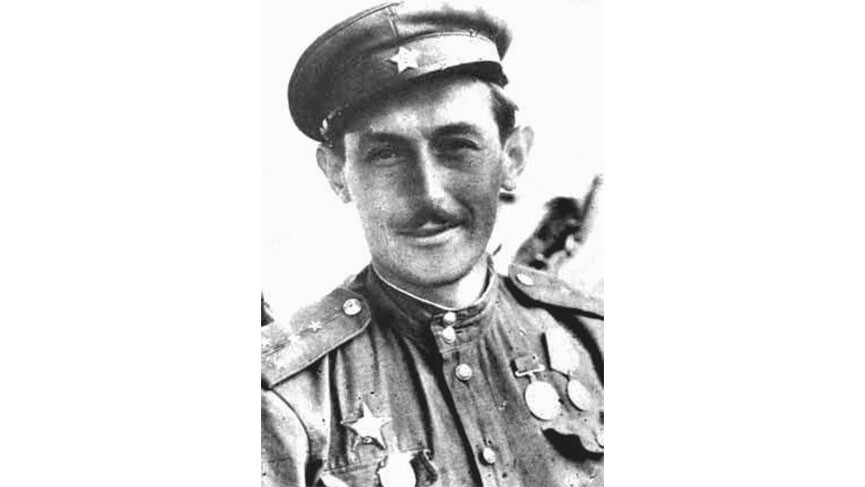

Viktor Nekrasov in 1945

Public domainRight after the war, Viktor Nekrasov's novella ‘Front-line Stalingrad’ (literally ‘In the Trenches of Stalingrad’) resounded loudly. It was after this work that people started talking about ‘lieutenant prose’, which demonstrates the “trench truth”. Many writers praised the work and especially its proximity to real events. The story, published in the ‘Znamaya’ literary magazine, was read by Joseph Stalin personally, after which the author received the Stalin Prize.

A still from “Soldiers”, film adaptation of “Front-line Stalingrad” by Viktor Nekrasov

Alexander Ivanov/Lenfilm, 1956However, soon, the authorities began to fear that too much “truthful” evidence could have a detrimental effect on the heroization of Soviet front line soldiers and, in general, the role of the USSR and Stalin in the war and victory. Therefore, the already published works were put away in a special storage and new ones were no longer allowed to be published.

It was only during the Khrushchev Thaw that more opportunities arose for the publication of new unvarnished testimonies (Although there were exceptions, and, for example, Vasily Grossman's epic ‘Life and Fate’ was banned).

Vasyl Bykov in his house in Minsk

Yevgeny Koktysh/SputnikOther bright representatives of ‘lieutenant prose’, in addition to Nekrasov, were:

A still from 'At War as at War' by Vladimir Kurochkin's novel

Viktor Tregubovich/Lenfilm, 1968Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox